Awaiting a puff of moon dust

In the predawn hours Friday, while those on the West Coast still snooze, a rocket is scheduled to punch a 13-foot-deep hole in a crater at the moon’s south pole that hasn’t seen sunlight in billions of years. The purpose: to find out whether ice lies hidden there.

NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, which set out for the moon in June, made a late-course correction Tuesday to better position itself to steer the rocket into the 2-mile-deep crater Cabeus at 4:30 a.m. PDT on Friday.

Four minutes later, if all goes according to plan, the spacecraft will fly through the cloud of debris that will rise above the lunar surface and linger there briefly. As it passes through the cloud, the satellite’s nine instruments will analyze the dust and debris for evidence of water, before crashing itself.

Back on Earth, amateur astronomers from Colorado to Silicon Valley are expected to turn their telescopes to the celestial show, even though it will last less than a minute.

Scientists preparing for the collision could hardly contain their excitement over what might turn up in that short time.

“The spacecraft is looking great. I don’t think we could miss the moon now if we tried,” said Steve Hixson, vice president of Advanced Concepts at Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, which built the craft.

“It’s our job to confirm there is water there,” said Dan Andrews, the project manager at Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif., which designed the spacecraft instruments. “But even if it’s very dry, that’s a good answer to have.”

The LCROSS satellite was originally a $79-million add-on to the larger, $500-million Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, whose mission is to map the moon. But the theatrical nature of the impact event has caught the public’s attention.

Thousands are expected to show up Thursday night at the Ames complex south of San Francisco for an evening of music and movies that will culminate with a live video feed of the impact.

“It’s kind of hard to keep on top of how much interest there is out there,” Andrews said. “I’ve heard 10,000 are coming.”

1999 discovery

For decades after the Apollo missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s, scientists considered the moon to be little more than a dry wasteland.

But in 1999, NASA’s Lunar Prospector mission found evidence of hydrogen, a possible indicator of water, in permanently shadowed craters at both poles. Since then, other spacecraft have detected the same thing, leading scientists to wonder whether large stores of ice billions of years old are hidden in craters that never get sunlight.

According to scientists, water on the moon would be as valuable as gold. Not only would it be useful to drink, should President Obama continue former President George W. Bush’s ambitious plan to build a lunar base there after 2020, but it could be broken down to make breathable air and even rocket fuel.

Transporting water to the moon, on the other hand, would cost $50,000 a pound.

The crater-observing satellite launched June 18 attached to a second spacecraft, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Shortly after launch, the two separated.

The orbiter continued on to begin a yearlong mission to map the moon in search of landing sites for future lunar colonists.

The sensing satellite went into a long, looping orbit around the Earth to line itself up for Friday’s impact.

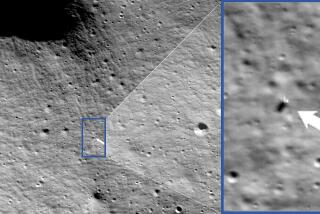

Originally, spacecraft controllers had chosen a nearby crater, Cabeus A, as the target. But last week, they decided it wasn’t as good a potential source for water as Cabeus, a 60-mile-wide valley near the moon’s south pole.

Andrews said satellite controllers were aiming for a spot in the northwest region of the crater, where temperatures of minus 397 degrees Fahrenheit would ensure that any water would be frozen as hard as rock.

The Centaur rocket that will hit the crater is the upper stage of the Atlas V that launched both spacecraft in June. Having used its fuel, it is now a 5,200-pound projectile.

About 10 hours before Friday’s impact, the rocket will separate from the satellite and head directly for the crater.

Meanwhile, the satellite will maneuver itself into position to fly through the debris kicked up when the rocket crashes.

According to NASA, the rocket will be traveling about 5,600 miles per hour when it plunges into Cabeus. That will create a dust cloud rising as much as six miles above the lunar surface, providing a rare show for amateur astronomers with telescopes 10 inches or larger.

The collision can theoretically be seen throughout the Southwest and as far away as Hawaii, providing the observer has a large enough telescope at hand and good viewing conditions.

Mountaintops and valleys with little or no ambient artificial light are the best places to go. Because the debris cloud is expected to last less than a minute before settling back down on the lunar surface, viewers need to be punctual and have sharp eyes.

Palmdale gathering

Locally, the Antelope Valley Astronomy Club is hosting a viewing party at the Sage Planetarium at Cactus Intermediate School in Palmdale.

Members will set up telescopes outside, while NASA’s broadcast of the event will be shown inside.

Scientists think the lunar water, if it’s there, arrived the same way it did on Earth: through billions of years of bombardment by water-rich comets and meteors.

Any water that was deposited in sunlit places would quickly be lost to the moon’s scorching daytime heat, which can reach 250 degrees Fahrenheit. But in shadowed craters, the water could remain as ice for eons.

Bernard Foing, the project scientist for the European Smart-1 spacecraft that took pictures of the crater several years ago, said the floor of Cabeus contained a number of small craters that appeared old enough to have trapped water from comets and water-rich asteroids.

Andrews said it could be days or weeks after the impact before scientists conclude that there is, or is not, water at the pole. Besides the crater-observing spacecraft, observatories around the world will be watching, along with the Hubble Space Telescope and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

If the satellite doesn’t find water, that wouldn’t be definitive proof it’s not there. Besides mapping instruments, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter carries instruments that can search for evidence of water as it skims 30 miles above the lunar surface in the coming months.

Several weeks ago, research teams reported evidence that tiny amounts of water exist on the surface in some areas of the moon. But that is likely too little to be of practical use for future colonists.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.