Towers of Power

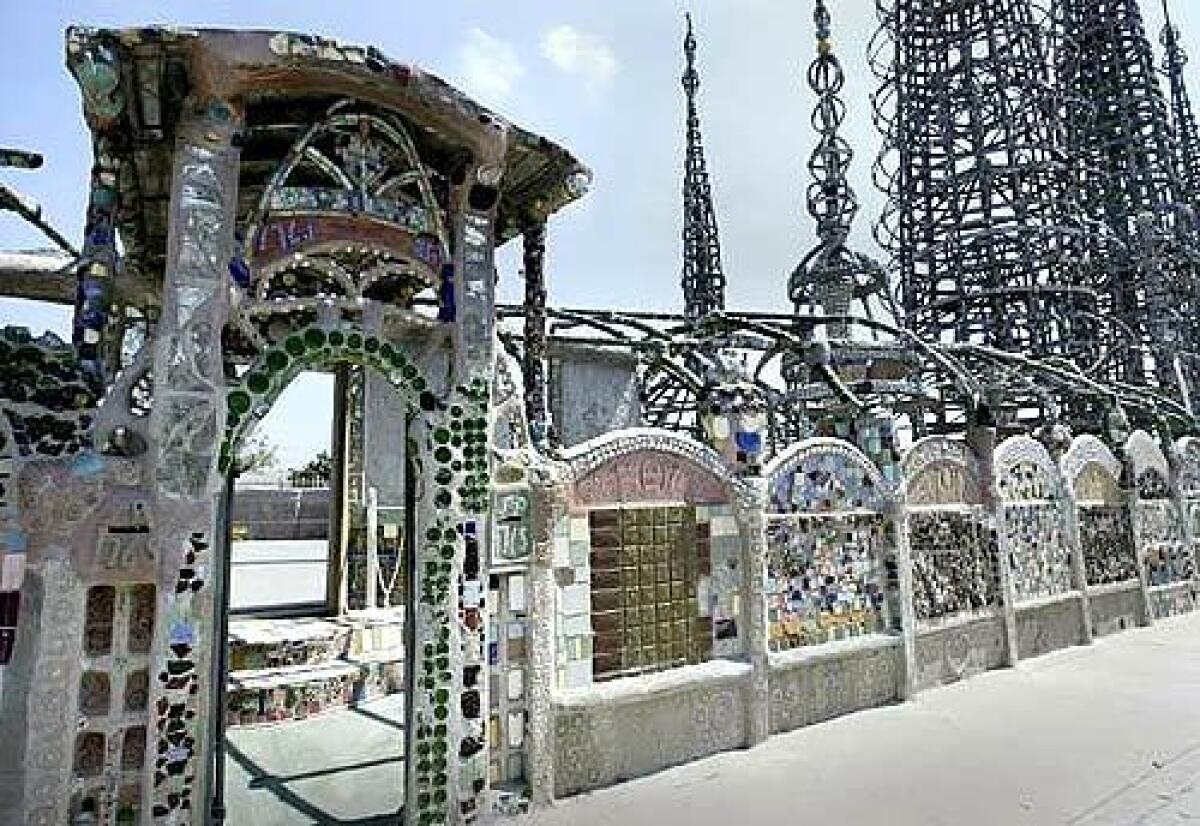

Watts towers did not begin with a tower at all. It began with a ship, or an utterly immobile rendition of one. Three thousand miles from the ocean that carried him to the United States from Italy 26 years before, Simon Rodia dug a boat-shaped trench at the narrow tip of his triangular lot, filled it with concrete and anchored into it scavenged lengths of steel. He constructed a knee-high, green-tinted concrete deck, which he decorated with salvaged tiles in sky blues, ocean greens, and sunset yellows, oranges and pinks. He wrapped the exposed steel rods in chicken wire and coated them with cement mortar. He embellished the tallest one—the foremast—with a series of delicate openwork ovoids. The aft mast became a succession of bowl shapes covered with white seashells.

With that, Rodia embarked on a 34-year voyage of sculptural whimsy around his tenth-of-an-acre backyard. Those who study the Watts Towers say he had no formal plan. Yet in that first sculpture—later christened the Ship of Marco Polo—lies the template for the entire work: the spires, the tiles, the juxtaposition of concrete with capriccio. Indeed, some students of the towers say Rodia conceived of the site itself as a seafaring vessel, setting what looks like a captain’s wheel into the base of the eastern tower, just behind the Ship of Marco Polo.

