African Catholics Seek a Voice to Match Their Growing Strength

LAGOS, Nigeria — A fierce competition for souls is on in Lagos. In this sprawling capital that seems glued together out of scraps of rusted iron, plywood and torn posters, the immortal combat is being waged on faded billboards so closely planted along the highway that it’s difficult to make them out as they flash by: Divine Harvest! Holy Fire! Winners Chapel! Victorious Family! Champions Chapel! Miracle Explosion!

None of the posters is for the Roman Catholic Church, which is growing faster in Africa than anywhere else. Father George Ehusani, secretary-general of the Catholic Secretariat of Nigeria, hardly needs to advertise, when the church’s biggest challenge is not attracting people but dealing with the growth.

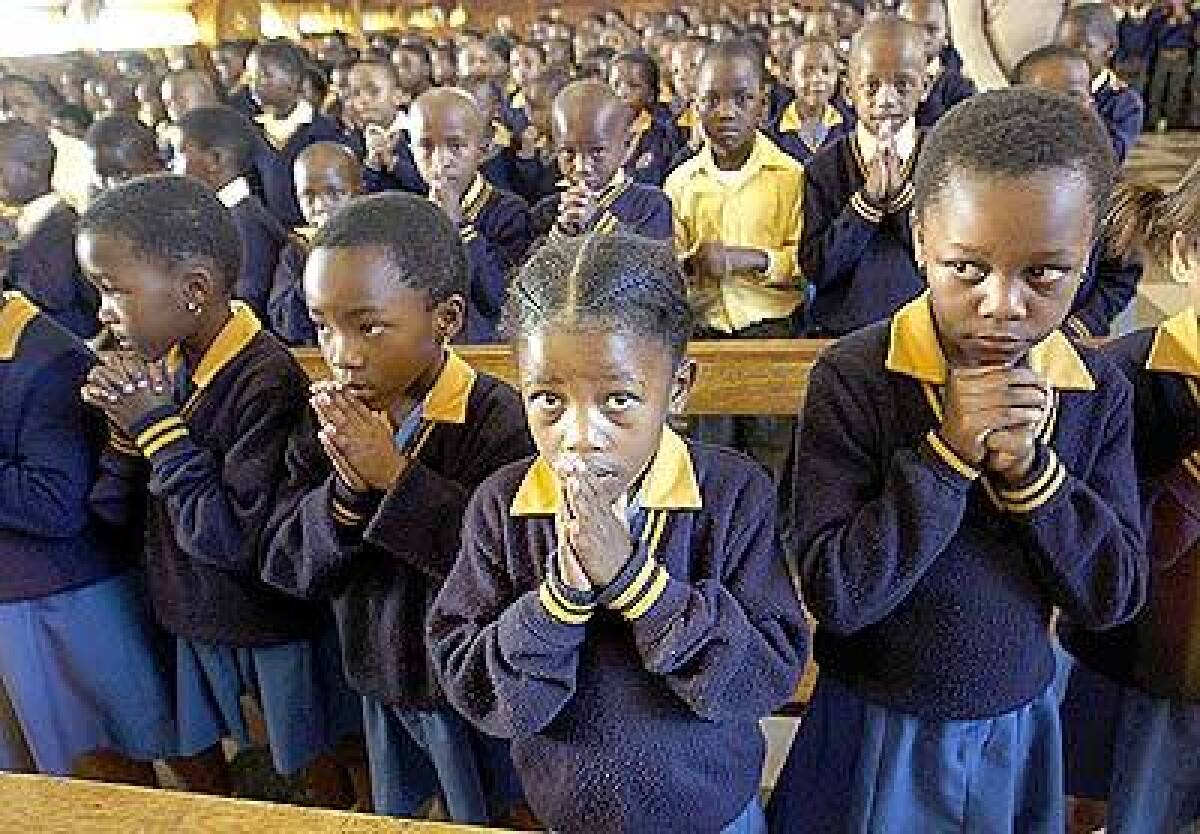

The number of African Catholics has increased 30% in a decade, to more than 130 million, served by 426 bishops and more than 27,000 priests. In Nigeria, with about 25 million Catholics in a population of about 137 million, congregations spill out onto benches outside most Catholic, churches, even with five or six Masses on Sundays.

The phenomenal growth brings ambitions, and not only for an African pope when the College of Cardinals convenes next week. Catholics here are also eager to dispatch a wave of African priests, generally conservative, to an increasingly secular Europe and United States, just as white missionaries once arrived on African shores.

Their time, these Africans believe, has come.

But the growth, attributed to high birthrates and Irish missionaries’ proselytizing in schools, is also creating problems. Thinly stretched priests are barely able to serve their own congregation’s needs, leading some neglected Catholics to turn instead to the less restrictive — and even faster-growing — evangelical Protestant churches.

Catholic clerics also face cultural pressures from those rival churches, where no preacher will get upset when a worshiper shouts out hallelujahs, sings, dances or drums any time they feel moved by the Holy Spirit.

Ehusani acknowledges that growth hasn’t come without difficulties.

“You go to Catholic churches in this country and they’re all overfull. If you are five or 10 minutes late, you will hardly find a seat,” he said. “Some are not happy that there’s not enough dancing and there’s not enough miracles, and they move on. But their seats are taken by others.”

