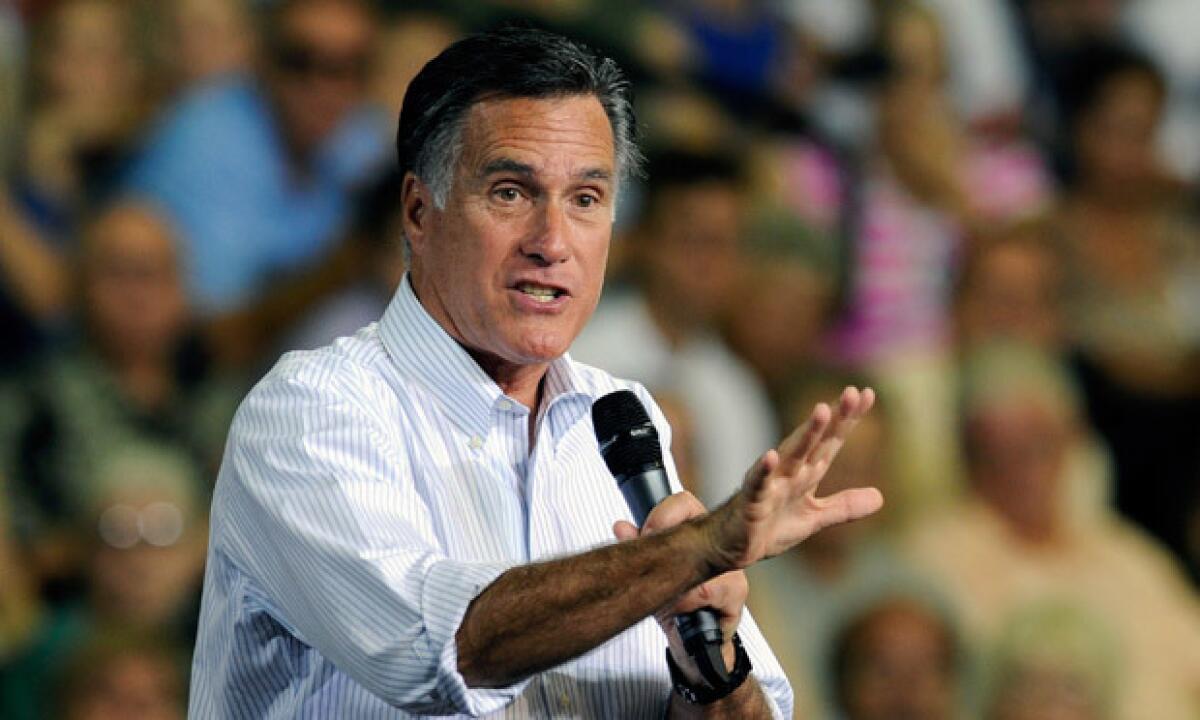

Romney’s edge in outside money a mixed blessing

WASHINGTON — In the escalating money race for the White House, Mitt Romney was supposed to have an advantage: a cavalry of outside groups that could collect unlimited sums and flood the airwaves with advertisements on his behalf.

“Super PACs” such as the pro-Romney Restore Our Future and nonprofit groups like Crossroads GPS lambasted President Obama on air as early as last winter and will probably continue until election day.

FOR THE RECORD:

Campaign money: An article in Section A on Sept. 22 misstated the amount of money that Priorities USA Action, a “super PAC” supporting President Obama, has raised. As of Aug. 31, it had brought in $35 million, not $31 million. —

But their help has been a mixed blessing for the GOP nominee. The ascendance of outside groups, which are legally prohibited from coordinating with Romney and the party, has created a cacophony of political messaging — a dynamic that may be undermining the candidate’s ability to define himself and win over voters.

INTERACTIVE: See the ads, track the spending

“His campaign has to guess at what it thinks other people are going to say and where they are going to say it, and then has to deploy its resources where it thinks there will be gaps, and that’s a hard guessing game to play,” said Brad Todd, a top Republican ad maker.

The resulting message to voters may not be “in sync,” he added. “There’s no question that when you can’t control every nickel spent on your behalf, that diminishes your ability to communicate what you want to communicate.”

Between end of April, when Romney effectively secured the Republican nomination, through Sept. 8, the two sides appeared evenly matched in the advertising war.

The GOP challenger, the Republican Party and their outside allies aired about 303,000 ads on broadcast and national cable television. The Obama campaign, the Democratic Party and anti-Romney groups aired 315,000 ads, according to data from Kantar Media/CMAG, an ad tracking firm, analyzed by the Wesleyan Media Project.

The big difference between the two campaigns is who paid for and produced the ads.

Outside groups were responsible for 54% of the anti-Obama and pro-Romney commercials, according to the Wesleyan analysis. The Obama campaign, however, paid directly for 90% of the ads backing the president’s reelection or attacking Romney.

One reason for the difference is Romney’s heavy reliance on large donors.

Barred by law from contributing more than $5,000 to his campaign, deep-pocketed supporters have sought to bolster his candidacy by pouring money into Republican Party committees and into outside groups. The result: millions of dollars arrayed on his behalf, but not in his direct control.

Obama’s more centralized strategy was partly born of necessity.

Democratic donors have been reluctant to embrace the outside groups that proliferated after a string of federal court decisions in 2010, including the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Citizens United case.

Though Priorities USA Action, the super PAC supporting Obama, had its best fundraising month in August, it has raised $31 million for the election cycle. That compares with $56 million by American Crossroads and $96 million by Restore Our Future, which support Romney.

The Democratic Party has spent no money on independent ads. The Republican National Committee spent $11 million last month alone on ads independent of the Romney campaign.

That has left the bulk of the air war to the Obama campaign itself. And that may give the president an advantage.

Political advertising experts say the campaign benefits when it directs as much messaging as possible to assure what’s being aired on television jibes with the overall strategy.

Too many other ads “diminish effectiveness,” said Steve Lombardo, a veteran Republican strategist who worked on Romney’s 2008 presidential run. When ad buys are made outside the campaign, “there can’t be the same level of discipline when it comes to overarching strategy,” he added.

In recent weeks, for example, ads by Americans for Prosperity hit Obama on failing to fix the economy, while the Republican Jewish Coalition attacked his policies on Israel and Crossroads GPS asserted that middle-class taxes would go up because of Obama’s healthcare overhaul.

There’s another disadvantage to leaning too heavily on outside groups: After Labor Day, their dollar doesn’t go as far.

Under federal law, TV stations must offer candidates the lowest available rate for airtime, a deal not available to political parties and outside groups. As available TV time shrinks in key states and prices rise, a campaign dollar thus goes further than a dollar from an independent group.

Super PACs have proved themselves adept at negative advertising. But they are less helpful when it comes to advocating for Romney’s candidacy. Because outside groups cannot coordinate, the candidate cannot speak directly for himself in ads run by his allies.

“That leaves outside groups little choice but to run ads that contrast the opponent,” said Todd, the GOP ad maker, who is not affiliated with the Romney campaign. “But the case against Obama’s presidency has been made and accepted. The thing that Romney needs to do is make the case for Romney. The best person to do that is Mitt Romney.”

For some groups, making a case for Romney is not necessarily a priority. Americans for Prosperity, a nonprofit group backed by billionaire businessmen Charles and David Koch, has been one of the top independent spenders opposing Obama.

In August alone, they spent at least $18 million on media. But Levi Russell, a spokesman for the group, said the ads were dictated by the group’s policy priorities, not what they think may be most helpful to Romney.

“We’re not here to be a flag-waver for the Republicans,” Russell said. “We’re here to stand up for free-market ideals.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.