Ft. Hood shooting victim is ready for his day in court

LILLINGTON, N.C. — Alonzo Lunsford is blind in his left eye. Half his intestines have been surgically removed. He has trouble walking. He has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

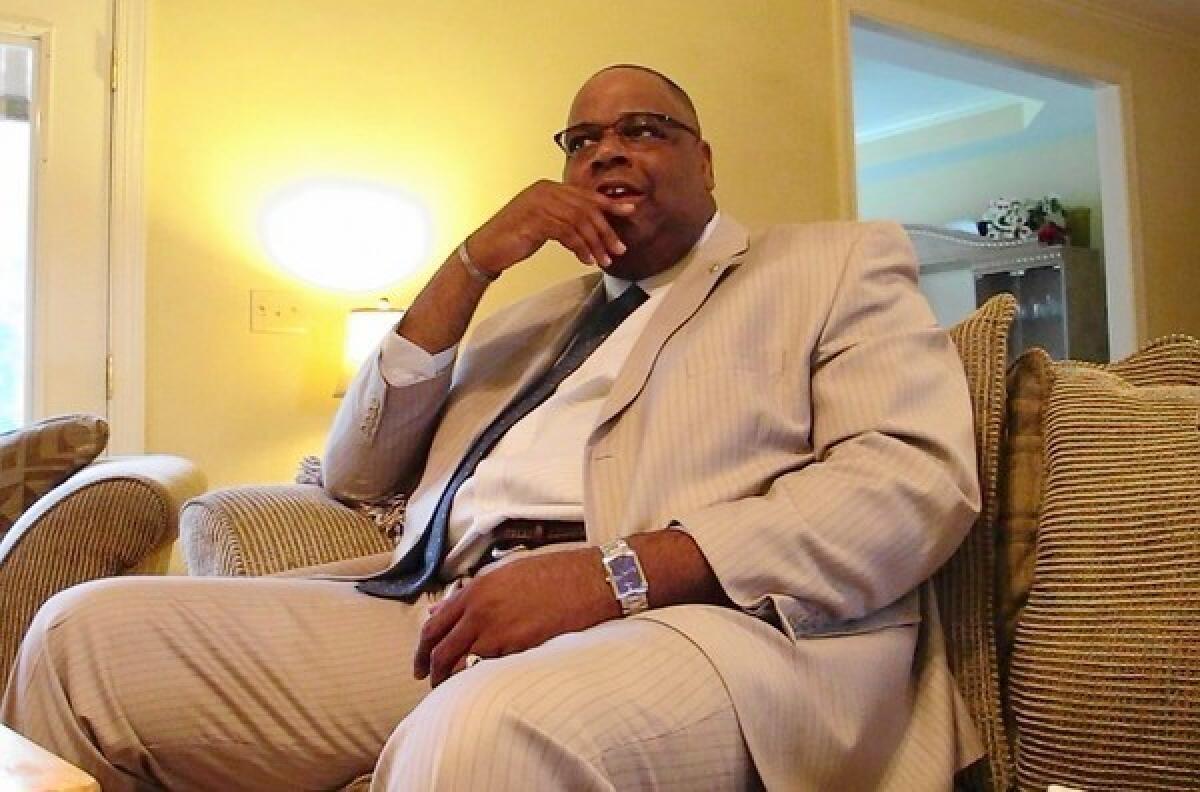

A powerfully built man who stands 6-foot-9, Lunsford was shot seven times at Ft. Hood in Texas in November 2009 in the worst mass shooting on an American military base. Now he’s steeling himself for the day when he will come face-to-face in military court with the man accused of shooting him, Army Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan.

Lunsford, 46, stared down Hasan in a dramatic confrontation inside a Ft. Hood courtroom in 2010. He was the first shooting victim to testify at a preliminary hearing for Hasan, an Army psychiatrist charged with 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted premeditated murder.

Now, with opening statements in Hasan’s court-martial set to begin Tuesday, Lunsford faces the even more formidable prospect of responding to his purported attacker directly: Hasan, who is acting as his own attorney, could elect to cross-examine his alleged victim himself.

Hasan faces the death penalty or life in prison if convicted. He has said he was justified in killing U.S. soldiers about to deploy to Afghanistan in order to prevent the imminent deaths of Taliban fighters, but the judge has forbidden him to use that defense in court.

