Story of the scarf still waits to be told

The Iraqi woman with bone-thin hands and a beauty mark on her right cheek holds secrets in her scarf.

It is yellow and stained with blood, and it made the journey with Nour Khal from a dark road in Basra to an airy bedroom in Manhattan. Now it is hidden in this East Village apartment that she shares with the widow.

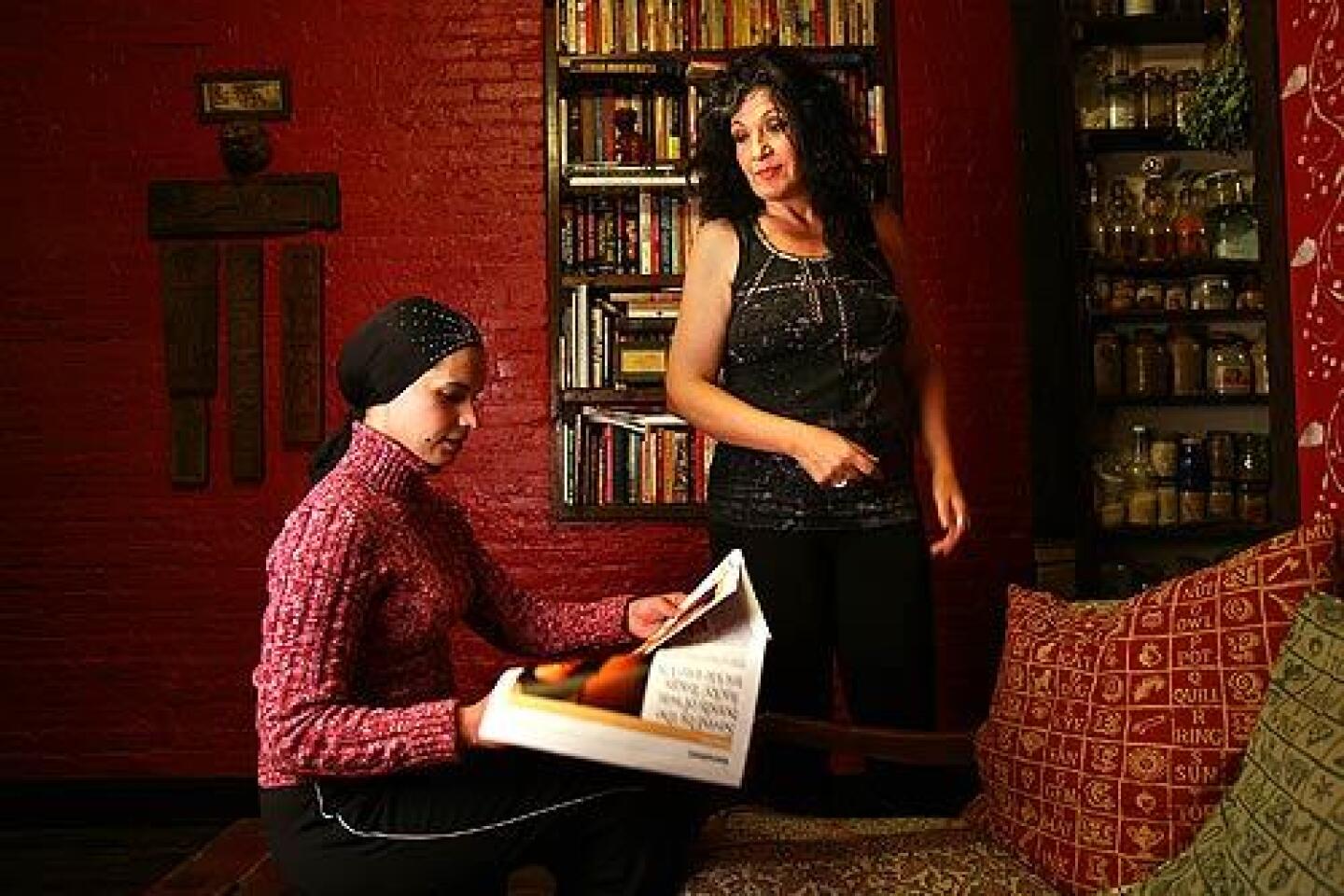

The widow with sad, dark eyes and wisps of gray in her thick black hair doesn’t want to know the secrets of the scarf. Lisa Ramaci looked at it once, touched it, and cried until the sun rose.

It is evening, and the rice pot is popping, the tea kettle steaming.

Khal helps herself to a bowl of saffron rice, taking big bites.

“Is it good?” Ramaci asks.