Rodia’s tools were crude: a pipe-fitter’s wrench, a chisel, a mixing pail. He worked without machine tools or drills, without scaffolding or bolts. It was an obsession that consumed him through six presidents, two earthquakes and a world war, until he had single-handedly constructed, in addition to the ship, three tall towers, a gazebo, a fountain, a fish pond, two enclosure walls and various other things—17 sculptures in all. The tallest tower rises more than 10 stories above the flat Central Los Angeles landscape. The entire agglomeration, considered as a single work, is said to be the largest structure ever made by one man alone—a vertical triumph in a horizontal town.

In 1955, Rodia handed the deed to the property to a neighbor and walked away. He left it to us to figure out what to do with what he had made. Fifty years later, we’re still scratching our heads.

By training Rodia was neither artist nor architect—he was a cement finisher and tile maker who could barely read. But he is admired among artists for his superlative grasp of color, among architects for his deft reliance on curved forms, and among engineers for his creative manipulation of concrete, applying homemade batches of it in a “thin shell” style that was rare at the time but is widely used today in building construction. Rodia’s real genius, though, was in transforming the mundane and familiar, the mass-produced and commonplace, into something unlike anything else, something singular and surprising and strange. “Go anywhere in the world and look for a structure that’s built like the Watts Towers,” says Bud Goldstone, a structural engineer who tended to the towers under various city contracts for two decades. “There is absolutely nothing like it. It is unique.”

Over the years the towers have been alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) puzzled over, celebrated, vandalized, admired and nearly demolished. Now they are mostly left alone, looked after by a caring few and overlooked, ignored or forgotten by the rest. Watts Towers is one of just six national historic landmarks in Los Angeles (San Francisco has 18, New York City 85). Yet from June 2004 to June 2005, only 6,500 people showed up for tours, compared with 30,000 at Pasadena’s Gamble House and 690,000 at Hearst Castle. “L.A. has a very twisted view of the arts,” says Edward Landler, who with Rodia’s grand-nephew Brad Byer recently completed “I Build the Tower,” a documentary film project 20 years in the making. “You’ve got to be accomplished. You’ve got to be ‘special’ to be taken seriously. Here is this man, this uneducated man, this dirty man who you wouldn’t pay attention to on the street, who created this thing that can touch us in this way. He didn’t care to show himself off, but he wanted to be remembered. He had no notion of this as art—he just wanted to build something.”

Why aren’t we invested in this phenomenal achievement? Why don’t we honor Rodia’s vision and perseverance, this classic tale of a poor immigrant making his way to the promised land, creating something from nothing, then moving on? In this most transient of towns, why aren’t the towers featured on the Los Angeles city seal? “The reason why they don’t try to make a cultural icon out of it is because of the people who live in Watts,” says Cecil Fergerson, who rose from a childhood in Watts to become a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and whose face is featured in a mural at the Watts Towers Community Arts Center. “It’s a community of poverty,” Fergerson says. “Always was. When they take care of that problem, the towers will be bigger than the Statue of Liberty.”

Unlike most public art, the watts towers cannot simply be stumbled upon. They’re located on a dead-end street, and you don’t go there unless that’s exactly where you mean to go. A sign on the 105 Freeway helps uncertain visitors find their way, but there is no sign on the 110, “the one people use,” says Councilwoman Janice Hahn, whose district includes Watts and who has been struggling with the Caltrans bureaucracy to get one put up. “People need all the help and encouragement we can provide, and we’re not doing our part.”

The vast majority of visitors don’t even attempt to drive—they arrive by climate-controlled tour bus in search of the exotic and dangerous, says Linda Campanella, who works at the adjoining arts center, which runs tours of the towers. “We get people from Japan, Australia, a lot of Europeans,” Campanella says. “Some of our out-of-towners, they come here and they say they want to know what the deal is about Watts, this wild place they’ve been hearing about all their lives. The towers give them an excuse to have a look around.” Tramell Turner leads tours of the towers. Turner, who is 27 and an aspiring actor, was born in Watts. The question he hears most often from visitors, he says, is: Where are you from? “They want to know if I’m really from Watts,” he says. “Then they want to know what that’s like. I tell them it’s poverty, that I’d move to Beverly Hills if I could.”

