Talking through the pain

Folsom, Calif. — IT’S a warm, cloudless day and Patty O’Reilly is about to meet the man who killed her husband. A million thoughts compete for attention in her head. Two stand out.

Why am I here?

What good will it do?

It has taken O’Reilly 29 months to get to this emotional state, to the point where she can walk on sturdy legs into a maximum-security prison and face a convict who blasted a giant crater in her life.

In the beginning, O’Reilly felt only loathing for the man. She was too wracked by loss to consider anything else.

But gradually she became aware of the possibility, however slight, of finding some useful purpose in her grief. That’s why she is here today, in the belly of the state prison at Folsom, with a water bottle, rosary beads and her sister at her side.

Soon a door will swing open, and inmate No. T22186, a man named Mike Albertson, will appear in his prison blues. The two will sit face to face — victim and victimizer — and talk. What comes out of it is up to them.

The encounter is a first for the California correctional system. Minnesota, Texas and other states have encouraged such dialogues, but California — its prisons beset by overcrowding and countless other woes — is arriving late to the game.

O’Reilly, a petite, dark-haired woman of 41, is a willing pioneer. Through her sorrow, she has become a believer in restorative justice, the philosophy underlying her meeting today. To heal, she says, survivors of crime need something beyond the punishments the courts dispense: the chance to hear the truth about what happened to their loved ones and “the empowering opportunity” to look the offender in the eye.

The goal for offenders, meanwhile, is a flesh-and-blood understanding of the harm they have caused.

“When you put a real face on the crime and hold them accountable, there’s no escaping the impact,” says Rochelle Edwards, a mediator from the state’s Office of Victim and Survivor Services. Then, she adds, convicts “connect the dots in their own lives” to learn what set them on a criminal path.

“After that, they can’t go back,” she says. “They have too many insights, too many tools, to offend again.”

O’Reilly’s trust in the process is strong. But on this September morning, she has no real idea what lies ahead.

Nor does Albertson, 49, the unwelcome intruder in O’Reilly’s life. He has spent months awaiting this day. Abandoned by family and friends, he has had no visitors since he was sent to prison in September 2004. His health is poor, and his remaining 12 years behind bars stretch before him.

What good will come from revisiting this crime? What can he possibly say or do to make amends?

“I used to think a great deal of myself, before all this,” Albertson says. “And now I am a person who has done something unimaginable, something so heinous. The pain, fear, sadness and guilt surrounding that are just overwhelming sometimes.”

THE event that knit these lives together happened on a spring evening in 2004, in the heart of Northern California’s wine country. Riding his bicycle home from work, Danny O’Reilly was struck from behind by a pickup truck. In an instant, his life ended at 43.

At first, his widow felt she could not go on. Only the needs of her two children, themselves overcome with grief, kept her trudging forward.

Eventually, she resumed work as director of a dance studio and struggled to reassemble her life. Albertson, who had been driving drunk, pleaded guilty to manslaughter and received a prison term of 14 years. But Patty O’Reilly came to crave a different sort of justice, a more direct expression of accountability from the man who had altered her world.

Two years later, her day begins early, at the modest home in Sonoma she shares with daughters Erin, 15, and Siobhan, 10. After a long drive, she and her sister, Mary Eble, arrive at the prison east of Sacramento. Edwards is with them.

For months Edwards has been preparing O’Reilly and Albertson for their meeting — unearthing possible land mines, suggesting how both might find meaning in their unexpected relationship. Today, she will guide the conversation, provide support. “A human guardrail,” she calls herself.

The warden meets the trio at the prison gate, offering his welcome and a warm handshake. At the first security stop, officers search the visitors’ belongings, almost apologetically. Word of O’Reilly’s purpose here has spread.

O’Reilly removes her white tennis shoes and crosses through the metal detector. After a short van ride, and two more security checks, the three women arrive at their destination, a small, windowless conference room. The lights are bright, and Edwards does not like the feel of the place, pronouncing it cramped. But it is a prison, and there are no options.

O’Reilly sits in one of five chairs around the table’s edge. Four water bottles are lined up near her, beside a box of tissue. She takes a bite of an apple, then rests her head on both hands and takes three deep, audible breaths.

A low rumble and the clank of doors signal a possible arrival, but it’s a false alarm. As the wait drags on, O’Reilly thumbs through a folder of family photos with her sister and begins to cry.