Khal nods. “I wouldn’t exchange it for a man.”

They laugh.

But they know that is not true. There is one man both would give anything to have with them again. His name was Steven Vincent, an American journalist. He is the man whose blood the scarf holds. Khal, 33, was his translator in Iraq. Ramaci, 51, was his wife.

He is why they are here now, sharing. He is why they find themselves on many nights in the kitchen, talking of dating, or family, or Iraq, until their talk suddenly turns to tears. Why did this happen? Why us? Why him?

The women feel indebted to each other, and so Ramaci takes Khal to doctor’s appointments, teaches her about American culture, lets her borrow clothes, lets her live rent-free, and Khal cleans the place, brings Ramaci water when she coughs, leaves on weekends to give her space, promises she will move out when she finds a job.

Khal feels she owes Ramaci more.

When she arrived in New York six months ago, she was prepared to tell Ramaci everything about that day. But Ramaci could not listen and left the room whenever the topic came up.

Khal let it go, telling herself she would wait for the day Ramaci was ready.

But her flashbacks come strong and often, even in the coziness of this borrowed apartment overlooking 11th Street. She cannot shake the smell of gunpowder, the taste of her blood, the sound of his scream.

On the day the death car came, Khal left her family’s home in southern Basra, Iraq, wearing a long jeans skirt and long-sleeved shirt, her head and neck cloaked in the yellow scarf.

Carrying a purse and black leather briefcase, she made her way to meet Vincent. All afternoon, she felt uneasy. They had been receiving threats for weeks. Once on the street, Khal heard a man’s voice behind her: Why do you work for an American journalist asking critical questions? She turned around, and he was gone. Mysterious people called her cellphone asking the same.Khal had watched Basra, Iraq’s second largest city about 350 miles from Baghdad, transform in two years from a lively city of open-air cafes, fashion boutiques, hair salons and bars into a neglected, fearful place overrun by religious radicals, where anyone could be kidnapped or killed for any reason. Khal and Vincent had decided it was too dangerous and planned to leave Iraq in 10 days.

It was Aug. 2, 2005, just after 6 p.m. Dusk began to blanket the city, but the temperature still felt like 100 degrees. On their way to an interview, Khal and Vincent walked along Dinar Street, a main thoroughfare thriving with fruit markets, a currency exchange and computer centers. They passed people hurrying to shop or run errands before nightfall.

A white car sat parked across the street. Both recognized it. Vincent had mentioned a similar vehicle in an op-ed piece he wrote, published in the New York Times three days earlier, about Shiite militias infiltrating the Basra police force and how the British military had done little to stop them. He quoted an Iraqi police lieutenant describing the “death car,” and he wrote: “A white Toyota Mark II that glides through the city streets, carrying off-duty police officers in the pay of extremist religious groups to their next assignment.”

Four men in police uniforms jumped out. They surrounded Khal and Vincent, pointing guns at their faces. Passersby shouted at them to stop.

“We are police!” the men yelled, shifting their guns to the bystanders. “We know what to do!”

“What do you want from us?” Vincent asked, as Khal translated.

The men ordered them into the car.

Khal knew the danger they risked by surrendering. Vincent tried to pull away from a gunman’s grip. Khal wrestled with another. She broke free, running to hide in an electrician’s shop on the other side of the two-lane street. A gunman followed. He threatened to kill the shop owner if she did not come outside.

She gave in, but continued struggling in the street. Near the car, she saw Vincent fighting, pleading. One man struck him in the head with his gun. They shoved Vincent into the left side of the back seat. When he resisted, one bit his leg.

Khal clutched her briefcase, containing notes from Vincent’s interviews, money and her passport. When the gunmen looked away, she dropped it in the street.

They forced Khal into the car. Sitting on Vincent’s right, she lifted her hand to his head to try stopping his blood. It dripped onto her scarf. A gunman slapped her hand away. She tried again. He punched her in the mouth. Khal spit blood from the gash on her lip onto the seat and floor. Maybe someone would notice the blood or find the briefcase and investigate, she thought. Maybe someone would save them.

Eight hours later, in an apartment in Manhattan’s East Village filled with books, antiques and a built-in stage for literary readings, Ramaci walked in her door and pressed the button on her answering machine. Vincent had left a message at 9:45 a.m., which was 5:45 p.m. in Basra.

He had left for Iraq three months ago, his third trip. Ramaci usually e-mailed him nightly, so he would wake up to her words. But she had spent the day and previous night helping her mother move.

“Are you OK?” Vincent asked in the message.

