The Munitz collection

The world’s richest art organization was facing hard times in spring 2003.

On a Wednesday in late March, seven security managers were called into a conference room at the J. Paul Getty Trust’s hilltop campus in Brentwood and told that their positions had been eliminated.

It was the first in a series of layoffs and cutbacks that year at the Getty. The trust’s endowment had lost more than $1 billion in two years, mostly because of declining stock markets. Despite its reputation for bottomless wealth, the Getty was pinching pennies.

But the cuts didn’t apply to everyone.

Days after the security layoffs, trust Chief Executive Barry Munitz drove up the Getty Center’s winding driveway in a new Porsche Cayenne.

The Getty paid $72,000 for the SUV. When ordering it, Munitz told an aide it should include the “best possible sound system,” “biggest possible sunroof” and “power everything....”

Munitz is a man of grand appetites, a player among Los Angeles’ elite whose effusive personality and risk-taking management style have won praise even as they have alienated some of the trust’s most respected staff members.

During his seven-year stewardship, Munitz has led the Getty through a trying period of change. But he has also pushed the limits on how nonprofit organizations use their resources.

Documents show that Munitz has spent lavishly, traveling the world first class at Getty expense, often with his wife, staying at luxury hotels and mixing business with pleasure.

Munitz’s total compensation topped $1 million in 2003, placing him among the highest-paid foundation chiefs, museum directors and university presidents in the nation, according to published salary surveys and a Times review. That same year, as the Getty eliminated raises for other employees, Munitz asked for an increase that brought his 2004 pay package to more than $1.2 million.

Getty officials justified his compensation by saying the trust is a uniquely complex institution that places extraordinary demands on its leader. Yet, while running the Getty, Munitz has also had time to serve on more than a dozen corporate and nonprofit boards, work that earned him at least an additional $180,000 in cash or stock options in 2004.

In balancing outside pursuits and in managing the Getty, employees and critics say, Munitz has blurred the line between his own interests and those of the organization he leads.

Records show that he has employed the Getty’s money and reputation to do favors for friends, once using trust letterhead to petition a state agency on behalf of a securities trader — related to his wife by marriage — convicted of fraud in the 1980s.

He has dispatched his office’s driver to pick up videotapes of recent episodes of “Law & Order” and “The West Wing,” instructed his assistants to express mail him umbrellas when he travels, and asked them to track down items for his wife, Anne T. Munitz.

“ATM saw in Europe but can’t find her Tropicana blood orange juice, no pulp, not from concentrate,” Munitz said in one dictation. “Can you look on the website and find out where we can get this on a regular basis locally?”

Under the tax code, nonprofits must use their resources for the public good. The Internal Revenue Service considers excessive pay, travel and perks to be “self-dealing”: the illegal use of tax-exempt resources for private benefit.

Last year, the IRS launched an initiative to review executive compensation at nonprofits after a series of abuses were discovered elsewhere in the country. Congress is also considering the first major overhaul of laws governing nonprofit organizations in 30 years, spurred by reports that some of them have misused tax-exempt money.

In written responses to Times questions, Getty officials said the board explicitly authorized Munitz’s pay, travel and participation in outside activities.

A recently completed IRS audit of the Getty’s 2001, 2002 and 2003 fiscal years found nothing wrong with Munitz’s pay, perks or financial practices, they said. They said the trust adhered to tax regulations. Getty officials conceded that two grants questioned by The Times had been made in violation of the tax code, but said the deficiencies were later addressed.

No matter how regulators view Munitz’s actions, the deeper wounds may be internal. His critics say he has filled the Getty’s top ranks with loyalists, transforming the trust into a bitter, divided place that has hemorrhaged talent.

“Barry and his key staff members not only lack the expertise, but have little regard — and actually seem to have contempt — for those who do have it,” said Barbara Whitney, who resigned in 2004 as the museum’s associate director for administration and public affairs.

“The people who dreamed the Getty Center, designed it, worked together, built it, and then opened it to the public with such acclaim and success — within a few years of the opening, those same people were being treated like idiots by a handful of bureaucrats that Munitz brought in,” she said.

Internal tensions boiled to the surface in October, when Getty Museum Director Deborah Gribbon abruptly resigned, citing critical differences with Munitz. In April, William Griswold, Gribbon’s deputy and interim replacement, told Munitz that he was not interested in her job.