There are many, many people living in Los Angeles who have never been to the towers, says Rosie Lee Hooks, director of the arts center. More than a few of those people live in Watts. Part of the indifference may be due to a cultural disconnect—the towers have long been a symbol of African American pride in a community that now is more than half Latino. Another problem is fear. “We have 16 to 20 gangs within the area that is Watts,” Hooks says. “People do not feel safe moving from one block to the next. It’s a constant struggle.” For all but the most intrepid urban explorers, the notion of seeking out the towers holds little appeal. “We’re below the Mason-Dixon line. The only real attention Watts gets from the city is from the police,” Hooks says.

The line between the streets and the towers is often a tenuous one. John Outterbridge, who was director of the arts center for nearly 17 years, says he urged kids on their way to school to deposit their guns at the towers. “The Crips and the Bloods, I saw a lot of those kids grow up,” he says. “I said, ‘Leave your guns with me, if you’ve got to have them.’ ”

Five years ago Zuleyma Aguirre, the head conservator at the site, was attacked early one morning in the parking lot. A security guard patrols the site night and day, but he did not happen to be watching the lot when a youth on a bicycle swooped in, smashed his fist into Aguirre’s jaw and grabbed her purse. He broke six of her teeth and tore open her lip. She’s had three surgeries to repair the damage. “I’m a survivor,” she says. “It’s been very hard to come back here every day, but I am honored to work here. This is my cathedral.”

By all accounts the arts center has proved to be a crucial local resource, particularly by providing a haven from the streets for at-risk youth. But over time its mission has become too narrowly focused on the immediate community, to the exclusion of sustaining interest in the towers themselves, says Seymour Rosen, who was an early supporter of the towers and now runs SPACES Institute, an art preservation archive. “When you go into the center, there are no books on outsider art. There is no larger context for the work,” he says. “There is very little that would be of interest to the outside world.”

Margie Reese, general manager of the city’s Cultural Affairs Department, which leases and operates the state-owned towers, says that’s as it should be—for now. “My frustration is explaining to people that Watts Towers as a tourism destination right now is a fallacy,” she says. “Once I’ve taken the tour and seen the glamorous towers, I’m still curious. I want to know about the community that surrounds this icon. In my mind the story is unfinished.” There is very little to appeal to outsiders, Reese says, and much to be concerned about. “When I drive to Watts and get off the freeway, immediately I begin to think about the people who live here,” she says. “It’s difficult to look at a tourism component without looking at the needs of the community.”

Though engineers marvel at the steadfastness of the towers, time and the elements present formidable challenges. At any given moment the sculptures are riddled with cracks. It takes a conservation crew of 11 to address the fissures and fractures caused by the everyday stresses of the harsh Southern California sun. During the heat of the day the steel armatures expand, and in the cool of the night they shrink. The cement mortar shells are not as flexible, so all that internal motion causes hairline cracks, thousands of them. When moisture gets into the cracks, the problem worsens. Then there are the perennial crises, such as last spring’s incessant rain, last winter’s freak hailstorm and eight earthquakes in seven decades, most recently the 6.7 Northridge quake, which caused such extensive damage that the towers were scaffolded for years.

Vandalism also has taken a toll. In the decades before full-time security, neighborhood kids would root around looking for anything of value and use the gazebo for target practice. Graffiti is scratched into some of the tiles, and hundreds, if not thousands, of shells and bits of tile and glass are gone for good. An estimated 40% of the decorative surfaces have been repaired or replaced, a job that requires a delicate balance between preservation and re-creation. “It’s like dentistry,” says Melvyn Green, a structural engineer who oversees the work. “When you have a cavity you go to the dentist, he drills around, gets rid of the debris, the loose stuff, the rot, and then he fills it. That’s what you see here at the towers.”

That kind of upkeep comes at a price, and every city budget cycle seems to bring another scramble for funding: Will there be money for tours? For annual events such as the Jazz Festival and Day of the Drum? To fill the recurring cracks, to replace the constantly falling tiles? Every year the revenue is found—often in state and federal disaster grants—and the towers drift along to face another season of uncertainty. One thing seems certain, however: The towers are viewed as a drain on city funds, never as a viable source of income and pride.

