Clinic says it warned L.A. County that boy might be an abuse victim

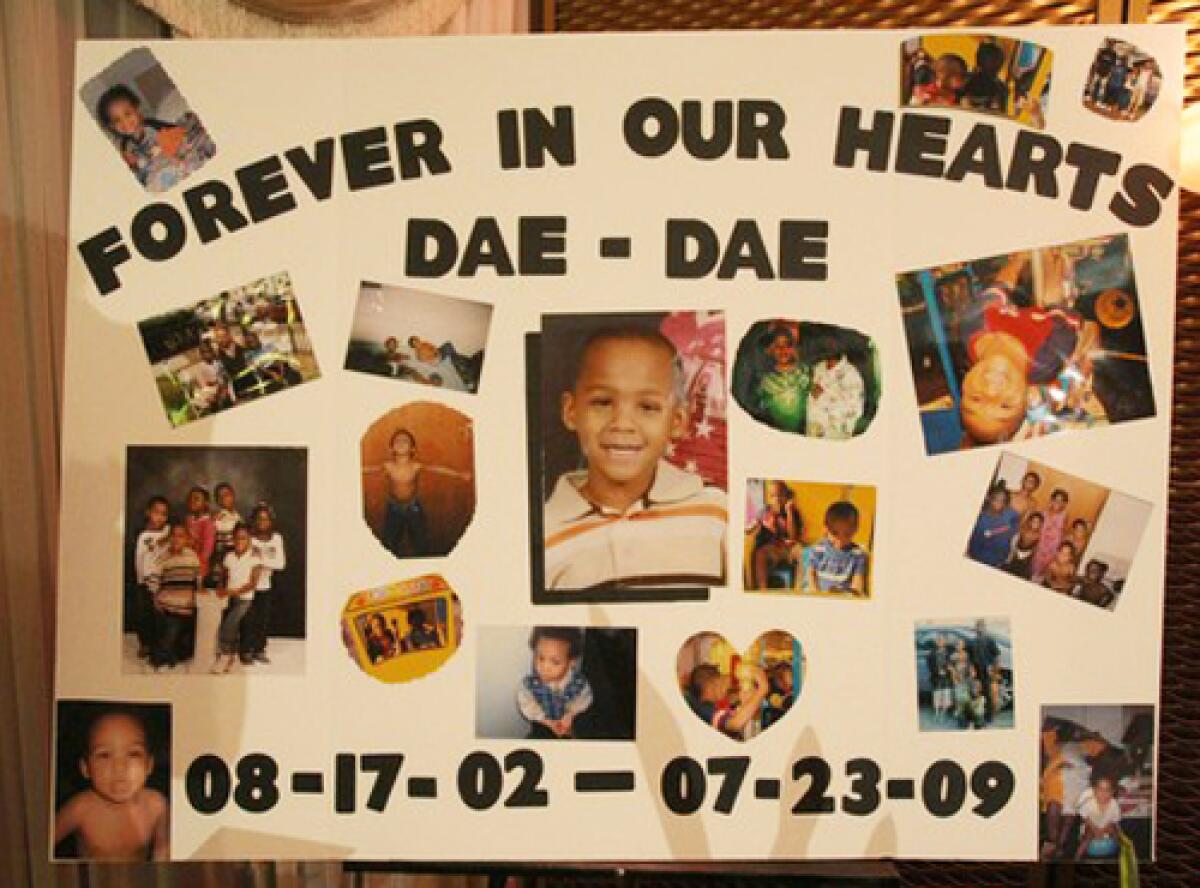

Officials at a clinic that treated Dae’von Bailey six weeks before he was found beaten to death said Friday that their staff had warned social workers he might be an abuse victim, contradicting an account by the Los Angeles County child welfare department about how it dealt with the abuse allegations.

According to the clinic’s chief executive, a pediatric nurse practitioner who examined the boy in June told a county social worker that she thought his mother’s former boyfriend might be abusing him and questioned whether Dae’von should live with the man, Marcas Fisher.

That account differs from a timeline presented by the Department of Children and Family Services to county officials. The department’s report said the medical provider who examined the boy found “there were no signs of physical abuse” and “she had no concerns for Dae’von.” The social worker who looked into the allegations labeled the charge of abuse “unfounded” and closed the case. In both April and June, social workers examined allegations that Fisher had abused Dae’von -- and both times decided to leave the boy with him.

The 6-year-old was found beaten to death last week, and police have issued a murder warrant for Fisher.