John H. Biggs, chairman of the Getty board, offered unqualified support for Munitz in a letter to Times editors.

“The board believes Dr. Munitz has done a remarkable job leading the Getty,” wrote Biggs, former chief executive of TIAA-CREF, the investment fund for education professionals. “He has assembled an outstanding management team. He has instigated necessary and important change at a complex organization and positioned the Getty to accomplish extraordinary public service.”

In an interview in November, Munitz defended his practices and said the animus directed at him was a byproduct of the changes he was hired to make:

“This is an institution that takes risks. That’s what we’re in business for. The board says often: If we’re blessed with these resources, we should be nimble and we should be opportunistic. If I was sitting with you here in seven years, and you’d say, ‘What do you regret, what do you think went wrong, what surprised you?’ — if there was nothing on that list, I would tell you I had failed.”

At the helm

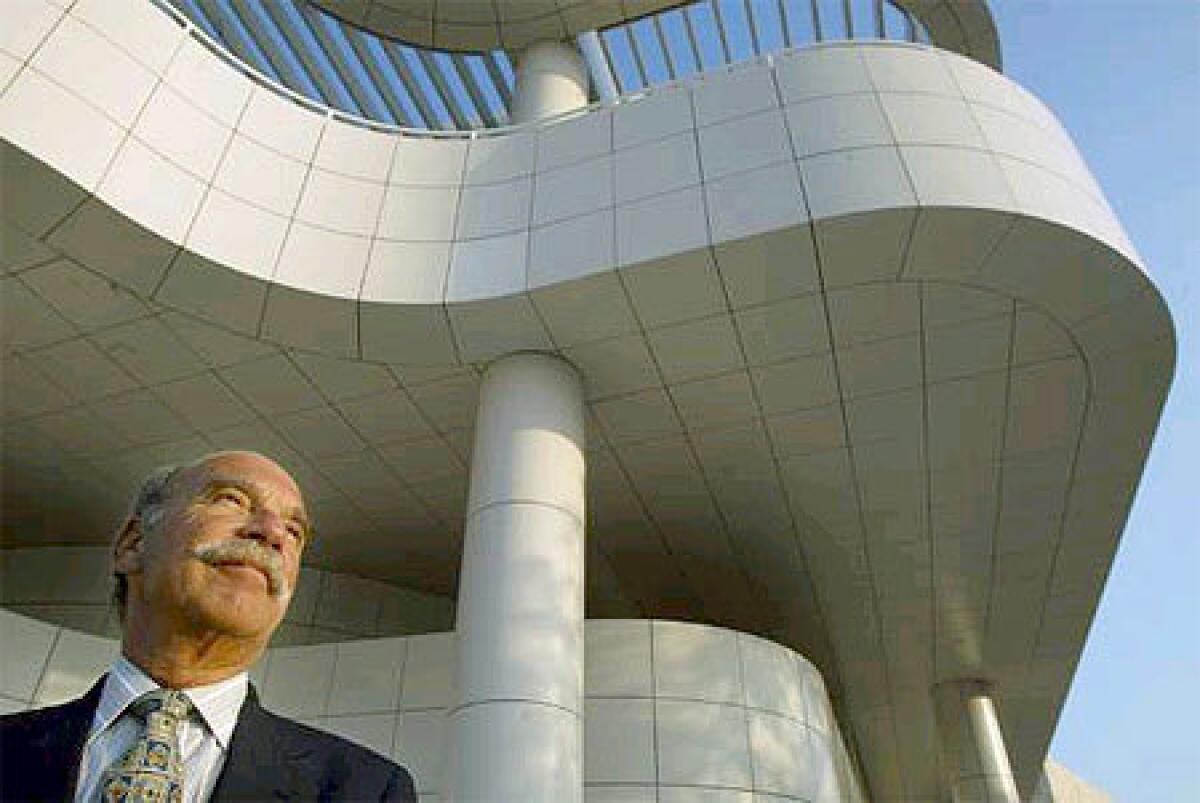

Presiding over a large blond wood conference table at the Getty Center last fall, Munitz, 63, exuded the garrulous charm that helped propel him from tough origins in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood to a perch in the Brentwood hills.Deeply tanned and dressed with customary brio in a purple shirt, tie and matching sweater, he talked about the challenges he faced at the trust early on, and the firestorm that followed Gribbon’s departure.

