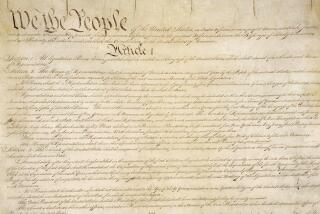

Happy Constitution Day! Take an amendment to lunch

Happy Constitution Day, commemorating when a group of Founding Fathers 227 years ago signed the new document, later ratified as the nation’s blueprint. The U.S. Constitution became a template for constitutions around the world because it defined duties and responsibilities among the branches of the national government and the government’s relationship with the states. The battles of that era remain surprisingly vibrant in today’s political world.

Why was the Constitution written?

The short answer is that the previous document, formally known as the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, worked for the 13 states fighting a revolution against England. But when it came time to actually govern, it was too weak. The Articles created a confederation, but not a real government. For example, there was no president, no executive agencies, no judiciary and no tax base. Getting anything done, from putting down internal rebellions (yes, there were rebellions against the new United States including the famous Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts) to establishing a national currency for commerce, or even paying off war debts, were all impossible.

Did everyone agree that a Constitution was needed?

Most of the intelligentsia agreed something had to be done, but even back then the essential tension between local versus national control was apparent, a political fight that continues to this day. The Constitution defines powers among the branches of national government -- executive, Congress, courts -- but that fight is also far from resolved. The nation split into two camps, the Federalists, who supported a stronger national government whose powers were divided, and the anti-Federalist camp, including prominent patriots such as Patrick Henry of “Give me liberty or give me death!” fame.

Why did the Federalists triumph?

There are many reasons, but essentially the anti-Federalists never came up with a plan for the essential needs of a growing nation: money and security. They were successful, however, in sounding a fierce call for personal freedom, dislike of central authority and fear that the government would revert to a monarchy, but at the end of the day the anti-Federalists couldn’t compete. The Federalists also had an advantage: one of the first uses of propaganda, in the form of the Federalist Papers, the brilliant series of 85 essays that explained the new government and served as op-ed pieces to sell the nation on the value of a strong government.

So after the final ratification by Rhode Island in 1790, everyone was on board?

Not so much. The underlying political problems over national versus the states and executive versus the Congress, had been papered over but hardly resolved, and both revolved around slavery. First, delegates agreed to split legislative power between one House based on population and a Senate based on the same number of lawmakers, picked by the states without regard to size. In this way small and large states had equal theoretical power. Then came the question of how to count slaves, who were property and couldn’t vote. This too was compromised so that a slave counted three-fifths of a free man (women were not part of anyone’s calculus at the time). This meant that slaveholding states in the South would have more legislative influence. In the process, slavery as an institution would continue to be allowed despite the calls for freedom and abolition. As the famous abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, proclaimed at a July Fourth rally in 1854 as he set the document ablaze: “The United States Constitution is a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.”

But after the Civil War, everything calmed down, right?

Again, not so much. The Constitution was written when the United States was an agrarian society with a limited homogeneous political class that kept power through a limited electorate. Lying ahead were battles over industrialization, unionization, race and social issues from civil rights, women’s rights, abortion and even to who shall be allowed to marry. All are ideas that have been fought on constitutional grounds, as have numerous questions of what exact powers the different levels and parts of government can have. All of the issues at their heart deal with the broad question of citizenship.

In 1952, Congress created Citizenship Day and moved it to Sept. 17, the anniversary of the Constitution’s signing. By 2004, Sen. Robert C. Byrd (D-W. Va.) got an amendment passed changing the name of Sept. 17 to Constitution Day.

Byrd was famous for many things, including carrying around a pocket copy of the Constitution.

Follow @latimesmuskal for national news

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.