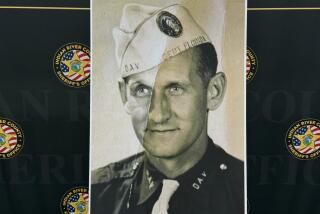

Bataan Death March survivor recalls burials and ‘The Skull’

This post has been corrected. See the note at the bottom for details.

For Dick Cooksley, the nightmares from that most trying and lethal time of his life still linger: slogging through island jungles in the dreaded Bataan Death March, watching as some of his fellow soldiers and friends were beheaded by their Japanese captors.

But Cooksley, now 92 and living in Arizona, survived it all — three long years of enemy captivity in seven different camps.

This week, nearly seven decades after his release, the retired Army captain received long overdue recognition of his suffering: the Bronze Star Medal.

In his understated manner, the old soldier told the Los Angeles Times that he was proud to stand before fellow soldiers and politicians to receive the medal Tuesday in Ft. Huachuca, Ariz.

“It was something I had coming and I finally got it,” he said of the medal, which was presented by U.S. Rep. Ron Barber.

The medal was awarded after a friend of Cooksley’s contacted Barber’s office, saying the Bronze Star Medal should have been presented much earlier.

In the brief but emotional ceremony, Barber said Cooksley’s time in captivity was “a period of cruelty,” lamenting that the former captain had not received the medal during his 20 years of Army service. The oversight was unfortunate, Barber said, saying now it has been made right.

“I hope he [Cooksley] will forgive us for taking too long,” Barber said, calling the honor of bestowing the medal “incredible.”

Cooksley, who lives in Bisbee, Ariz., told The Times about life as a POW, including the death march, which some experts say claimed the lives of 10,000 U.S. and Filipino prisoners of war.

He said he helped bury hundreds of U.S. soldiers a day for a month because of the brutality of the Japanese. Later in the war he and other selected POWs were shipped to Japan to work in various activities supporting the Japanese war effort. He also recalled being on a vessel in a 15-ship convoy, each craft carrying about 900 POWs, most were sunk by American submarines after they left the Philippines; leaving several ships, including his to make it to Japan.

He said the worst time was in a camp led by a Japanese commander the captives nicknamed “The Skull.”

“He liked to chop heads,” Cooksley told The Times. “He made you dig your own grave, then he chopped off your head and kicked your body into the hole. I saw it happen too many times.”

Cooksley ended his captivity in a copper mine in northern Japan.

“Somebody decided to check this out and they found out we had something coming,” he said of his Bronze Star. “I think most of us old World War II POWs are finally getting recognized.”

Cooksley said he retired from the military in 1960, and spent years as an official with the Boy Scouts of America. He said he was proud that as a POW survivor he could testify in the late 1940s against some of the Japanese who were found guilty of maltreating American POWs.

Being a soldier runs in this family, he told The Times. His father served in World War I and his three sons served in Vietnam, Cooksley said.

Asked how he survived those cruelties of so many years ago, Cooksley said: “It just wasn’t my time.”

For the record, 6:48 p.m. Sept. 7: A previous version of this post said it had been nearly six decades since Cooksley’s release. It has been nearly seven decades. The post also said that the death march claimed the lives of 10,000 U.S. service members. The dead included both U.S. and Filipino prisoners of war.

ALSO:

No charges for D.C. officer for alleged threat to first lady

Fluoride: Portland City Council poised to back water treatment

Kellie Pickler’s shaved head: Cancer patients get the message

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.