In 2000, as the city celebrated the new millennium, John Outterbridge looked on in frustration. “The whole thing focused on the Hollywood sign as an emblem of the city,” he says. “That was a real failure. I would have fought for a focus on Watts Towers, this city’s Eiffel Tower. We should have had all-night jazz, a red carpet, a grand tented party. Every spotlight in the city should have been on the towers. Think of it. Think of what that would have meant.” But the city does not take itself—or its history—seriously enough to make the towers a priority, Outterbridge says. “As far as I’m concerned, it has a lot to do with a metropolitan region that does not recognize its role as a cultural mecca and force. There’s not a lot of romance here in this city.”

The annual budget of the city’s Cultural Affairs Department—which was nearly eliminated in 2004—is about $9.5 million. In New York it’s more than 10 times that. “In Los Angeles, we don’t recognize the value of what we have,” Outterbridge says. “We got rid of the Red Car. In San Francisco, people come from around the world to stand next to the cable car. It’s more than transportation. It’s the pulse of romance.” Even the entertainment industry—which is quick to remember the Watts Towers when it needs something to blow up, as in the film “Colors,” or a backdrop for extreme violence, as in the video game “Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas”—has shown little sustained interest. “There’s no relationship,” Outterbridge says. “I hosted many movie shoots at the towers. They spend more money on some of the premiere parties than the entire towers budget.”

There has been some outside support. The Getty Conservation Institute occasionally sends conservators to the site to observe preservation techniques and offer advice. But that is not enough, says Tim Whalen, director of the institute. “To drive down to see the towers, for people who live in L.A. or for people from Germany, is an investment of time,” he says. “When you get down there, you can’t get a coffee and you can’t look in a bookstore. It’s those kinds of amenities that cause other monuments to be animated. Those things are certainly missing from the towers.”

Recently, the Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation launched Arts + Culture L.A., a private nonprofit with the sole function of promoting Los Angeles as a destination for cultural tourists. What about the Watts Towers? “I have to be honest with you,” says Laura Zucker, executive director of the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and a consultant on the project. “We have a lot of assets in L.A. We’re not going to be able to concentrate on a handful at the expense of others. I hope all boats will rise.”

One might think, then, that the problem is an intractable one: The keepers of the towers need to create an environment that will attract visitors and make money, but they can’t create that environment without already having money. But Whalen says that’s not quite right. What the towers are missing, he says, is a leader with a strong vision. “Money doesn’t solve conservation problems,” he says. “You can throw money at things, but unless there is leadership, it doesn’t matter how much money you have. Money can only be effective if there is leadership behind it.”

The first railroad line in the county, built in 1869, ran from downtown to the harbor, prompting a mini housing boom in the area near 103rd Street now called Watts, after Charles H. Watts, the Pasadena developer who owned the land. Later, when Watts Junction became the transfer point for travelers en route to Orange County and the South Bay, it was called “the Hub.” Still, there were truck farms, windmills, roosters and lots of open space. Despite its proximity to the ocean and the city, this was the sticks, a semi-wild place where a man could come home from work and hammer and pound late into the night.

Clad in tattered overalls and a dusty fedora, Sabato “Simon” Rodia built his towers at a time when the community was a varying blend of Europeans, Mexicans, Japanese and African Americans. He called his work “Nuestro Pueblo” and, as lore has it, invited neighbors to hold weddings under the gazebo and baptisms in the fountain, and enlisted local school boys to pilfer crockery from their mothers’ kitchens and gather oddments along the railroad tracks.

By the time Rodia left, at age 76, Watts was built up and filled in, and the towers were already a relic, with brightly colored tiles from the defunct Malibu Potteries embedded alongside pre-World War II Japanese porcelain. The towers provide “a visual history of Californian, and American, material culture and decorative arts of the first half of the twentieth century,” wrote Bud and Arloa Paquin Goldstone in a book for the Getty Conservation Institute. They are “a rich repository of elements that have played a part in the life of almost every American between at least 1900 and 1950.”

Through the decades the towers have been many things to many people, very few having to do with the merits of the work itself. In the 1950s, shortly after Rodia walked away, the towers wound up in the hands of a local entrepreneur who wanted to turn them into a taco stand. Where he saw a business opportunity, the city saw a nuisance—a cluster of structures that were unsafe and not up to code, Rodia never having bothered with permits—and ordered them demolished. Bud Goldstone, then a young aerospace engineer, saw a puzzle. He did the math, declared the towers sound, and a “load test” was performed with a hydraulic cylinder and a winch truck. Fortunately, the towers survived, and even became slightly famous as the public descended on Watts to lay eyes on this curiosity. In “Underworld,” novelist Don DeLillo’s sprawling paean to the latter half of the 20th century, one character who visits the towers during that time sees them as “a kind of swirling free-souled noise, a jazz cathedral.” Another character, a sculptor, “didn’t know a thing so rucked in the vernacular could have such an epic quality.” The towers left her feeling a “delectation that took the form of near helplessness.”