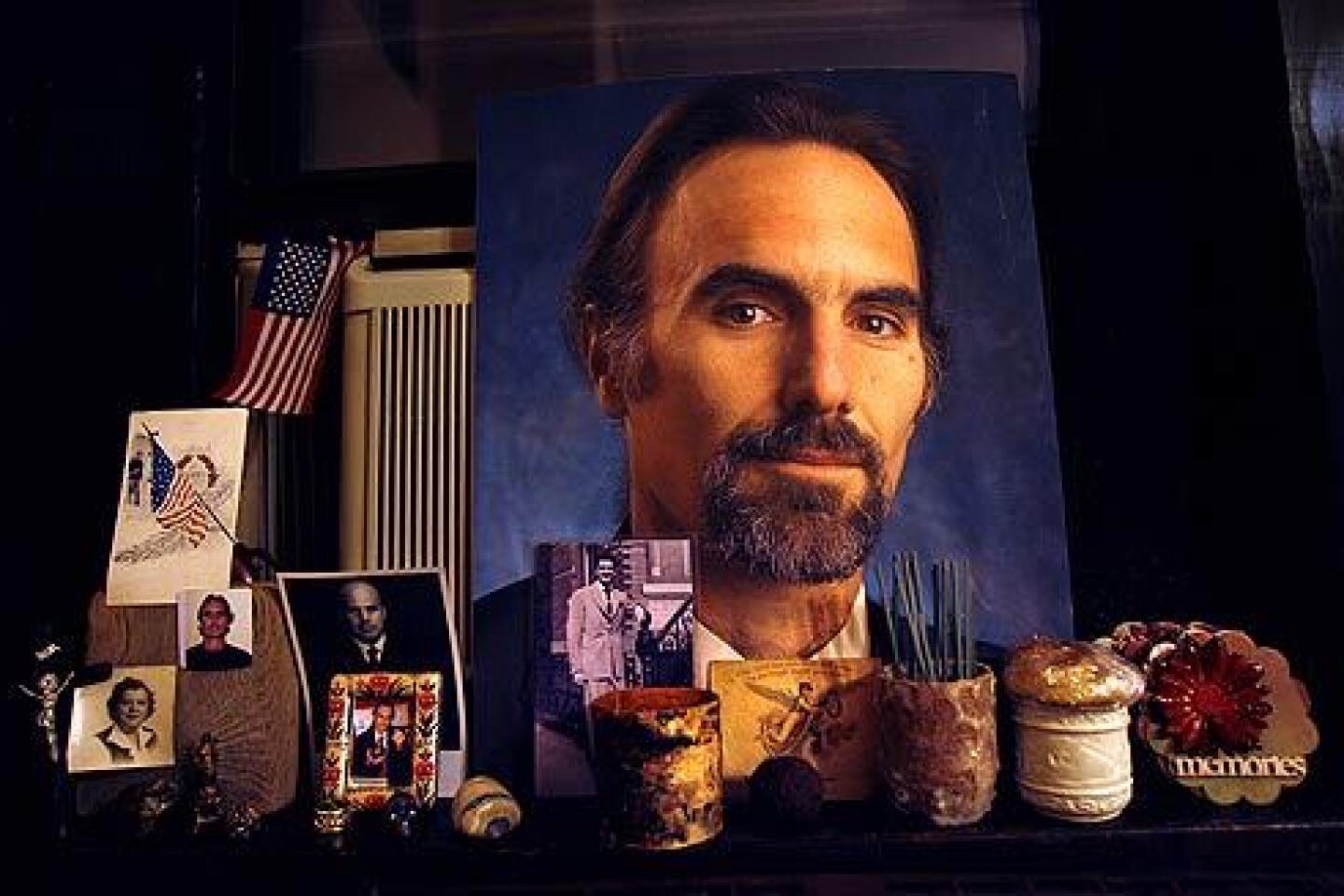

Four years earlier, from the rooftop of their walk-up apartment building, Vincent watched a second plane hit the World Trade Center, and looked on in horror as both towers burned and crumbled. The Sept. 11 attacks drove Vincent, an arts writer, to learn more about the Islamic world. He went to Iraq in 2003, reporting on his travels and encounters for his book, “In the Red Zone,” published in 2004. He had returned to write another.

Ramaci had reason to worry, but tried not to. Days earlier, Vincent had called her in a panic, saying he was afraid he had endangered his translator’s life. He could not leave Khal behind. Ramaci told him to do whatever it took to get her out of the country. If it came down to it, she said, “marry her.”

Listening to Vincent’s conversation that day, Khal took the phone. “Please, thank you so much,” she recalled telling Ramaci, “but I don’t want to keep your husband.”

