Campaign spending explodes: A look at where the money has gone

Center for Responsive Politics

The U.S. Supreme Court moved this week to loosen limitations on big political donors, continuing a march that has contributed to an explosion of campaign spending.

Consider the shift over a mere 20 years: as 1992’s presidential campaign dawned, Bill Clinton was considered a master fundraiser because he had pulled in just over $3 million the previous year.

By 2012, President Obama and his Republican nemesis, Mitt Romney, each corralled more than $1 billion in donations. And that’s just counting money their campaigns raised, not hundreds of millions of dollars more in outside, legally independent spending.

Some of the growth comes from inflation, some from population increases over time. But much of the dramatic surge in fundraising and spending in recent years stems from court decisions that have relaxed restrictions in campaign spending enforced since the Watergate era.

The high court on Wednesday effectively moved the maximum amount a single donor can offer candidates running for Congress from $123,200 per election cycle to $3.6 million. It did that by voiding the limit on the amount of overall money that one donor can give. It left in place the current restrictions against giving more than $5,200 to any single candidate, though the language in the decision suggested that the per-candidate rule’s shelf life may be coming to an end as well.

The decision built on the court’s ruling four years ago in the Citizens United case, which freed corporations, unions and others to spend unlimited amounts on campaign efforts through so-called super PACs. Those groups and their fundraising brethren, tax-exempt social advocacy groups that do not have to report their donors, spent about as much in the last election season as each presidential candidate.

The Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks campaign donations and spending, compiled data from finance reports and what can be discerned from the newer sorts of groups—at least those which make public their donors.