All that came to an end in the summer of 1965, when the blood and anger of the Watts riots in an instant supplanted the towers as the area’s central claim to fame. Between Aug. 11 and 17 the rioting consumed 11 square miles, leaving 34 people dead and $40 million in property damage. Soon, however, community leaders began to see the towers as a symbol of healing. Residents and activists built the Watts Towers Community Arts Center, where local artists could showcase their talents and neighborhood kids find an artistic alternative to the streets. “The towers are an embodiment of an aspiration,” says documentarian Edward Landler. “We rise from the dirt, we rise from the mud. Heavy, heavy stuff, tons and tons of material rising so gracefully and lightly, the weight is shed as you rise to the heavens. The towers transcend the rather patronizing pat on the head of calling them ‘folk art.’ You feel differently going in there. You go into the gazebo and no matter how hot it is, there is a sense of cool and calm and stability.”

Yet in bearing the weight of a community in need, in acknowledging its environment and becoming a part of that environment, the towers as a work of art all but disappeared.

It’s tempting to think about moving the towers. But like the Space Needle, Sears Tower or the Hollywood sign, it’s rooted to its place, and derives its beauty and its meaning in large part from that place.

Back in 1959, after the city ordered the towers demolished and before they were saved, a wealthy bureaucrat from the desert development of California City approached Bud Goldstone and offered $50,000 to relocate the towers to his town. “I said forget it,” Goldstone says. “If you want to move this mother, first of all you’ve got about a billion pounds to lift. It’s too much trouble.”

In any case, there are a few glimmers. The state has secured a grant to install an interpretive center at the towers, a place to buy tickets and relax while waiting for a tour, where kids can pick up bits of tile and watch a short film about Rodia. Both the city and state have long hoped to buy up the row of low-slung bungalows across the street, transforming them into artists’ studios, a café, a bookstore. (In today’s overheated real estate market, that’s becoming an expensive proposition. One modest two-bedroom cottage facing the towers was recently listed for $315,000.) Janice Hahn earmarked funds for a $4-million junior arts center, now under construction in the parking lot of the existing community arts center, and is trying to generate support for a movie theater nearby. She sent a letter to Oprah Winfrey inviting her to visit Watts to mark the 40th anniversary of the riots in August, and to help give the community a leg up. “Oprah,” she wrote, “you make people’s dreams come true and the community of Watts needs your help.” She’s still waiting to hear back.

As for a café and bookstore at the towers, Hahn lets out a wistful sigh. “Those are great ideas,” she says. “I love those ideas and I would support them 100%. But when push comes to shove, if you ask people in the community if they would rather have a grand vision for the Watts Towers or would they want to have economic development and good jobs, I’d venture to say they’d opt for the latter.”

But economic development and a vision for Watts Towers don’t have to be mutually exclusive. In the easternmost bungalow on 107th Street, across from the towers, lifelong neighborhood resident Big Al Jordan has just opened Watts Life, a T-shirt and trinket shop that also serves as a tribute to the towers. Jordan, who has worked for Rep. Maxine Waters on economic development and spoken on behalf of the National Urban League, which nurtures African American businesses, doesn’t know anything about a grand vision. What he does know is that people who visit the towers have disposable income and want to take something with them when they leave. He is providing them with that opportunity.

As jazz from a boombox fills the room, Jordan points out several T-shirts of his own design, some with images of the towers, others with verse (“Towers towers large and small, Simon made them for us all”). “Simon Rodia gave us something monumental,” Jordan says. “He said look, if you’re gonna stand for something, at least stand for something. Not for something that’s gonna be hatred or something that’s gonna be tore down. Stand for something that’s gonna be solid.” Above the cash register are photographs of Jordan with recent visitors, tourists from the Netherlands and Germany. “Most times people say this is a handicapped community,” he says. “They say people come in here on one level and move up and out. No. I don’t believe in moving out. I’m about staying and improving. Simon Rodia did that, we can do it too.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.