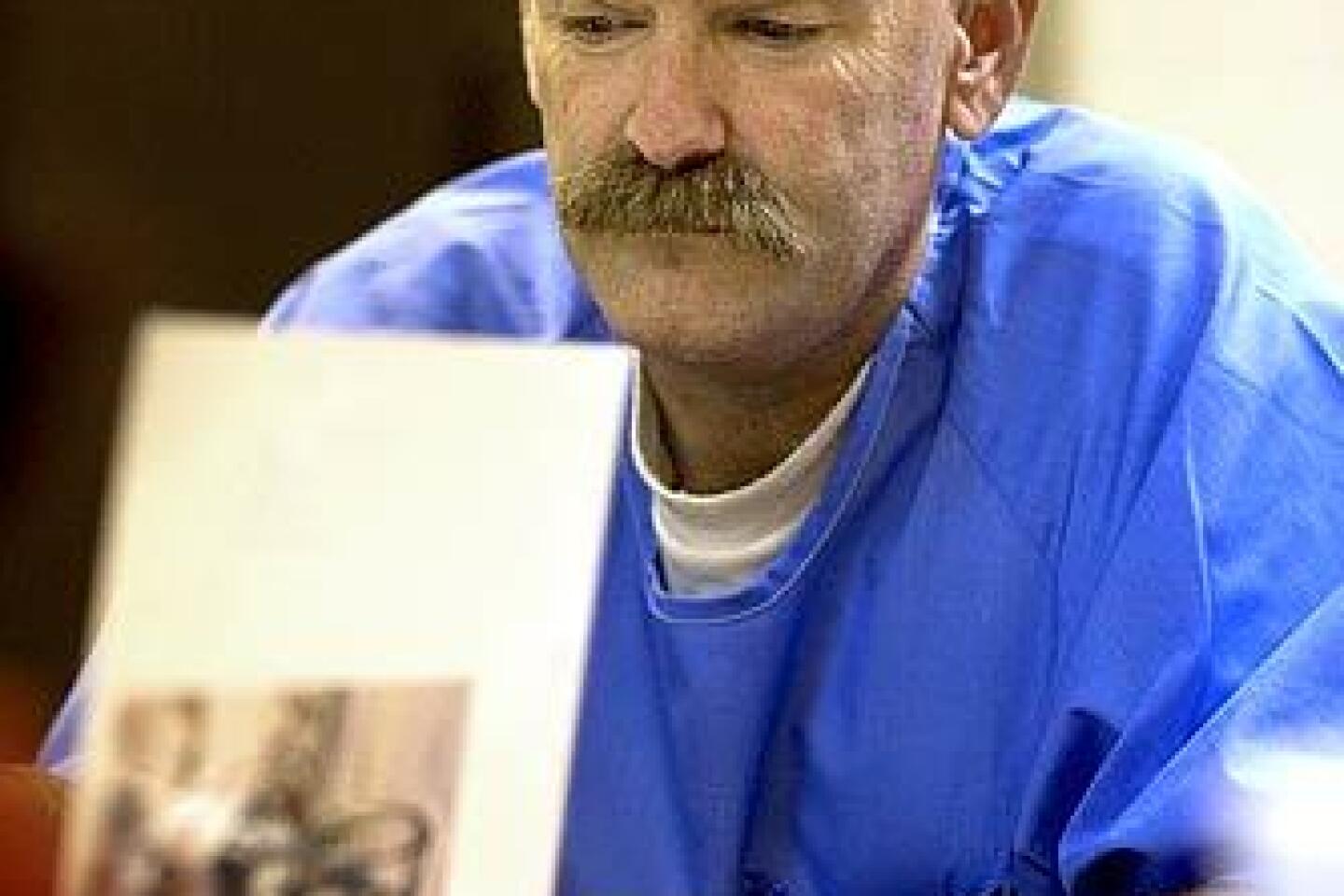

Finally, an officer escorts Albertson in and sits beside him at the table. O’Reilly searches the convict’s worn face. Albertson, whose graying brown hair is cropped short, swallows hard and nods a nervous hello.

“Let’s take one minute to bring ourselves here,” Edwards says, her calm voice a small ripple in the still pond.

O’Reilly bows her head and prays.

Gently, Edwards sets the dialogue in motion, establishing ground rules. There is no interrupting — if you want to say something, write it down so you don’t forget — and no abusive language allowed.

O’Reilly fixes a level gaze on Albertson and tells him it is her younger daughter who prompted her to come. The child expressed curiosity about the man who killed her father; thus was born O’Reilly’s interest in restorative justice and the healing it might bring.

