A dream home in Palos Verdes Estates deferred

It had been the dream of a local surgeon: a gray, spaceship-like structure with floor-to-ceiling windows and a facade that jutted out toward the Pacific Ocean.

“I don’t want a big square house like that one,” Dr. Louis Moore reportedly told the architect, pointing to a neighbor’s home during a drive around Palos Verdes Estates. And so, in 1958, an avant-garde, five-bedroom home with angular appendages was completed on the cliff above Malaga Cove.

Now the current owner wants to build his own dream house. But unlike Moore, Mark Paullin envisions something that echoes the Mediterranean aesthetic that abounds in the affluent coastal community.

However, Paullin’s plans to raze the Moore house have been in limbo since preservationists demanded the city explore the building’s historic value. It was Lloyd Wright — the son of Frank Lloyd Wright — who had listened to Moore’s demands and designed the futuristic residence. Although the younger Wright never received the same acclaim as his father, historians say his work deserves protection.

But Paullin, who grew up in the area and still surfs the local breaks, said the home has long been viewed by residents as an oddity, not a landmark. And although he had heard of Lloyd Wright, he didn’t know the significance of the architect’s work. Before he bought the property in 2004 for about $2.5 million, Paullin inquired about restrictions on demolishing the home with both the city and the homeowners association. Neither had previously stood in the way of bulldozing a building because of its lineage.

“I thought that I’d be welcome to build a home that would be more in keeping with the neighborhood,” said Paullin, who owns a manufacturing company. “I’m not a developer; I’m not trying to get rich. I’m just a regular guy from the area. We didn’t just walk in and say, ‘Let’s knock this thing down and build ourselves a McMansion.’ I bought it to build my own home.”

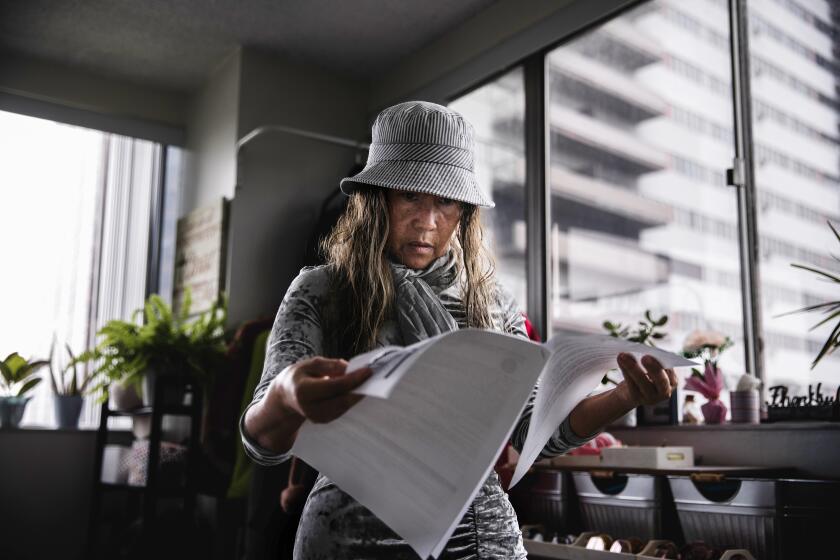

Paullin, 60, and his wife, Barbara, moved out of the house about three years ago, thinking their plans would be approved and construction would soon begin. The Moore house, they felt, was poorly designed. It had rooms with low ceilings that failed to take advantage of the view and natural lighting. It suffered from mildew, poor drainage and was not earthquake safe. The Paullins’ new home would be energy-efficient, have spacious rooms that opened to the sea and allow for an expansive backyard featuring a garden and a pool big enough for their four children and friends.

The first blueprint was rejected because it would block neighbors’ views. In the exclusive, cliff-side community where one pays for the majestic ocean view, Paullin believes the proposal “stirred the hornet’s nest a bit” and led to someone tipping off the Los Angeles Conservancy that a piece of noted architecture was about to be lost.

Hundreds of letters opposing the demolition have since been mailed to city officials who then ordered a study to assess the historical value of the Moore house.

“I think people in general are just tired of seeing perfectly functional, historic treasures needlessly destroyed,” said Michael Buhler, director of advocacy at the conservancy.

Buhler said the scenario could have been prevented if Palos Verdes Estates had preservation laws, which are lacking in more than half of the cities in L.A. County.

A wealthy community of 13,500, Palos Verdes Estates is made up of a maze of roads overlooking the Pacific. Most of the homes are multi-level, rectangular and feature red tile roofs. All exterior alterations must be approved by the city as well as a committee that reviews the aesthetics of proposed buildings.

Paullin has offered to donate the Moore house to several organizations, and even offered to pay the moving costs. None have agreed.

Some residents believe Paullin has been put in an unfair position.

“That house has always been a laughingstock, it’s almost an embarrassment,” said Pat Vancura, 64,who lives on Paullin’s block. “In all the years the house was there, no one raised a flag, no one came and discussed it and said ‘Let’s try to get a historic designation for this.’ Now Mark’s stuck with a house he paid full price for that he can’t do anything with.”

City officials say they’ve found themselves in new territory, having never before dealt with protests over historic property, and need to tread carefully.

“We’re simply doing what we’re required to by our process and by state law,” said Allan Rigg, director of city planning. “We’re not subjecting him to anything that’s outside of those two requirements.”

Architecture critic and author Alan Hess said Lloyd Wright’s contributions have often been diminished because of his father’s imposing shadow. “His whole life, he never received the recognition he deserved,” Hess said. “His father had a more dominating persona and people went to him because they wanted a Frank Lloyd Wright house. Lloyd Wright really was much more considerate of his clients and their lifestyle.”

For Eric Lloyd Wright, 80, the home will always remind him of a time when he and his father worked side by side. A third-generation architect, he helped craft the Moore house and still marvels over his father’s design.

“It is, I think, one of his best,” he said. “It will be a great loss if that house is removed and another large box is put in its place.”