Supporters describe Munitz as shrewd and analytical, a tireless networker.

He counts billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad and former Paramount Pictures head Sherry Lansing among his closest friends. Leon Panetta, White House chief of staff under President Clinton, met Munitz when Munitz was chancellor of the California State University system. Panetta called him the savviest politician he had ever encountered in academia.

Munitz arrived at the Getty in January 1998, replacing Harold Williams weeks after the opening of the trust’s Brentwood campus.

When J. Paul Getty died in 1976, he left his museum with $700 million in Getty Oil stock and a broad directive to promote the arts and humanities. The trust evolved into seven discrete programs with, at times, divergent agendas. In the decade preceding Munitz’s arrival, the organization had spent more than $2 billion to build the Getty Center and expand its collections.

“Part of my task seven years ago was to instill some sense of economic reality to the institution,” Munitz said.

It was a position he was accustomed to. He came to the Getty with no art pedigree but a long resume in education and a bottom-line mentality developed working at Maxxam Inc., the Houston-based conglomerate controlled by takeover tycoon Charles Hurwitz.

Munitz was no stranger to controversy or tough choices.

He had been chief executive of a Hurwitz-controlled savings and loan when it failed in 1988, costing taxpayers $1.6 billion. Munitz and others were sued by regulators, who alleged, among other things, that company executives had paid themselves large bonuses and arranged golden parachutes as the thrift went under. Munitz settled the case in 1999 without admitting or denying the allegations.

Maxxam assumed responsibility for his portion of a $1-million fine, and he agreed to a temporary prohibition against holding positions with certain fiduciary responsibilities.

Munitz left Maxxam in 1991, then spent six years at CSU, which he led through the state’s early 1990s budget crisis, partly by raising tuition and instituting a corporate-style merit pay plan for the faculty. He was credited with raising the institution’s profile and pushing for a new campus serving Ventura County.

In his first year at the Getty, Munitz eliminated two of the trust’s seven programs and folded a third into the museum.

The restructuring left a trail of bitter former employees, but many observers agreed it focused the Getty on its strengths: the Getty Museum, with its collection of pre-modern art and antiquities; the Conservation Institute, which restores and protects art worldwide; the Research Institute, with its 800,000-volume library centered on the visual arts; and the Getty grant program, now called the Getty Foundation.

Munitz labored to make the Getty — long perceived as aloof from the community around it — more inclusive. On his watch, the trust directed millions of dollars to local artists, added bilingual programming and subsidized busing to the Getty Center for schools. The hillside complex became Southern California’s biggest art draw, welcoming more than 1 million visitors a year.

He took a chance by borrowing $525 million between 2002 and 2004, betting that growth in the trust’s investments would outpace payments on the debt, a gamble that has paid off so far.

“I don’t think anybody thought there would be tight times at the Getty. There have been,” said former Los Angeles schools interim Supt. Ramon Cortines, the only member of the 12-member Getty board who agreed to an interview. “He did a damn good job in a tough situation.”

However, Munitz’s strategies for building the museum’s collection were controversial. When he engineered a deal to award $12.5 million to London’s Courtauld Institute of Art, from which the Getty was later allowed to borrow artwork, one prominent British art historian castigated the arrangement as “cash for paintings.” American critics wondered whether the trust was foolish to pay so much for pieces it could not keep.

Also controversial was Munitz’s delegation of authority to Jill Murphy, his 33-year-old chief of staff, whom he had brought with him from CSU. He had fostered her career since meeting her at the Jammin’ Salmon restaurant, where she worked while attending Cal State Sacramento.

Munitz gave her broad administrative responsibility and, though she had no background in art, trusted her to help plan the schedule for Getty shows and weigh in on acquisitions, staff said.

“Murphy was recognized ... as someone who wielded extraordinary power, not always politely, and with whom disagreement was not an option,” said Burton Fredericksen, who directed a program at the Getty Research Institute till 2001.

Murphy declined to comment. Munitz defended her as a brilliant talent, even as he acknowledged that she had “sharp elbows.”

According to Whitney, the ascendance of Murphy and other newcomers, combined with the departures of more than a dozen high-profile members of the Getty’s old guard, created a culture of favoritism and anxiety.

“To be fair, I think Barry made a good start reorganizing the Getty Trust,” said John Walsh, the Getty’s former museum director.