O’Reilly’s daughter has made two cards for Albertson. Her mom pulls out one, decorated with a smiley face surrounded by a heart, and reads it aloud:

Dear Mr. Albertson:

Today is the 16th of August and I will be 10 years old on September first. I just want to make sure you know that I forgive you. I do still miss my dad; I think that’s a life-long thing. I hope you’re feeling O.K.

bye bye,

Siobhan

Albertson blows out a heavy sigh, and silence again overtakes the room. Finally, Edwards speaks, asking the convict how the card makes him feel. His reply seeps out slowly, barely rising above a whisper:

“It almost feels fragile, you know? The resiliency of a child is incredible. The willingness to forgive is incredible.”

O’Reilly nods, and then describes for Albertson the chain of events he triggered.

She talks of her initial hatred toward him, of her belief early on that he should rot forever behind bars. In a low voice that breaks with sobs but never swells with anger, she describes the reminders that punctuate her days — the special songs on the radio, the sight of a bicyclist on the road, the graduations, first communions and other occasions now shared by three instead of four.

Recalling the day her husband was killed, she relates in painstaking detail their last exchange of words, the fear that descended when he didn’t come home, the horror when a sheriff’s deputy arrived at the house, her daughters’ expressions as she gave them the news.

Albertson sits frozen, his face contorted.

“Forgive me,” he says when O’Reilly finishes, his voice cracking. “I know the tragedy I’ve caused. I can see it. I don’t know how to fix it — I’m left with no way to fix it. I just have to feel it.”

O’Reilly keeps her moist eyes trained on his face. “Some days all I can do is feel the pain too,” she says. “There is no fixing.”

Two hours have passed in the windowless room.

IN the months before his encounter with O’Reilly, Albertson made a shocking confession to Edwards: I may have hit him on purpose.

For some, this information — that the death on that Sonoma County road may not have been accidental — would have changed everything. O’Reilly took a few days with the news, and came to a different conclusion.

“The thought of turning back and becoming angry and spiteful just seemed so draining,” she recalled. “I didn’t have that kind of energy in my life. I decided it was better to stay on this path.”

At their meeting, this difficult topic comes up. O’Reilly tells Albertson that she believes it took courage for him to make that admission, and that “of the two of us, in my opinion, you’ve got the tougher row to hoe.”

“We both wake up and Danny’s not there,” she continues, “but I don’t have to live with knowing I took his life . You’ve taken full responsibility. Maybe this is a chance to redeem yourself.”

Albertson looks down, his shoulders slumped. Then, haltingly, he shares his story — what happened on the road that day, and what came before.

He talks of five years of sexual abuse at the hands of his father, of buried memories and stifled rage, of drug addiction, 14 years of sobriety, a broken back, a fateful relapse. The night of the accident, he was out of medication and desperate for relief from pain. No one, he says, would help, so he sat in his truck and drank.

Intoxicated, he called his girlfriend for a ride, but she was disgusted and told him a DUI arrest would serve him right. Angry, he took to the highway, to check himself in to a hospital in St. Helena. Along the way, on curving Mark West Springs Road, he saw a bicyclist.

“Everything was jumbled,” he says, as O’Reilly sits riveted by his words. “There is a part of me that remembers swerving toward Danny . There’s a part of me that remembers hitting the guardrail. I sat in the truck, I was bleeding. The CHP came and I faked like I had a gun . I wanted to get shot.”

After a hushed moment, Albertson continues. The stranger on the bike, he concludes, paid a price for a lifetime of rage against a father who raped him and a mother who didn’t stop it.

“Does this give me an excuse to do what I did?” he asks. “No.”

NEARLY four hours have gone by, and it is time for this unlikely duo to reach an agreement. O’Reilly asks Albertson to remain active in Alcoholics Anonymous, to continue therapy and to share his story so it may dissuade others inclined to drink and drive. He says he will.

