Dialysis dilemma: Who gets free care?

Roughly 2,000 times over the last 17 years, Marguerita Toribio, an illegal immigrant from Mexico, has climbed into a cushioned recliner for the three-hour dialysis treatment that keeps her alive.

She has never seen a bill.

U.S. taxpayers have covered the entire cost of her treatment in California: more than $500,000 and rising, not including a kidney transplant in 1993.

The kidney failed when Toribio briefly moved to North Carolina, which refused to pay for her anti-rejection drugs. She needed to go back on dialysis three days a week to clear toxins from her blood, but North Carolina didn’t cover that either.

The best a social worker could offer was a prepaid plane ticket back to California.

“When I came back here, I said, ‘There is no way I’m leaving for another state again,’ ” said Toribio, now 29, before a technician poked two needles into her arm at the St. Joseph Hospital dialysis center in Orange.

Health services and other benefits available to illegal immigrants can vary by the state. Welfare, prenatal care or in-state college tuition might be available in one place and inaccessible across a state line.

The disparities reflect the nation’s conflicting attitudes toward its estimated 12 million illegal immigrants. With limited federal guidance, states often are left to make their own decisions, frequently shaped by political winds.

Dialysis offers a striking example of the dilemmas -- and the occasional absurdities -- that result.

The number of patients is not large. In California, illegal immigrants account for about 1,350 of the 61,000 people on dialysis. Their treatment cost taxpayers $51 million last year.

But dialysis stands out because it is often a lifetime commitment. The investment in a single patient over time can easily top $1 million.

Many states draw the line at illegal immigrants. But officials in California, New York and a few other states figure that not treating patients whose kidneys are failing costs more.

That is because patients without regular dialysis frequently end up in emergency rooms, on the brink of death. At that point, federal law requires that they receive dialysis until they are stable enough to be released -- usually only to deteriorate again within weeks and return to the ER.

It’s like “rescuing a person from drowning, giving someone a good meal and then pushing them over the side,” said Dr. Laurence Lewin, a kidney specialist in Orange County.

Repeated rescuing not only threatens patients’ long-term health, it generally costs more than routine care, some experts argue. In Texas, where illegal immigrants generally can’t get routine care, some have cycled through the emergency room at El Paso’s Thomason Hospital more than 100 times for life-saving dialysis, said kidney specialist Dr. Azikiwe Nwosu.

Such patients are at increased risk of heart attacks and infections.

“Its heartbreaking,” said Dr. Claudia Zacharek, a kidney specialist who until recently worked in Galveston, Texas. “Your hands are tied.”

In grappling with what services to provide for illegal immigrants, some states tip toward the need to care for the sick. Others see free healthcare as a de facto endorsement of their presence.

Congress tried to establish a balance. In 1986, it barred illegal immigrants from the federal health benefits generally available to the poor, with one notable exception: emergencies. The federal government agreed to share the cost of caring for poor illegal immigrants through state-run Emergency Medicaid programs.

The problem is that the federal definition of an emergency is open to interpretation: an acute condition that, without immediate care, would seriously jeopardize a patient’s health or impair bodily functions, parts or organs.

When does an emergency start? When does it end?

Debates have flared over chemotherapy, life-support and dialysis. In 2002, Arizona Sen. John McCain, the Republican presidential nominee, cosponsored a bill to provide dialysis and other chronic care needed to prevent expensive ER visits.

It failed. What’s left is an ambiguous policy that the federal government itself has struggled to clarify.

“We do not pay for chronic care for illegal immigrants,” Mary Kahn, a Medicaid spokesperson, said when asked about the issue in early 2007.

If California and other states were using federal funds to help provide routine dialysis, she said, they were mischaracterizing it as an emergency treatment.

More recently, she acknowledged that the federal government has knowingly been sharing the cost in California for years. It has long been left to the states to decide whether to provide routine dialysis, she said.

Many states, including Texas, Colorado and New Mexico, take the position that kidney failure does not automatically qualify as an emergency because patients can survive for weeks without dialysis before toxins accumulate to fatal levels.

Other states have wavered. North Carolina, for example, now provides routine dialysis for illegal immigrants. Conversely, the Georgia Medicaid program stopped paying for dialysis in 2006 amid rising sentiments in the Legislature that illegal immigrants were a financial drain.

“Georgia ain’t California or New York,” said Mark Trail, head of Georgia’s Medicaid program until last month, noting a strong conservative tradition.

The courts haven’t cleared up the issue.

