In his own right

William F. Buckley Jr., as anybody who has seen the great Buckley impressions by Joe Flaherty or Robin Williams can attest, was hardly inimitable. But the contributions of the National Review founder and long-serving icon of conservatism extended far beyond his personal style and charisma. Buckley, who died Wednesday at 82, was a major figure in shaping not only contemporary conservatism but the contemporary United States -- though in neither case would he have fully countenanced the results of his labors.

When National Review debuted in 1955, “conservative intellectual” was considered an oxymoron, and Buckley was not off-base when he claimed that historian Richard Hofstadter “analyzed” liberals but “diagnosed” conservatives. The National Review of the ‘50s and early ‘60s not only reversed that trend but had a fair claim to being the foremost cultural magazine of its time. If conservatives have outpaced liberals in recent decades as generators of new ideas, Buckley deserves much of the credit.

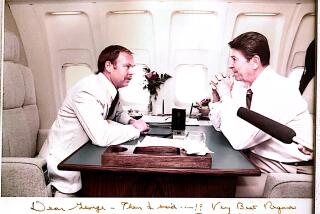

It was an irony of Buckley’s career that after he boosted so many Republican presidents, they invariably disappointed him. Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air Act and imposed wage and price controls; Ronald Reagan left office with the Department of Education intact; George W. Bush vastly increased Medicare benefits and plunged the country into a war that Buckley turned against long before that became an acceptable conservative position. (Also to his credit, Buckley emerged in the 1980s as an opponent of the war on drugs.)

Buckley himself was not immune to the contradictions in what used to be called conservative “fusionism.” Having largely purged the movement of its libertarian extremes, National Review grew comfortable with executive power, social engineering through tax policy and other ideas at odds with certain tenets of conservative ideology.

But today’s conservative identity crisis is a function of the movement’s success, and Buckley’s combination of courtly manners and a madcap sense of humor (two qualities the current, generally more shrill generation of conservative pundits might want to emulate) helped make that success possible -- sugarcoating seemingly strange and inaccessible ideas until they became commonplace. Liberals and conservatives alike owe him a debt of gratitude for bringing a new intellectual rigor to political discourse.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.