Pasadena steps up effort to acquire historic YWCA building

A lavish hilltop estate boasting 165 rooms, an ocean view and a palatial pool fit for a publishing magnate would end up her most famous work.

But Hearst Castle was just one of hundreds of buildings designed by Julia Morgan, believed to be the first female architect to practice independently in the United States. And although she had a flair for opulence, Morgan dedicated much of her time to projects intended for working-class women.

It was Morgan who conceived the three-story YWCA building with the red-tile roof and arched windows on Marengo Avenue in Pasadena. Built in 1921, it became integral to the Civic Center established during the ambitious City Beautiful Movement, an architectural era in which grand public structures were embraced as essential ingredients to a community’s success.

But after a wealthy Hong Kong businesswoman bought the property 14 years ago, the refuge that once offered patrons a swimming pool, gymnasium and library deteriorated into a dusty, hollow version of Morgan’s vision. Blemished by peeling paint, water damage and boarded windows, it sits in the shadow of Pasadena’s distinctive City Hall.

Frustrated by its declining condition, city officials voted last week to use eminent domain to claim the structure. The motion came six months after the owner rejected the city’s offer to purchase the property for $6.43 million and countered with a figure nearly double that amount.

In a community that has aggressively preserved its architecture, residents familiar with Morgan’s work are applauding the city’s decision to wrestle the building from its owner.

“It’s a necessary step,” said Dave Gaines, 57, a member of the preservation group Pasadena Heritage. “That building’s going to deteriorate fast. It’s just sat idle and the owner is not maintaining the inside.”

But the attorney for Angela Chen Sabella, whose company Trove Investments bought the property for $1.8 million, rejected claims that his client stood by as the building slid into ruin.

Greg Perry said Chen Sabella, who studied architecture at USC, loves the building and has an appreciation for Morgan.

“She has not sat there and let the building rot,” he said. The building came with wiring, heating and plumbing problems. Plans to open a boutique hotel fell apart. And then the recession hit.

About six years ago, Perry said, the city offered to buy it for $750,000, which he considered a lowball attempt. Chen Sabella, who owns several buildings in California, instead hired developers and architects and looked into converting the structure into a hotel or condominium complex.

“When you start to pencil everything out and make this a viable project, where the partners would make money at the end of the day, it didn’t work because of all the preservation you had to do because of the historic nature,” Perry said. The attorney declined to grant access to the building, but confirmed that photos shown at a City Council meeting depicting broken skylights and standing water were accurate.

Those details are what pushed the city to turn to eminent domain, which allows government to force the sale of a piece of property for public use.

“We reached the conclusion that the owner was not able or willing to pursue the care of the building and its reuse,” said Pasadena Mayor Bill Bogaard, whose wife helped found Pasadena Heritage. “After years of effort and no progress, the city is taking the next step.”

Bogaard said that the council is open to discussing the issue further with Chen Sabella, but that she’s lost credibility when it comes to taking action.

Pasadena will probably have to file a lawsuit to take possession of the building, and Trove Investments could then challenge the city’s right to acquire the property. A price would be determined by the court.

“The city has not assisted us in coming up with a direction or project for the property and now they are coming to try to take it away,” said John Peterson, an attorney for Trove who specializes in eminent domain cases. “I think they have an agenda for the property that does not include a private owner.”

If the building is handed over to the city, its first task would be staving off decay, which could cost more than $100,000, officials said.

Interestingly, Morgan was never driven by large sums of money, said architectural historian Mark A. Wilson, who wrote “Julia Morgan: Architect of Beauty.”

“Her whole career she was dedicated to doing those buildings and she did them for nominal fees,” he said.

A petite woman known for her Mediterranean style and love of Spanish missions, Morgan received an engineering degree from UC Berkeley and was the first woman to graduate from the architectural program at Paris’ famed Ecole Des Beaux-Arts.

Morgan became affiliated with the YWCA when her client Phoebe Apperson Hearst, a YWCA advocate, recommended her to the women’s organization. At the time, the group was undergoing a rapid expansion to meet the needs of a burgeoning but poorly paid female workforce. Among her 720 designs, Morgan created about a dozen YWCAs, as well as shelters, clubs, hospitals and centers geared toward women.

At the same time, she was hired by Hearst’s son, publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, to create his massive castle. For nearly 30 years, Morgan rode a train every week from San Francisco to San Simeon, designing rooms inspired by furniture the mogul had purchased in Europe.

“Her buildings are so well designed, so carefully thought out and well constructed that they stand the test of time. The structures tend to hold up better than most of that time because she was trained as an engineer,” Wilson said. “William Randolph Hearst treated her with the utmost respect, and as an equal.”

The former YWCA building in Pasadena may be a far cry from the flash of Hearst Castle, but resident Milad Sarkis says it offers valuable insight into Morgan’s work.

“It was designed as an institutional place, but it’s still residential in feel,” said Sarkis, 26, who made the building the subject of his architecture graduate school thesis. “It’s beautiful and grand, but it’s not about pomp and circumstance. It’s very much a working building that was built elegantly.”

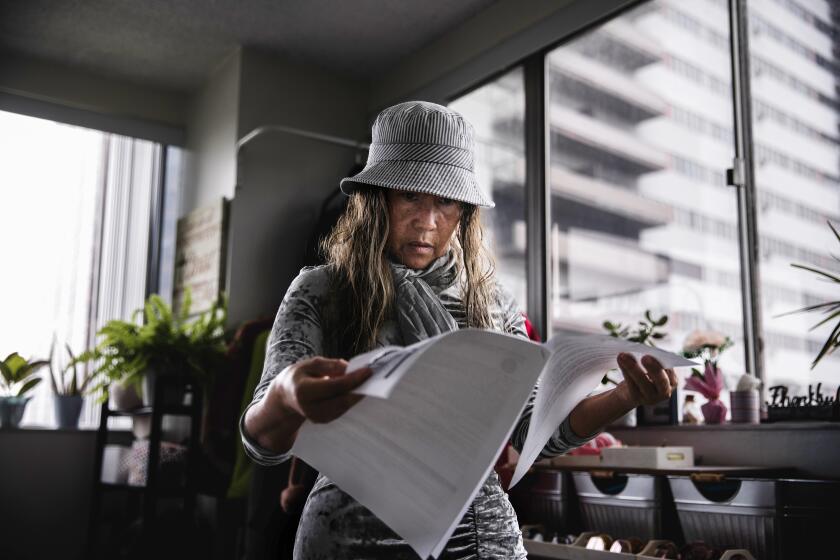

After spending two years poring over old photos and floor plans, as well as researching the history of the building and its creator, Sarkis was disheartened when finally allowed to see its spoiled insides.

“You see what it was, you see what it could be and then you see what it’s not,” he said. “The building can only stand so long without maintenance before it will eventually collapse.”