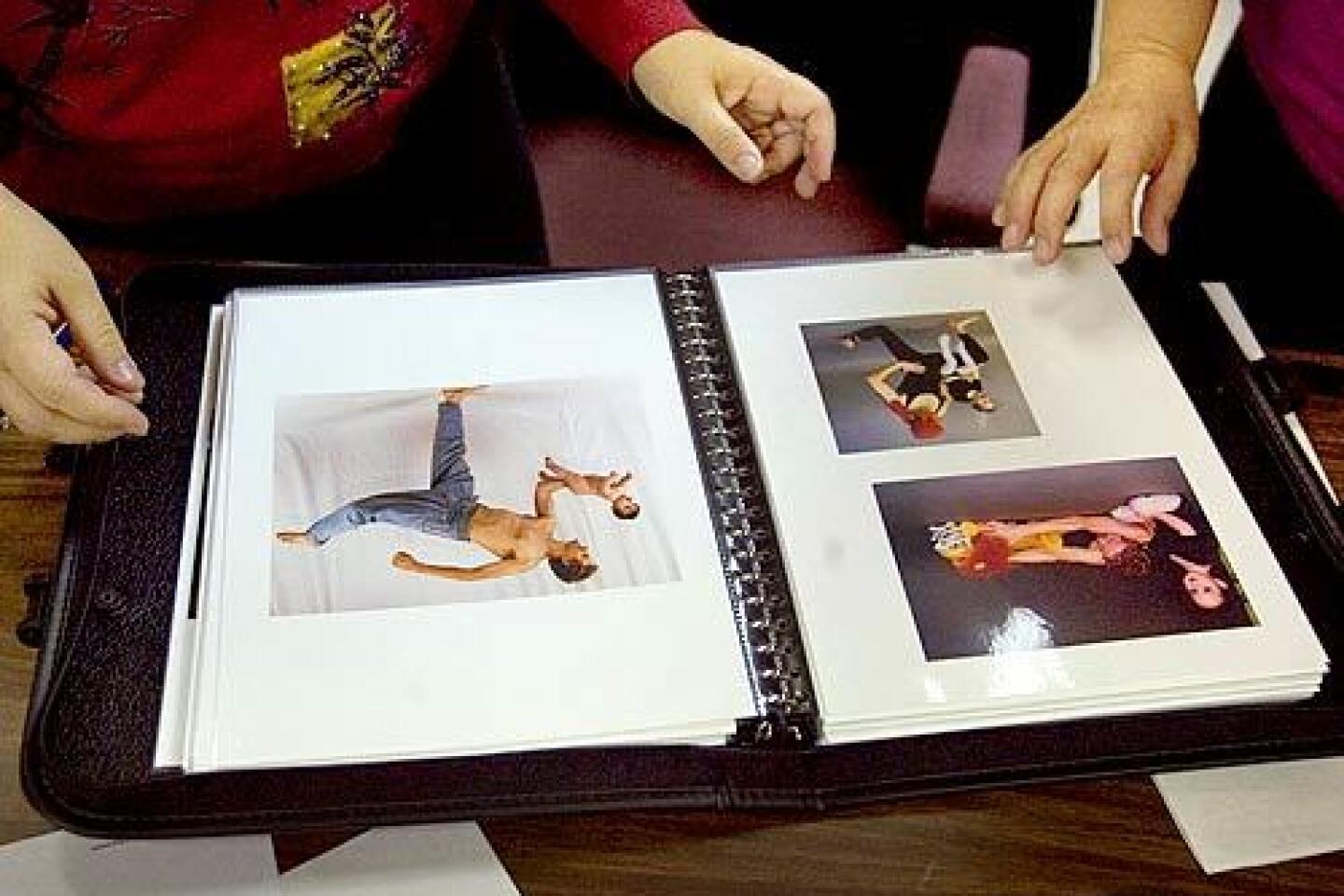

O’Reilly then opens a photo album, showing Albertson shots of her husband’s headstone, followed by a parade of pictures depicting his rich, happy life. The convict thumbs through them slowly, carefully, for a long time.

How do you feel? Edwards asks.

“Looking at those pictures,” he replies, “it was such a wonderful life. And what happened is so tragic. It’s my responsibility.”

“Don’t feel sorry for yourself and go backward,” O’Reilly cautions, her voice turning stern.

“No,” he says, “I’ve got that real clear.”

The two exchange rosaries, and O’Reilly gives the convict a bracelet from her younger daughter. He fingers it gingerly, appearing locked in a trance.

Edwards, attempting to sum up the day’s journey, offers a bit of wisdom. The goal, she says, is to make some meaning out of the catastrophe that united these lives — “not sense, but meaning.”

They part. As she passes back through the cyclone fence topped with coiled razor wire, O’Reilly recalls the words of a Catholic nun who ministers to prisoners in Mexico:

Forgiving is hard, but not forgiving is harder.

A week passes. O’Reilly says she feels lighter, unburdened. The encounter has also left her feeling empowered, which she did not expect.

What happened in that room, she says, was true justice, “participatory justice.” It may sound petty, she adds, but she drew strength from watching her husband’s killer sit at that table and witness the devastation he caused.

“If I have to feel this horrible and struggle to find meaning in this loss, I want to make sure he is struggling — and working on problems he used to deny,” she says.

Albertson’s feelings in the aftermath, he confides, are “up and down and sideways.” He is emotionally drained, frequently depressed. But he feels uplifted by O’Reilly’s willingness to meet him, and calls her forgiveness “an incredible, humbling gift.”

The convict is wearing the bracelet made by the little girl in Sonoma. Those cards she sent are on display right beside his bed.

jenifer warren@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.