California Legislature’s new era may mean more productive Capitol

SACRAMENTO — It’s the end of an era for California’s much-maligned Legislature, thankfully, and the beginning of a more promising future.

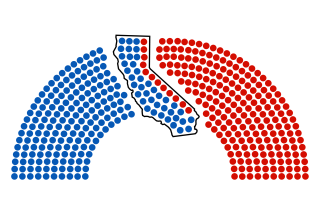

The lawmakers’ core problems — polarization, paralysis — have had less to do with the politicians themselves than the system in which they’ve been elected and been operating.

That system effectively ceased Friday night when the gavel fell on the Legislature’s two-year session.

The new system — the product of voter-approved reforms — hopefully will produce more pragmatic, less ideological legislators committed to negotiating long-term fixes to California’s problems.

“I think there’s going to be a fairly significant change, although you may not see it for a couple of years,” says veteran Republican consultant Marty Wilson, who’s working with the California Chamber of Commerce to elect more business-friendly legislators.

“Many new folks coming up, I just think they’re a better quality legislator — both Republicans and Democrats. They’re not the same old partisan hacks. There are plenty of partisan hacks, but there’s a better quality coming to Sacramento this November.”

This is what’s happening:

•Under the new “top two” open primary system, many runoff candidates in November are being forced to compete for votes among a wider spectrum of the electorate. No longer can they depend on just the party core. They must appeal to independents and members of the other party. This is especially true in the 20 legislative contests in which two members of the same party are running against each other.

“We should get a sizable group of moderate Democrats; maybe some moderate Republicans, too,” says Allan Hoffenblum, publisher of the California Target Book, which handicaps legislative and congressional races.

•The districts no longer are gerrymandered to ensure victory for one party, usually Democratic. They were drawn honestly by an independent citizens’ commission, creating more competition.

“There are more competitive races than we’ve seen in a couple of decades,” Hoffenblum says.

•Newly elected legislators will be entitled to more flexible term limits. They will be limited to a total of 12 years but can serve them all in one house. The current limits are six years in the Assembly and eight in the Senate.

Because many will be around the Capitol longer to witness the consequences of their policy decisions — and be held accountable — legislators will have more incentive to tackle long-term problems, such as an outdated tax structure, burdensome business regulation and inadequate education.

House leaders and committee chairmen will be able to acquire the expertise, self-confidence and power to stand up to special interests. OK, maybe that’s fantasy, but it’s more likely to become a reality than under the current term limits.

Even more likely: New legislators arriving in Sacramento no longer will feel compelled to immediately begin jockeying for their next office because of tight term limits. They can focus on public policy.

“That’s probably the biggest sea change we’ll see almost immediately,” Wilson says.

Already one reform that took effect during the just-concluded session has led to a dramatic improvement in Capitol behavior. The Legislature twice beat the July 1 fiscal year deadline for budget enactment rather than vacillating far into summer.

That’s because voters in 2010 approved an initiative allowing lawmakers to pass a budget with a majority vote, rather than needing two-thirds.

But the session might have achieved much more if all the reforms had already been in place — if there had been more legislators tuned to the broad electorate and fewer worried about their narrow political bases.

Start with the simple issue of taxes. At least it used to be simple. Past governors could temporarily raise taxes with Republican support when there were fewer conservative ideologues and lawmakers cowering before professional demagogues.

Gov. Jerry Brown didn’t even try, having made an ill-fated campaign pledge to surrender to the voters his and the Legislature’s constitutional power to raise taxes. Then he couldn’t muster a handful of Republican votes to put the issue on the ballot.

“I took them to dinner, I wined and dined them, went to their houses, met their wives, introduced them to my wife,” Brown recalled to reporters last week.

“And people said they had two conclusions: ‘Brown doesn’t know what is happening in Sacramento today because you will never get Republican votes.’ Or that ‘Brown is so arrogant that he thinks he can get Republican votes.’

“Well, we have got to keep trying.”

Brown was forced to trek the signature-gathering route to the ballot with his tax proposal, soliciting financial backing from special interests who, of course, expect the political investment to pay off one way or the other.

The inability — or unwillingness — to enact a budget-balancing tax package was the governor’s and Legislature’s greatest failure in the session.

Another was the failure to pass a comprehensive overhaul of the oft-abused California Environmental Quality Act, the bane of developers and other entrepreneurs. CEQA will be reformed when more business-friendly Democratic moderates are elected to the Legislature.

There were some notable achievements by the Legislature, mostly because of Brown’s pushing.

They included major overhauls of public pensions and workers’ compensation insurance; also abolition of property-tax-wasting redevelopment agencies and the shifting of low-level state prisoners to less expensive local custody (called “realignment” in Capitol-speak).

With reforms en route, the future could be much more productive.

“We may be electing more reasonable types — pro-governance people interested in making government work and not necessarily in the pockets of special interests,” says GOP strategist Rob Stutzman.

“It’s fair to say this is a turning of the page.”

Opening into a hopefully more upbeat chapter.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.