“I have a lot of anger,” Lunsford said, smoking a cigarette and sipping an energy drink inside his four-bedroom home in rural North Carolina, donated to him by a veterans support group. “It was seven times this man tried to kill me. I took that personally.”

Lunsford is convinced Hasan will try to bait him, hoping he’ll lose his temper and thus undermine his testimony. Because Hasan is a psychiatrist familiar with PTSD, Lunsford said, he knows that people with the disorder have difficulty controlling their emotions.

“He knows how to push those buttons,” Lunsford said. “He would like to try to get me to physically assault him.... The toughest part is trying to control my anger.”

At the preliminary hearing, Lunsford made a point of staring into Hasan’s eyes from the witness stand. Hasan, 42, who is paralyzed from the chest down and in a wheelchair after being shot by police that day, stared back from a few feet away.

“I wanted him to show some type of remorse or sorrow,” Lunsford said. “And I was telling him, male to male, ‘I’m not afraid of you or anyone like you.’”

He said he saw no remorse — only what he called arrogance from Hasan.

The day of the shooting, Lunsford was in charge of the Ft. Hood center in which soldiers preparing for combat deployments were being processed. He testified in 2010 that Hasan shouted “God is great” in Arabic and reached under his uniform for a gun. Lunsford, then a sergeant, crouched behind a counter but was spotted by the gunman.

He described locking eyes with Hasan as a red targeting laser flashed across his face. He closed his eyes, he said, and was shot in the face. He collapsed to the floor, blood pooling under his body.

“I decided I wasn’t going to die like that, defenseless on the floor,” he said. “I’m too big and strong to go out like that.”

He got up and struggled to reach an exit as more shots rang out. It was only later, Lunsford said, that he realized he had been shot several more times. Hassan seemed calm and focused, he said: “He wasn’t crazy — he was on a mission.”

Outside the building, Lunsford was treated by other soldiers as the shootings continued. He remembered singing “Amazing Grace” to keep himself from going into shock, and laughing — he’s very ticklish, he said — when his boots were removed to check for wounds.

Lunsford, a married father of five, has undergone six surgeries, including facial reconstruction where a bullet cost him his left eye. He originally thought he had been shot five times, he said, but doctors later found two more wounds. One bullet remains lodged in his back, and he saved another slug removed from his back last year. A 22-year Army veteran, he retired this year because of his injuries.

Hasan has been permitted to wear a beard in defiance of military regulations and has been dressed in an Army uniform in court despite his objections to wearing a symbol of an American military he has called “an enemy of Islam.”

Lunsford said he intended to wear his Army dress uniform when he testified. “I earned the right to wear that uniform,” he said. “I wear it proudly. I want to show him [Hasan] who’s the better man.”

Since the shooting, Lunsford has volunteered to work with wounded veterans (he coaches an Army wheelchair basketball team). He has spoken to veterans’ groups and victims’ rights groups.

In November, he joined more than 130 other victims and family members in a lawsuit against the U.S. government. The suit, which seeks damages for deaths and injuries, contends that the military and FBI knew Hasan was a radical Muslim who supported jihad against the United States but did not take action.

The FBI has acknowledged that it knew about email exchanges between Hasan and Anwar Awlaki, an Al Qaeda operative in Yemen who was killed last fall in a U.S. drone attack. An independent investigation found that the FBI and Pentagon failed to take action against Hasan even after co-workers described him as a “ticking time bomb” with terrorist sympathies.

The lawsuit also seeks to have the shootings designated as a terrorist attack. The Pentagon has classified the incident as “workplace violence,” leaving victims ineligible for certain benefits afforded to soldiers wounded or killed in combat. Lunsford and other victims are ineligible for Purple Hearts, for instance, because the Pentagon says they were not wounded in combat.

“Building 42003 was a combat zone on Nov. 5, 2009,” Lunsford said, referring to the medical processing center where the shootings occurred.

As part of his PTSD therapy, Lunsford returned to the building on the anniversary of the shootings last year. He stood on the spot outside where he lay bleeding from his wounds.

“Part of me did die that day,” he said. “That Alonzo died, but I was also reborn.”

He knows he’ll have to recount every searing detail in court. He welcomes the opportunity, he said, and he has a message for Hasan.

“I’m telling him, ‘You failed in your mission,’” Lunsford said. “I took his best blows and I’m still here, alive and kicking.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.