A group of illegal immigrants sued Arizona in 2002 after the state attempted to cut off their dialysis. Heeding arguments that sporadic emergency treatments would jeopardize lives, a judge told the state to keep treating them while the case was decided. In a settlement last year, the state agreed to restore its policy of providing routine dialysis, but the settlement applies only to Arizona.

California’s dialysis policy is largely an economic calculation, said Stan Rosenstein, the administrator of Medi-Cal, the state healthcare program for the poor that covers dialysis for illegal immigrants.

The cost of one routine treatment is about $250. The cost of providing it in the emergency room can easily climb into the thousands of dollars, especially if the patient has to be admitted to the hospital.

To advocates of stricter immigration controls, such comparisons miss the point.

“Taxpayers are on the hook for people who aren’t supposed to be here,” said Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies.

The fear in many states is that offering routine dialysis will simply lure more sick people from other countries.

“We cannot provide dialysis to the world,” said Ramiro Valdez, a Dallas social worker and medical consultant.

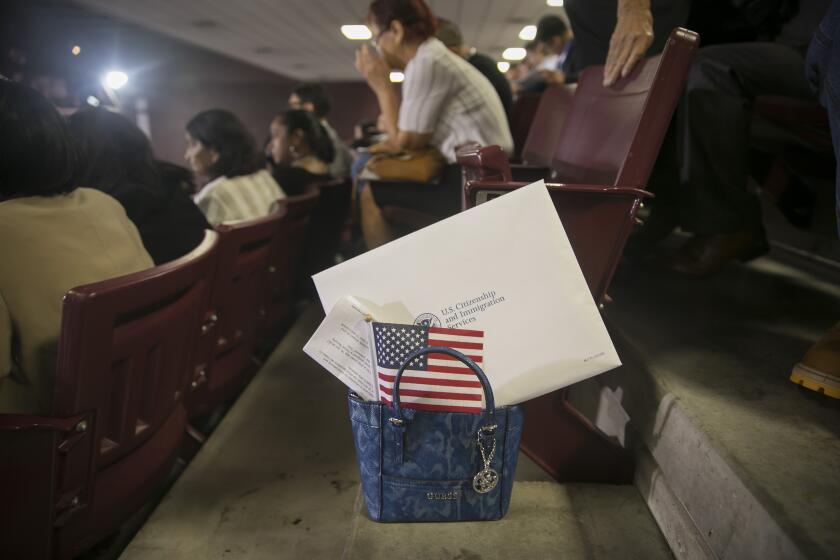

Teresita Aquino, an illegal immigrant from the Philippines, hadn’t intended to stay in the United States, but being rushed to the emergency room with kidney failure eight years ago changed her mind. Now, a free transportation service picks her up three days a week for her dialysis in Torrance.

“If I go home, I won’t be able to afford this,” said Aquino, 56. “No way am I going home.”

In general, however, California’s recent experience does not suggest that free routine dialysis will become an open invitation to illegal immigrants with kidney failure. The number of undocumented immigrants on government-funded dialysis jumped from 835 to 1,327 between 1998 and 2001 but has remained fairly steady since.

Social workers and doctors in Texas and other states said patients may be vaguely aware of the services in California, but they are often too sick to move by the time they understand the gravity of their plight.

Some hospitals in Texas quietly encourage illegal immigrants to move to Houston, where the public hospital district uses local taxes to pay for routine dialysis even though the state Medicaid program does not.

Dr. Karla Vital, a kidney specialist at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, said her hospital encourages Mexican nationals to return to Mexico. Some hospitals pay for plane tickets back.

Mexico offers dialysis to those who can afford it, but access is far more limited for the poor.

Delia Lopez, a 42-year-old illegal immigrant who recently started dialysis in Los Angeles, said she would rather be with family in Mexico. But she can’t afford the treatment there, she said.

“I have friends who have died because of lack of dialysis,” said Lopez, a longtime diabetic who arrived in the U.S. four years ago while her kidneys were still functioning.

The only alternative to dialysis is a kidney transplant, a procedure California and a few other states provide to illegal immigrants. Last year, 52 of the 1,912 kidney transplants in California were for illegal immigrants.

Several studies show that a transplant pays for itself in three dialysis-free years. Critics, however, say that dipping into the organ pool is a greater outrage because so many citizens are waiting.

“It’s not like you go to Costco and pick up a kidney,” Krikorian said.

Toribio is now seeking a second transplant.

She said she is grateful for the care she has received in California. But Toribio, who works in a textile factory for $8 an hour attaching tags to blankets, towels and bathmats, believes the United States should accept it as the price of a cheap labor pool.

As much as she would like to visit her parents and grandparents in Mexico, she has never returned.

It is not worth the risk of leaving California: She might not be able to get back.

--

anna.gorman@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.