The clinic’s role in the case underscores how the system designed to protect children from abuse can fall short. Clinic officials said they expressed their concerns about abuse in phone conversations with the social worker. Experts said they should have put their warning in writing.

Jim Mangia, chief executive of St. John’s Well Child & Family Center, said the nurse practitioner examined the boy at one of the center’s clinics in Compton on June 4 after an adult at the boy’s school reported that Dae’von had said Fisher punched him in the stomach.

The nurse practitioner checked Dae’von’s stomach and found no bruising. But Mangia said blows to the stomach don’t always produce visible injuries. The nurse noticed scratches on the left side of the boy’s face. Alone with her in the exam room, Dae’von said he had been hit by Fisher in the stomach, chest and, before that, the nose, Mangia said.

Dae’von was accompanied to the doctor’s office by a woman who identified herself as his mother. After the private interview, she came into the room. At that point, Dae’von changed his story and denied Fisher beat him, Mangia said.

“The inconsistency is a perfect example of what happens when a child is abused,” Mangia said. “Children change their story when there’s either a threat or they’re in fear of a threat.”

A few weeks earlier, the clinic had treated Dae’von for a bloody nose, Mangia said. At the time, the injury didn’t seem unusual. But after Dae’von said he had been beaten, the nurse practitioner reconsidered the significance of the bloody nose, he added. She called the county’s child abuse hotline to report her concerns, he said.

Later that day, the nurse practitioner called the social worker on Dae’von’s case and said she thought the boy might be the victim of abuse, Mangia said. She also informed the social worker about the bloody nose, he added.

According to Dr. Linda Tigner-Weekes, the clinic’s medical director, the nurse practitioner specifically raised concerns with the social worker about having Dae’von live with Fisher. “She even asked the social worker, ‘Is it safe to send him home?’ The social worker asked, ‘Do you see any signs of bruising?’ -- which is a dumb question to ask because you cannot rely just on bruising.”

County officials have declined to answer specific questions about Dae’von’s death, which has sparked a public outcry and comes as the family services department struggles to address a pattern in which children have been killed after their cases have come to child welfare officials’ attention.

In response to Mangia’s allegations, Trish Ploehn, director of Children and Family Services, told The Times: “I am not in agreement with what St. John’s portrayal of their communication with our department is, and as soon as we can release those records, we will, and they will clearly refute the information that was provided by them.”

Ploehn, who since taking office two years ago has made better accountability for social workers a top priority, launched an investigation after Dae’von was found dead July 23. On Thursday, she announced several new policies, including more administrative oversight of child abuse cases.

Several key questions have been raised about how the county handled Dae’von’s case. According to Los Angeles police detectives, social workers had approved an agreement between Fisher and the boy’s mother that placed Dae’von in the man’s home. Fisher had been convicted of rape as a teenager and had a criminal record as an adult.

Mangia said the nurse practitioner never sent a written document to the family services department warning that Dae’von may have been abused. The social worker told the nurse during the phone call that there was no need for a written report, Mangia said. In retrospect, “we should have filed some formal report,” he added.

But one leading expert in child abuse law said that if Mangia’s account was accurate, there were several breakdowns in the process.

The social worker should have had the boy examined by forensic pediatricians at one of six county-run centers that specialize in detecting child abuse, said Dr. Astrid Heger, executive director of the L.A. County-USC Violence Intervention Program.

And any medical professional who believes a child has been abused is obligated to send a written report to the family services department.

A phone call “is not good enough. The law requires that every medical professional who suspects child abuse call the hotline and file a written report,” Heger said. “You have to file this report in writing so there’s a paper trail to show you made every effort to protect a child from abuse. In the absence of a written report, it’s like it did not happen.”

Whether the woman who accompanied the boy to the clinic in June was actually his mother, Tylette Davis, remains unclear. Davis, 28, said Thursday that she was not aware of any allegations that Dae’von was being abused. She could not be reached for comment Friday. In an earlier interview, she said the boy and her 5-year-old daughter were living with Fisher so she could “deal with some issues.”

Los Angeles Police Department investigators have been looking for Fisher for more than a week. Detectives believe he’s in hiding with help from family or friends. They warned that any person found to be harboring him could also face criminal charges.

“We want to get this guy,” said LAPD Det. Frank Ramirez of the abused child unit. “This is a different type of crime. This is what has people so fired up, why people are so emotional and passionate. Because this was just a child.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.