Keeping it real, kind of

Paul found God on the road to Damascus. Columbus discovered America on his 32nd day at sea. Now, after decades in public life, Hillary Clinton has gone and found herself among the voters of New Hampshire.

It was a genuine Sally Fields moment -- of the star connecting to her fans. “I listened to you,” Clinton said in her victory speech, “and I found my own voice.”

Desperate to find transcendent meaning in the momentary political preference of a couple of hundred thousand New Hampsherites, pundits almost unanimously embraced the conclusion that what Americans wanted in their commander in chief was a human, preferably one who acted genuinely, authentically human.

It didn’t take much really -- misty eyes and an expression of frustration. But that was enough, apparently, to prove to a sufficient number of voters that Clinton was indeed not just a real human but a real female human.

“This is her essential self,” crowed one of her biographers, Carl Bernstein, on CNN, as if the candidate had finally dug deep enough to strike something real. “Hillary is being more like Hillary,” said NBC’s David Gregory. And they all agreed that being herself made her seem more “human.” What a brilliant campaign strategy!

But not everyone would have predicted that Clinton’s emotional moment would play so well. On the very day Clinton allowed her feelings to seep through her famously controlled exterior, iconic feminist Gloria Steinem argued in a New York Times Op-Ed article that Clinton could never employ Barack Obama’s moving public style “without being considered too emotional.” Leave it to Clinton to prove her wrong.

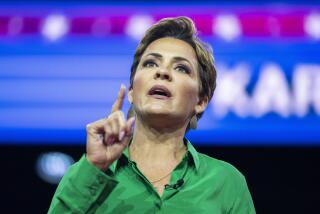

The “politics of authenticity” mean different things at different times. In the late 1960s and 1970s, for white men, it meant being earthy and organic in a phony, establishmentarian world. For minorities and women, it meant having to fit into a narrowly drawn political definition of group membership. Traces of that thinking still linger. You’ll still hear murmurs about whether this or that candidate is black or Latino enough. And don’t forget that time Steinem called Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison a “female impersonator” because the Texas lawmaker wasn’t a strong supporter of abortion rights.

For years, some feminists held that politics defined the boundaries of authentic womanhood, and women in general have been convinced that to wield corporate power, they have to obscure most attributes we commonly associate with femininity.

Unlike other qualities, such as honesty or kindness, it’s hard to isolate objective behaviors that we can automatically associate with being authentic. We call someone honest who consistently utters the truth and doesn’t steal. We characterize someone as kind if they perform acts of kindness. Authenticity, on the other hand, is generally best discerned in its absence. We like to think we know a phony when we see one (Mitt Romney perhaps?). But without any hard and fast rules about what constitutes the authentic, we generally consider it to be that which we most recognize in our own lives as being “real.” We think authentic people are the ones who seem to be like us.

At the same time, however, you don’t actually have to be real to be real. As the late American philosopher Robert Nozick noted, some literary characters -- Raskolnikov, Hamlet, Sherlock Holmes to name a few -- are “more real than life” because of the vividness, sharpness of detail and “integrated way in which they function toward or are tortured over a goal.” It’s these characters’ “concentrated centers of psychological organization” that make them appear so authentic. For all their uniqueness, we recognize them as paradigms, models and epitomes. Novelists who can create hyper-realistic facsimiles of reality are called geniuses. So are campaign strategists.

It’s not as if American voters aren’t aware that campaigns constantly mold and position their candidates to fit the presumed desires of target audiences. An October study by the Project for Excellence in Journalism found that early in the primary contest, 63% of election stories focused on political and tactical aspects of the campaign itself, compared to 17% on the candidates’ personal backgrounds, 15% on their policy proposals and 1% on their past public performance. In other words, we probably know more about the machinations and posturing of campaigners than we know about their platforms. As with reality TV, we’re aware that there’s little in the political theater of a presidential campaign that isn’t scripted. But that doesn’t seem to prevent us from believing we know these people. Manufactured authenticity is better than none at all. Remember what that female anti-hero in “Big Brother U.K.” tried to warn us about a few years back? “We were manipulated into stereotypes,” she said after watching the final edit of the show. “That wasn’t me, it was a caricature of me. ... The power of the production is incredible. It’s not real. Don’t be fooled!”

But would she have said that had she won? In the meantime, no one else is complaining.

grodriguez@latimescolumnists.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.