Controlling a classroom isn’t as easy as ABC

Students filed into Chris Cox’s dim classroom at Daniel Webster Middle School in Los Angeles’ Sawtelle neighborhood, took their seats and immediately began working on a language arts warmup exercise.

While Cox took roll, the eighth-graders silently worked. When they went over the answers, students raised their hands and waited to be called on.

Down the corridor, seventh-graders streamed into Brent Walmsley’s classroom and took over. Some sat on table tops; others wandered around the room, pausing to grab foamy handfuls of hand sanitizer that sloshed on the floor.

As Walmsley took attendance, one boy brushed his hair, three girls sucked on lollipops while one sang Pink Dollaz’s “Lap Dance,” and a boy in the last row unleashed a barrage of spitballs. The day’s warm-up was quickly forgotten.

Same school, same day, similar students, similar teachers -- yet profoundly different behavior.

Educators, administrators and experts say classroom management -- the ability to calmly control student behavior so learning can flourish -- can make or break a teacher’s ability to be successful.

‘The hardest skill’

“It is probably one of the things that’s least understandable and most complex about teaching,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers. “This is the hardest skill to master.”

Among the top reasons why teachers are deemed unsuccessful or leave the profession is their inability to effectively manage their classrooms, according to records and interviews.

Many California teachers who were fired and contested termination to a state panel were cited for poor classroom management, among other issues, according to a Times analysis conducted last spring.

In October, U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan slammed American teaching colleges for doing a “mediocre” job preparing teachers, particularly in how to manage a classroom.

Duncan’s complaint is not new. Study after study confirms the importance of classroom management.

But unlike teaching calculus or chemistry, there is no single best practices method for managing a classroom. In fact, there are many, and pedagogical debates abound about what works best. Some teachers, for example, offer rewards for good behavior; others believe that creates a false motivation.

“A lot of new teachers particularly feel frustrated . . . because there isn’t a recipe book that says this is what’s going to work that will work all the time,” said Karen Symms Gallagher, dean of the Rossier School of Education at USC.

Although there are myriad approaches, experts agree on a handful of guidelines: Teachers must be consistent in their message and consequences, lay a strong foundation of expectations early in the school year, follow through with promised punishments when children misbehave and remain dispassionate and unflappable.

Some will have an innate ability to run their classrooms, others will struggle their first years. No one can predict how they will fare until they are given the keys to their first classroom.

“No matter how much you do in teacher preparation, brand-new teachers wish you had more of it because when you’re out there on your own, it’s always different with your own students,” said Beverly Young, an assistant vice chancellor at the California State University system, which trains 55% to 60% of the state’s teachers.

In California, teachers are required to learn about classroom management in their training. The instruction varies among programs, partly because there is no one right method.

At Cal State L.A., professor John Shindler’s 10-week class for those seeking to teach secondary grades covers techniques as well as underlying behavioral theory. Students must also complete 60 hours of classroom observation and 10 weeks of full-time student teaching.

Nearly all of his students said they were anxious about how they would ensure that their pupils behave.

There is widespread recognition that young teachers need support once they enter the classroom. California spends more than $100 million annually on a mentoring program for new teachers.

Last year, more than 27,000 teachers participated. And local administrators, including Webster Principal Kendra Wallace, are paying more attention to beginning teachers’ needs.

When she became principal in 2004, the campus was in disarray. There were four or five fights every day. Students aimlessly wandered the campus.

Wallace made sweeping changes that have raised morale, and test scores have slowly improved. But the increased duties also prompted several veteran teachers to leave, creating vacancies that were filled by inexperienced teachers.

Wallace realized that although some had an innate ability to manage their students, many needed help.

Students must “understand first and foremost that you care about them, but that you mean what you say,” she said.

“If you say the next person who talks in class will be set on fire and rolled down the hallway, you’re in trouble if someone talks and you don’t set them on fire and roll them down the hallway.”

Mentoring teachers

Wallace created a mentoring program for Webster’s young teachers that has grown increasingly sophisticated each year. She also urges new teachers to observe veterans at work and will pay for a substitute to watch their classrooms.

Webster’s mentoring program is led by Chris Cox, a 6-foot-5 English teacher who commands respect in his classroom through a combination of clear behavioral expectations and automatic consequences for failing to meet them.

“None of this is by chance,” he said.

Cox believes in the broken-windows theory of police work: that if small transgressions go unchecked, larger problems will arise. So from Day One, misbehavior is dealt with quickly and dispassionately. Students who get out of their seats without permission, swear or talk back are instantly countered with detentions, phone calls home or trips to the principal’s office.

There is little leeway, especially in the beginning of the year, when Cox gives out dozens of detentions.