“But for a couple of years there have been signs of big trouble. Getty people in the other programs as well as the museum have been volunteering nothing but unhappy stories about how the trust is run.”

When he left CSU for the Getty, Munitz went from begging for money to sitting atop the Getty’s billions. Unlike most museums, the trust funds its operation from its $4.9 billion endowment, rather than donors or memberships.

The Getty’s mission is so broad and its pockets so deep — even in tough times — that Munitz has spread wealth in a fashion few other nonprofit leaders could.

When he was a Princeton University trustee, he hired the university president’s daughter straight out of college. A chess enthusiast, he briefly established a Getty Chess Project Office, flying a chess-playing trust security guard to Israel to observe the Kasparov Chess Academy.

After Munitz met with a Clinton administration aide, the Getty paid $500,000 to a public relations firm promoting a White House education effort about the future of Mars.

His office spent more than $20,000 — including $1,000 for custom-made gift-wrap — on artwork for departing trustees, even though the trust’s attorney warned that such gifts could violate both the tax code and the terms of J. Paul Getty’s will.

Generous personality

To some, such decisions simply reflected Munitz’s generous, all-embracing personality. He is known for showering friends with notes and mementos, as well as newspaper clippings, magazine articles and books he has devoured. He has been known to sign official correspondence with “very warm hugs.”But many staffers saw Munitz squandering the trust’s resources on what Margaret MacLean, an anthropologist who used to work for the Getty Conservation Institute, called “shallow vanities.”

In 2003, when other Getty departments were urged to cut back, Munitz’s Office of Senior Advisors, a group of specialists who report directly to him, had a budget of more than $1 million. Among the advisors was a former intern whom the Getty paid while she worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Jack Miles, a former Los Angeles Times book editor and editorial board member, earned more than $100,000 as an advisor in 2003. “My job is loosely enough defined,” Miles, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of books and essays on religion and foreign affairs, said recently. “I’m not routinely involved in any component parts of the Getty.”

Former literary agent Norman Kurland lives in London and was paid $50,000 in 2003. He was the Getty’s liaison to the Courtauld, but also performed other tasks, records show.

Munitz once told an aide to write to Kurland: “Happily for me but unfortunately for you since you are in London, there will from [time] to time be semi-professional related activities that I hope you will be able to help me with. One is coming up on Thursday ... a Bloomsbury book auction focusing on chess volumes.... Would you find it possible to wander by ... and have a look at several items for me?”

Munitz’s office has its own grant budget, from which it has awarded more than $2 million. Getty officials said Munitz does not personally award grants.

The office also controls the President’s Opportunity Fund, a $10-million contingency account from which two grants worth more than $1.5 million total have been awarded.

It is a measure of his autonomy that in October 1999, records show, two grant payments totaling more than $90,000 were rushed out at Munitz’s direction without a review or signed agreements in place. Getty officials said the lapses were “discovered quickly and resolved” by executing grant agreements. Documents show the trust began the review process months after checks were issued.

In 2003, Munitz awarded an $18,000 grant to the Music Center shortly after it hired Stephen Rountree, a longtime Getty executive as its president. Munitz said in a letter that the money should be used, in part, for “equipping and furnishing” Rountree’s new office.

Before Rountree left the Getty, his department made a grant of $10,000 in trust funds to sponsor the Southern California Leadership Network’s Leader of the Year Luncheon, records show.

The group’s Founder’s Award honoree: Barry Munitz.

Ambassador at large

In May 2000, Munitz and his wife traveled to Tuscany for a stay at the Villa Ortaglia, a 15th century farmhouse built by the Medici family and surrounded by vineyards.Over the next eight days, they toured museums and churches whose artworks were restored with Getty funds, and twice were hosts of dinner parties put on at trust expense.

All told, records show that their trip cost the Getty $35,107, including more than $13,000 for first-class airfare, half of the villa’s $21,000 rental fee, $466 for “wine supply for all meals” and a $35 customs charge for “Getty umbrellas shipped to villa for use during visit.”

In his role as the Getty’s ambassador, Munitz has traveled broadly, visiting museums and trust-funded restoration projects across the globe.

From 1999 to 2002, he flew first class on at least 30 trips, to destinations as far away as Salzburg, Austria, and as near as San Francisco. He flew coach three times. He stayed at the Four Seasons in Philadelphia and Chicago, and at the Palace in New York, at rates of up to $505 a night.