But, he admitted: “You can have some problems with quality when you have large numbers. Some of the needs that the Pentecostal preachers are meeting, we have not been able to meet, and I humbly admit that.”

With thousands of people being confirmed into the faith, Ehusani said, priests can’t hope to interview each one. And with thousands of followers in each parish, there is no hope of visiting each sick and dying person, as many believers expect.

Father Innocent Opogah serves a parish of 4,000 people at Badagri, about 30 miles west of Lagos. The 30-year-old struggles to handle his duties, which include ministering to 13 distant villages.

One of his most difficult jobs, he said, is to make people understand the limits of incorporating traditional African culture into the church.

Since the late 1960s and ‘70s, there has been a move to make a place for local language, drums, tambourines and traditional costumes, a process the church calls inculturation.

“Trying to explain inculturation to the people is not very easy,” Opogah said. “As Africans, we love to sing. Now this has been accepted. We can sing, dance, beat drums. But these are checked.

“Some say, ‘The Holy Spirit moved me to sing at this time.’ That is where it is difficult to explain to the people that at certain times you can’t do certain things. With burials, some say, ‘We want to open the coffin and dance around it and sing.’ We say, ‘No, no, no, we don’t do that in the Catholic Mass.’ Things like that we reject. Maybe that is why the church is seen as being too strict.”

Eleven of the 115 cardinals who will choose the next pope are from Africa. Nigerians, even Muslims, fervently hope that Cardinal Francis Arinze, born of non-Christian parents in a mud house in the Nigerian village of Eziowelle, will be elevated to the papacy. Arinze is a conservative who argues that politicians who support abortion and homosexual rights must be denied Holy Communion.

But at least three Catholic leaders in Africa — Archbishop Theodore Adrien Sarr of Dakar, Senegal, Archbishop Buti Tlhagale of Johannesburg, South Africa and Cardinal Bernard Agre of Abidjan, Ivory Coast — say they believe it is unlikely that an African will be chosen to be the new pope.

Tlhagale has said the Vatican is like a train that cannot make sharp turns, and that though the cardinals were happy to have many Catholics in Africa, “they don’t think we are ready for high positions. They fear paganism might come through the back door.”

But across the faiths, Africans are tired of waiting.

One recent sweltering evening, in his plywood shack of a church in Owode Ajegunle on the outskirts of Lagos, a young Pentecostal evangelist, Pastor Steve Ahanotu, boomed his own message into his microphone before a swaying congregation.

“This is the time of the African,” he declared, as overhead fans decked with curling ribbons swirled. “The Europeans have had their time, the Asians have had their time, the Americans have had their time. The black man is going to read the last Gospel before the coming of Christ. That is why the most vibrant churches in the world are pastored by blacks. It’s our time.”

Ahanotu, 39, encapsulates the hurtling journey through faith that many African families have made. He was raised a Catholic by his mother, who practiced it along with traditional African beliefs.

But the rosaries, the confessions, the coming and going to church while banking on old beliefs seemed too half-hearted to Ahanotu. At 17, he embraced the Redeemed Evangelical Mission, which meant he had rejected all the African spiritual traditions his father taught.

“My father expressed his displeasure. He said, ‘I don’t like you going to that church. You’re going to get lost.’ I just had to go my own way.”

His father never abandoned his traditional faith, so the pastor lives with the painful conviction that he will not enter heaven.

At the end of Ahanotu’s evening prayer meeting, Teresa Isichei stepped forward, complaining of a headache. The pastor put his hands tightly on her head, prayed for several minutes and told her she was healed. Indeed, she said, the headache was gone.

“The prayer is different to the Catholic Church,” said Isichei, who grew up Catholic. “See how he prayed now? We used to say ‘Hail Mary, full of grace,’ but I feel as if this prayer is more powerful. If a person is sick, it can heal them.

“This church is better than the Catholic Church,” she said, though she still calls herself a Catholic.

Some African Catholics believe that an African pope would keep Catholics from gravitating to the evangelical churches as well as send a powerful message to the world that all people are created equal.

“It would make a vibrant church even more vibrant,” said Ehusani, of the Catholic Secretariat.

But even if an African is not selected to lead the church, many Catholics believe that African priests are ready to lead Catholics in Europe and the United States back to the moral absolutes of the church, to preach the need to eschew contraception, avoid adultery and reject homosexuality as evil.

AIDS activists have criticized the Catholic Church’s strong campaign in Africa against the use of condoms as a means of checking the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus, which causes AIDS.

And some doubt whether the conservative message that most African Catholic priests offer is capable of answering the needs of Catholics in developed Western countries.

“It’s very perplexing when there are people arguing in the West, ‘No, we don’t want African priests, let them take care of themselves,’ ” Ehusani said. “It’s a poverty of the mind.”

Issues such as the use of condoms, premarital sex and homosexuality are moral absolutes that can never be determined by popular opinion, he said.

“What is happening is a crisis of faith. There’s a widespread loss of a sense of moral absolutes,” he said.

“In Europe and America, people may be afraid of what they see as our conservative Christian views. But what I see is a matter of an attempt to reduce Christianity to an opinion poll.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.