“You have to compel compliance,” he said. “The trick is not to be personal: This is the rule; this is the consequence.”

Good behavior, his theory shows, becomes so routine that precious minutes are not wasted every day dealing with discipline.

Cox was not always so successful. He recalled working as a substitute teacher in a science class at Mark Twain Middle School in the Mar Vista neighborhood of L.A. that devolved into a crayon fight. As students took cover behind their desks and threw crayons at one another, Cox stood in the middle of the room getting pelted and repeating what he had learned in his teacher training: “Children, return to task.”

“It was a disaster,” he said. “I got annihilated.”

A veteran teacher took Cox under her wing and told him to place his teacher textbook in a drawer, forget about the paperwork for the first week of school and focus solely on rules and procedures. It worked, and Cox has followed that advice ever since.

Testing boundaries

The middle-school age group, from 11 to 14, is considered by many to be the toughest to teach. Some students are still carrying stuffed animals to class and some are dating for the first time. They tend to test boundaries and question authority, educators say.

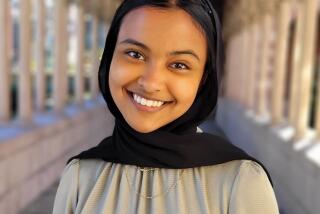

Bryanna Small embodies this challenge. The 13-year-old is well-known in Webster’s front office. She recently spent a period there because she had pierced her face. She is smart, blunt and articulate, with bright eyes and a large smile; she is constantly surrounded by girlfriends.

In first-year teacher Linda Khvu’s class, Bryanna fidgets and talks to classmates when the teacher is not looking, but she also seeks her approval. During one class, she drew on her backpack until Khvu walked by and said stonily, “This is not art class. It’s math.”

Bryanna said she tries especially hard to behave for Khvu because the 22-year-old teacher is nice and explains hard concepts.

“I get distracted, but I catch myself,” she said.

The teacher who has most drawn her ire is Walmsley. Bryanna said he singles her out for misbehaving even though many of her classmates are also talking out of turn and unfocused.

“Whatever you give to me, I’ll give it back,” she said. “If you disrespect me, I’ll disrespect you back.”

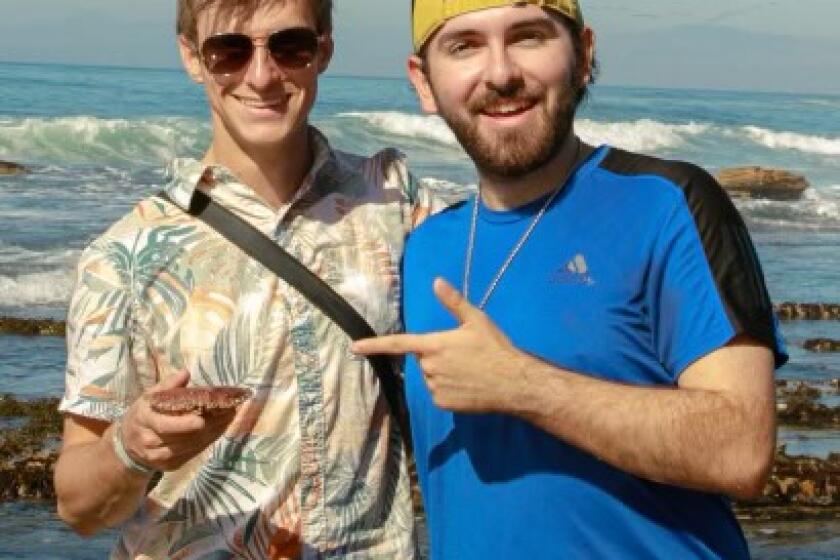

Walmsley is a first-year teacher, an affable and warm man who cares about his students. A Teach for America teacher, the 28-year-old earned a seminary degree and previously worked as a chaplain at a juvenile detention center.

Walmsley tries to relate lessons to students’ lives, integrating popular culture references to help them connect to literature. His enthusiasm is palpable, and he showers them with high fives when they master a difficult concept. But his inability to control some students’ behavior means many minutes of learning are lost each class. Cox and Wallace have been trying to help him better focus his students.

“It’s challenging,” Walmsley said, noting that both he and the students are figuring out their relationship.

During group work, Bryanna is having a tough time sitting still. It’s the last class of the day, and as the minutes to the bell tick by, she wanders around the room, chats with friends and ignores Walmsley’s requests for cooperation.

“How about you be quiet for the rest of the period and let us enjoy it?” Bryanna says as he tries to redirect students’ attention.

Walmsley has finally had it, and he orders her to stay after class. But before the bell rings, Bryanna and another student take off. By the time the teacher reaches the door, the girls are out of sight.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.