In the last half of 2002 alone, the Getty reimbursed Munitz for all or part of 13 trips. He traveled abroad five times, including another trip to Tuscany, this one costing $24,000. One trip alone, to Australia with his wife, cost the Getty more than $29,000.

Getty officials were aware that travel expenses could expose the trust to criticism.

“Travel is a highly scrutinized area,” noted a version of the Getty’s trustee travel policy, dated February 2000. “For an organization such as the trust — one that has been granted tax-exempt status through its commitment to charitable causes in the visual arts and humanities — it is perhaps even more important that it avoid criticism that might be directed at apparent misuse of the trust’s endowment funds in the area of travel expenditures.”

The policy said board members could fly business class on long flights, with first class allowable only under special approval. It added that the use of “resort-type, luxury and deluxe hotels by trustees is discouraged.” Cortines said he had never flown first class at Getty expense in nine years on the board, even when trustees met overseas.

“I don’t approve of first class,” he said.

Those policies didn’t apply to Munitz. When a staffer questioned one of his earliest first-class flights, the response in a handwritten note read, “Barry is not applicable to any restriction here.”

Staff also debated how to treat expenses incurred by his wife. From mid-1998 to 2002, records show, the trust paid more than $60,000 on airfare for Anne Munitz, most of it first class.

Biggs said the board decided Munitz should travel “in a manner appropriate to his position” and that his contract explicitly allowed his wife to travel with him for business at trust expense.

“When we hired Dr. Munitz, this is something the board told him they felt was important and specifically encouraged him to consider it part of his responsibilities,” Biggs, the trust’s board chairman, said in a letter to The Times.

When the Munitzes took a six-day trip to Hawaii in July 2001, for example, the trust covered half their hotel bills, $1,002 a night at the Hyatt Regency Kauai and $986 ar night at the Ritz Carlton Kapalua, as well as all of their first-class airfare and car rental.

“Anne Munitz accompanied Dr. Munitz on this trip to participate in activities by which protocol, tradition or necessity require a spouse’s attendance,” Munitz’s expense report said, listing tours of the National Tropical Botanical Gardens and the Gorilla Foundation’s research facility, and a meeting with school officials as the trip’s business purposes.

Among two dozen large nonprofits consulted by The Times, only one other foundation president regularly flies first class — Patty Stonesifer of the $26-billion Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, who does not accept a salary.

At the $4.1-billion Pew Charitable Trusts, “we have a very strict policy that everybody flies coach,” general counsel Jamie Horwitz said.

No other U.S. private foundation ranked among the top 10 in assets reimburses spousal travel as the Getty does. Neither do most major arts institutions.

Philippe de Montebello, director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, pays his wife’s expenses and flies first class only if he pays for it himself, a museum spokesman said.

Harvey Dale, university professor of philanthropy and law at New York University and a “friend and admirer” of Munitz, said spousal travel is avoided at most nonprofits.

“My personal preference is that it not be paid for by the foundation,” he said. “I think, in general, most people who serve on foundation boards and who get compensation can use that compensation to pay for spouses’ expenses.”

In a letter sent to Times editors after the November interview, Munitz said, “We have never denied that my travel and expense responsibilities would be relatively high.... If further reviews of the details, particularly related to spousal travel as overseen by the board, require changes in how we account and reimburse for these expenses, we will implement those improvements immediately — it is that clear and simple.”

Three months after they rented the Italian villa, the Munitzes sailed along Croatia’s Dalmatian coast on a 165-foot yacht chartered by Eli Broad. Also aboard were former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, supermarket magnate Ron Burkle, AIG SunAmerica Chief Executive Jay Wintrob and their wives.

Munitz’s expense report said the trip’s business purpose was assessing the security of areas where the Getty had sponsored study and restoration work on ancient palaces. The Getty reimbursed Munitz more than $7,000 for his expenses and $226 for picture frames he subsequently sent the Broads, Wintrobs, Riordans and Burkles. Burkle and Wintrob later joined the Getty board.

Riordan said he remembered that cruise — and the group’s other annual trips — as vacations.

“They were all pleasure. I can’t think of any business as such,” he said. Told that Munitz had expensed part of the trips, Riordan said: “Anytime there was a ruin or anything, he would spend hours looking at it from every angle.”

Munitz also accompanied the group on two trips to Greece; the Getty reimbursed him for more than $8,000 he paid Broad, a noted art collector, for yacht rental fees and expenses.

