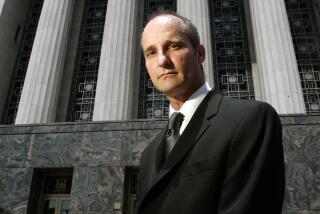

Merrell Williams Jr. dies at 72; former paralegal fought Big Tobacco

Over four years, Merrell Williams Jr. came up with a number of effective ways to smuggle documents from work.

A $9-an-hour paralegal at a tobacco company’s law firm in Louisville, Ky., Williams tucked a few memos at a time into a slit he cut in the lining of his overcoat. Sometimes he stashed cigarette marketing plans and medical studies under his shirt, between his skin and an old weight-loss corset. Then there were the days he wore his pants extra baggy, all the better to slide embarrassing correspondence under the waistband.

When he left work each night, he’d rip open a bag of potato chips. He figured the noise would muffle any rustling from the secret documents he carried — thousands of pages, in all, that eventually helped 46 states secure a historic $206-billion settlement in their lawsuits against Big Tobacco.

“You can call me Robin Hood ... you can call me a prostitute,” he told The Times in 1996. “But I met my goal. The documents got out.”

Williams, who blamed his 1993 quintuple bypass on the effects of chain-smoking Kools and the stress of working for tobacco company lawyers, died Nov. 18 at a hospital in Ocean Springs, Miss. He was 72.

The cause was a heart attack, said his daughter, Jennifer Smith.

Documents unearthed by Williams undercut the tobacco industry’s longstanding denial that it was marketing an addictive product.

In 1994, tobacco executives repeated their standard position in widely publicized testimony before a congressional committee: Nicotine hooks nobody, they said. Smoking is a choice.

Weeks later, amid a cascade of incriminating documents released by Williams, one was particularly glaring. It was a 1963 internal memo from Addison Yeaman, then vice president and general counsel for Brown & Williamson.

“Moreover, nicotine is addictive,” he wrote. “We are, then, in the business of selling nicotine, an addictive drug effective in the release of stress mechanisms.”

Such blatant revelations “helped beat the industry, expose its lies and, most importantly, has resulted in dramatic declines in smoking among adults and especially children,” former Mississippi attorney general Mike Moore said in an email.

An architect of the landmark 1998 settlement, Moore was the first attorney general to sue tobacco companies for the cost of providing medical care to residents with smoking-related illnesses.

Some of the documents appeared to acknowledge a link between cigarettes and cancer, alluding to the disease only with the code word “zephyr.”

Other documents sketched out plans for youth marketing — an activity that officials had long denied.

In interviews, Williams readily admitted snatching the papers and sometimes called himself a thief. But he bristled when tobacco spokesmen made the accusation. It’s like “telling the judge that somebody stole your dope,” he said in a 1997 interview with the Dallas Morning News.

Born in Monroe, La., on Jan. 26, 1941, Williams was raised in west Texas, where his parents had moved to relieve his severe asthma.

Studying drama at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, he started smoking when he appeared in a play as a chain-smoking advertising executive. After trying his hand at acting in New York, he studied at the University of Denver, where in 1971 he received a doctorate in theater.

Williams taught speech and drama, mostly at colleges in the South, but it was an unsatisfying path for both Williams and his employers. By the early 1980s, though, the father of two young daughters was tending bar on Mississippi’s Gulf Coast. He and his wife, Mollie, moved to Louisville, where their marriage broke up.

Nearly penniless, Williams sold cars, cut roses and did odd jobs. But he also had a few paralegal classes under his belt and in 1988 signed on at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs, one of the region’s largest law firms.

The firm, which represented Brown & Williamson, made Williams a “document analyst” — a low-level employee who pored through boxes of company records, earmarking sensitive documents for review. Like other cigarette companies, Brown & Williamson was battling lawsuits from cancer patients.

His bosses didn’t know it, but their new employee, who never had engaged in any kind of social protest, was becoming increasingly outraged.

For a year or so, he let the purloined documents pile up at home. But in 1990, he took a walk in the icy woods of eastern Kentucky and realized he had a moral – even a spiritual – obligation to tell the world about his stash.

“The word ‘God’ comes to mind,” he told the Wall St. Journal in 1999. “It was just an overwhelming moment. … I just had to do something about this one thing.”

Laid off from his job in 1992, he cleared out his desk, shook his supervisor’s hand and stole one last stack of documents.

Williams’ efforts to interest an investigative reporter, an anti-tobacco group and a federal prosecutor fell short. A Louisville attorney approached Brown & Williamson on his behalf and demanded a $2.5-million settlement. The company got an injunction that kept Williams from talking about the documents even to his attorney.

“I’m the only man in the United States who wasn’t allowed to tell my own lawyer my side of the story,” Williams said years later. “Jeffrey Dahmer can kill and eat people — and he could talk to his lawyer.”

Ultimately, Williams hooked up with Richard “Dickie” Scruggs, a well-known Mississippi attorney who had made a fortune in asbestos litigation.

He and Moore, the Mississippi attorney general, carted the documents to Scruggs’ Learjet, flew them to Washington and gave them to Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Los Angeles), head of the subcommittee that had recently grilled the tobacco executives. Soon they were in newspapers throughout the U.S. and posted on the Internet.

Scruggs was later criticized for buying Williams an Ocean Springs house and a 30-foot sailboat, in addition to giving him $3,000 a month for more than a year.

In a deposition, a Brown & Williamson attorney hammered away at the arrangement, finally asking Williams: “Can you tell me why someone would pay you — why, to your understanding — you were paid $3,000 a month to do nothing?”

Williams was quick in his retort: “Because I’m a good-looking sonofabitch! How about that?”

Williams was never prosecuted. Brown & Williamson dropped lawsuits against him and Scruggs, and the two agreed not to pursue their claims against the company. In a complicated transaction, Williams came away with a $1.5-million settlement paid by Scruggs, the Wall Street Journal reported.

In the years since, Williams lived quietly in the Virgin Islands, Florida and Mississippi.

In a 2010 interview with the St. Petersburg Times, he expressed pessimism about effecting permanent change.

“I don’t really care,” he said. “I can’t do anything about it.”

Others believe he already had done a great deal.

“When you explain it to a 5-year-old, what he did sounds so beautiful: ‘He told people that some bad people are poisoning children,’” said his daughter Jennifer Smith, a mother of two. “We’re very proud of the impact he had.”

In addition to Smith, Williams is survived by his wife, Christina Daltro; another daughter, Sarah Ridpath; and five grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.