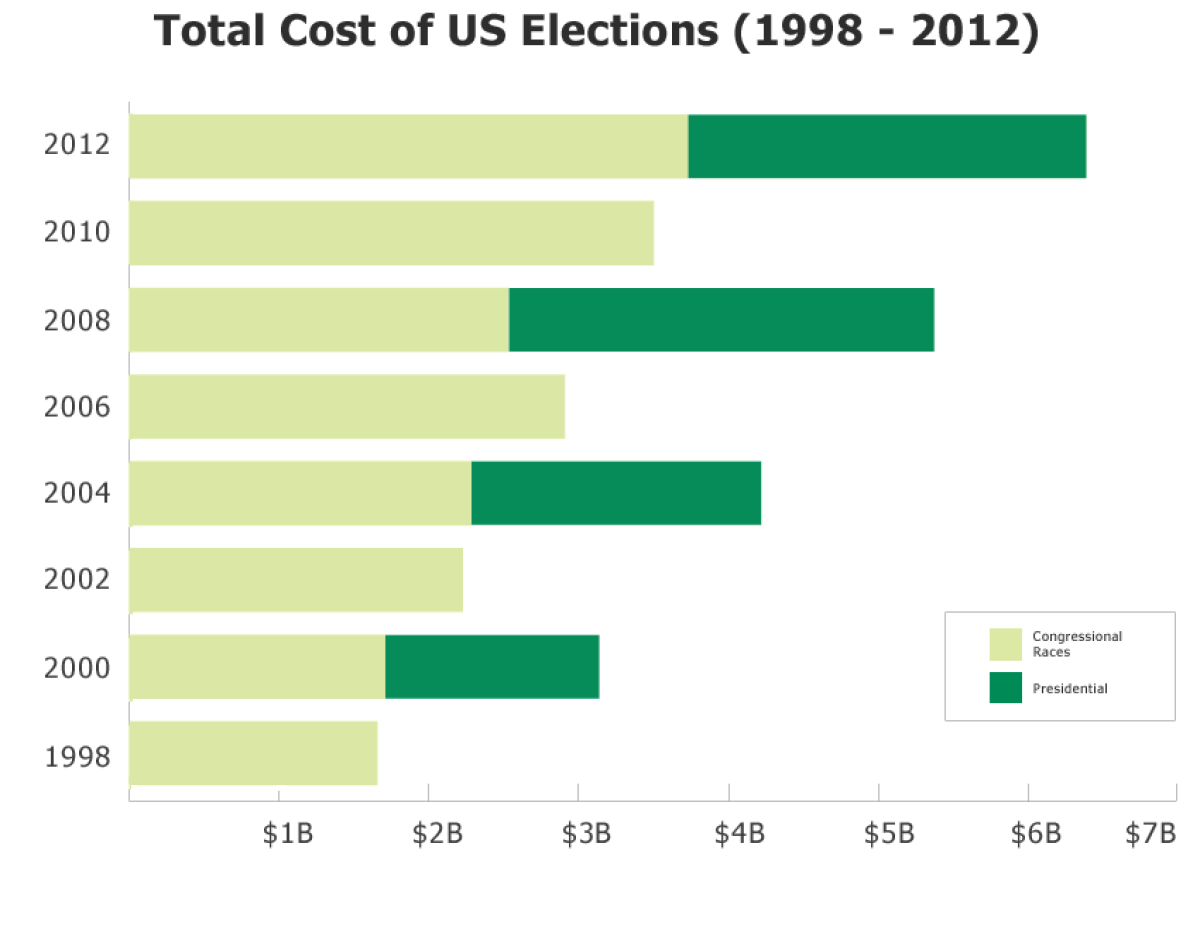

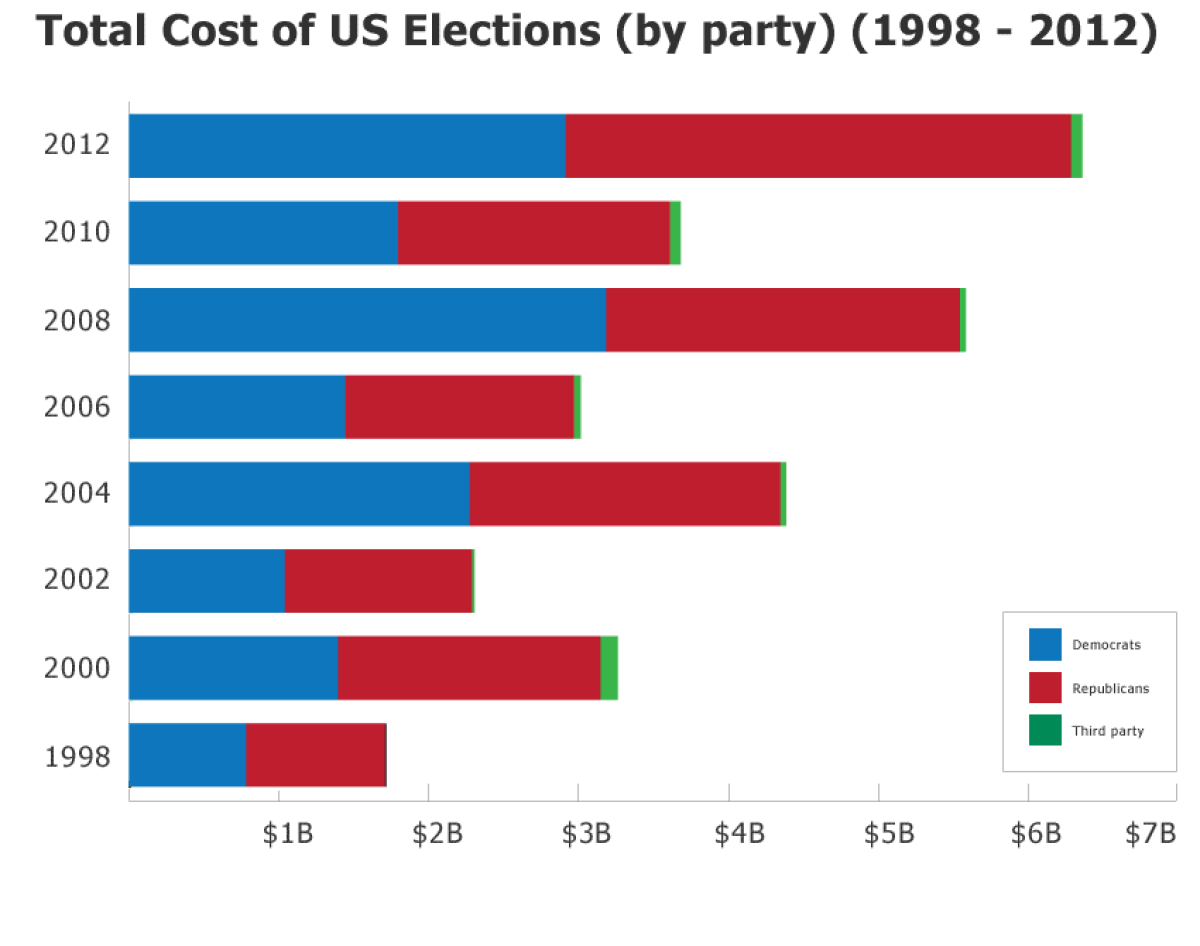

In the hotly contested presidential year of 2000, it found, the total election bill for White House and congressional candidates was less than $3.1 billion. By 2012, the cost had more than doubled to nearly $6.3 billion. Among congressional races—the kind likely to be even better financed under the terms of the new court decision—the cost rose from less than $1.7 billion to almost $3.7 billion. Republicans outraised Democrats, with 52% of the 2012 spending, to 44% for Democrats.

Center for Responsive Politics

In the wake of the Supreme Court decision, opinions abounded about its impact.

Some analysts suggested that because only a few hundred donors nationally bumped against the smaller spending limit, only that small number were likely to further empty their wallets under the new, looser rules. Some suggested that it was more likely that money would shift from the surreptitious accounts encouraged by the Citizens United decision into more direct—and public—campaign accounts run by candidates and parties.

One thing has been abundantly clear in the last few decades: Whatever the rules, money will find its way into the system in ever larger sums.

cathleen.decker@latimes.com

Twitter: @cathleendecker

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.