In February 2003, Munitz and his wife joined Broad, Riordan, their wives and others for a trip to Cuba. It included a guided tour of old Havana, a dinner concert with members of the Buena Vista Social Club and a short hop across the island on Broad’s private jet. The Getty paid almost $7,000 to cover Munitz’s expenses.

Munitz had hoped to arrange a chess match between Riordan and Fidel Castro, documents show, but it never panned out.

“Fidel chickened out,” Riordan said.

A raise in pay

In early 2003, after absorbing heavy investment losses, the Getty made layoffs, replaced annual raises with one-time bonuses and cut such perks as holiday parties, staff softball games and free coffee and tea, staff said.But as everyone around him tightened their belts, Munitz was lobbying for a raise, records show. He was already among the highest paid nonprofit chief executives in the nation, with total compensation of a little more than $1 million.

In dictations that he directed an aide to send to the trust’s general counsel, he argued that he deserved more.

In a January 2003 dictation labeled “draft,” Munitz described having told Lewis Bernard, then chairman of the Getty board’s compensation committee, that “in tougher times the job was more demanding and had to be rewarded similarly.” Munitz said he told Bernard he “was not concerned that being paid adequately for performance would send the ‘wrong signal’ to colleagues inside the institution or to public audiences.”

Asked about the dictation, the Getty said it “does not accurately reflect the events described or Dr. Munitz’s thoughts or observations.”

In a dictation dated June 2003, Munitz said that, unlike the Getty, other nonprofits paid for chief executives’ housing and helped them get seats on corporate boards. At the time, Munitz sat on three corporate boards for which he was paid at least $180,000 a year in fees or stock options.

Munitz also said the board had not given him retirement benefits on par with his predecessor, Williams. He asked for enhanced benefits, an office for life at the Getty Villa in Malibu, and a bonus when the Villa reopened.

The Getty’s board approved a new contract for Munitz in January 2004. Internal documents show that his total compensation rose to more than $1.2 million, a 16% increase over the previous year.

Biggs said Munitz’s compensation was publicly disclosed in tax filings and well deserved. Salary comparisons conducted by outside experts showed that Munitz’s pay — excluding benefits — was lower than those of many counterparts in the field, he said.

“I have been personally involved with the compensation-setting process in six or seven major nonprofit institutions,” Biggs wrote in a letter to the Times. “The Getty process is as good as or better than any I have known.”

The Getty is hard to compare with any other single nonprofit. Trust officials said they used universities, museums and private foundations as a yardstick.

Still, Munitz’s total compensation — which includes perks, expenses and benefits, all of which the IRS considers — was among the highest of chief executives in those categories in 2003.

The nation’s best-paid university president — William R. Brody of Johns Hopkins — made $897,786 in total pay that year. He oversaw six campuses in the U.S. and three abroad, with a budget of more than $4 billion. The Getty’s operating budget was less than one-tenth of that.

“This kind of comp may be acceptable in the corporate context, but it is just not acceptable in the nonprofit,” said James Fishman, a professor of nonprofit law at Pace Law School. “The Getty is not paying taxes. Every taxpayer is really subsidizing the Getty. It’s a stream of money flowing away from the U.S. Treasury.”

Undaunted

Until 2004, the internal friction that bedeviled the trust under Munitz had remained largely within the Getty’s walls. Then, in October, it spilled into public view when Gribbon walked out unexpectedly as director of the museum. As she left, Getty staff lined up on both sides of a museum corridor, giving her a standing ovation.Finding her replacement at a time when five other major arts organizations in the country — including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art — are also looking for directors, is just one of several challenges the trust faces.

In May, Italian authorities announced plans to try Marion True, who works for Munitz as director of the newly renovated Getty Villa — scheduled to reopen later this year — for allegedly dealing in looted antiquities.

Both True and the Getty deny any wrongdoing. Her trial will start this summer, months before the planned reopening.

Consistent with his character, Munitz is undaunted.

In March, he floated the idea of opening satellite Getty Museums around the country or perhaps beyond.

“I have no personal agenda to advance; I took this job because I wanted to make a difference,” Munitz said in his letter to The Times. “There are thousands of transactions at an institution like the Getty, so undoubtedly when you look carefully there will be mistakes.... The issue is what we do about them. In the Getty’s case, we make the necessary changes to move forward in the most responsible manner.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.