Ramaci told her: “Just don’t die.”

It was past midnight in Basra and Ramaci figured Vincent would be asleep. She sat down at her computer to answer him, and noticed an e-mail from his editor marked “urgent.”

Ramaci left the editor a phone message. Ten minutes later, he called back and told her a Western journalist and his translator had been kidnapped in Basra. The translator had dropped her ID in the street. It was Khal.

The kidnappers blindfolded Khal with her yellow scarf.

They drove for about an hour, as Vincent told Khal to explain to them that he loved Islam and he loved the people of Iraq. She translated, and told them Iraqis loved Vincent too. Stop translating, they told her. “Shut up!”

The car stopped and different men got in. Khal felt the car moving again. It seemed like another hour passed. The car came to a halt and everyone got out. The men ordered them to take off their shoes before entering a house.

Once inside, they put the hostages in a room and took Khal’s purse. She managed to lift the scarf partly off her eyes. The room had concrete floors, with bedding on the ground. She faced one corner, and Vincent, blindfolded with a red bandanna, faced another.

The kidnappers took a computer memory stick from Khal’s purse and asked about her job. When she begged them to let her call her mother, they taped her mouth.

Khal knew the men might kill them because of their work. She had learned long ago how much risk came with writing opinion and truth. When Khal was 17, she went to prison under Saddam Hussein’s regime for writing a poem protesting the Kuwaiti invasion. She spent 11 months in jail, where she was brutalized.

When she got out, she spent time with an Iraqi poet who gave her strength to continue writing. They planned to marry, but before they could, thieves broke into his home and stabbed him to death, stealing his collection of unpublished poetry.

She spent the next five years reading, working and questioning the world. After the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, she felt reinvigorated. Hussein would be toppled and Iraq, she believed, would advance. She started reading about democracy, dreaming about it. She met Vincent in 2003. His dogged reporting style -- wandering the streets talking to religious leaders, store owners, women, government leaders, police and the military -- made her want to work for him full time.

Khal’s enthusiasm for her country quickly turned to distress as she noticed Iraqi Shiites, who had fled to Iran or were expelled under Hussein, returning in droves to southern Basra, where they began enforcing their strict ideologies. Religious radicals harassed women who did not wear the full chador, and stores specializing in fashion, hair or DVD sales were shuttered. Reports of corruption and assassinations were widespread.

Vincent wanted to write about the rise of Shiite fundamentalism in Basra, and Khal wanted to be a part of it. Soon most people recognized the trim 49-year-old freelance journalist with a gray-speckled mustache and beard, who wore plaid button-down shirts with the sleeves rolled up, accompanied by his slender 5-foot-tall Iraqi translator. She wore lipstick, eye shadow and fashionable scarves, and refused to wear the chador.

The kidnappers interrogated them for six hours. It was dark outside when the men loaded them back into the car. On the drive, Khal heard the men say something to Vincent that relieved her: “From now on, you should know what to write about.” The men would not say such a thing, Khal thought, if they intended to kill him.

When the car stopped, not far from where they had been snatched, the kidnappers opened the doors. The men told them: “Go.”

They rushed outside. Khal told Vincent she would get a taxi and they could go to her family’s home. Barefoot, she started to run. It was past midnight and robbers or other kidnappers could be lurking. Seconds later, she heard blasts and felt her legs buckle. She heard Vincent’s shout echo: “No!” The kidnappers slammed the car doors and sped off.

Khal had been shot in her right shoulder, right thigh and left calf. She saw blood spilling out of her. She turned her head to look at Vincent, who was about 12 feet away, sprawled on the pavement. She called his name, but he did not move. She wanted to get closer to him, see his face, talk to him. She tried to pull herself across the road with her left arm.

If she was going to die, she wanted to be next to Vincent, so people would find their bodies together.

At 11:36 p.m. in New York, Ramaci’s cellphone rang. She recognized the number -- it was the U.S. Embassy in Iraq. The voice on the phone told her the bad news. Officials had found Vincent’s body. His translator was alive.

Ramaci hung up and called Vincent’s parents to tell them their only son was dead.

Two days later, Ramaci spent her 49th birthday in the apartment she had refurbished and shared with Vincent, trying to figure out how to go on without the man she had loved since she was 26.

The couple met in 1982 in Times Square at a showing of the movie “The Road Warrior.” She was an art history major. He was an aspiring writer. They married on Dec. 19, 1992.

She thought of the many nights they had spent in their study smoking shisha pipes, drinking martinis and listening to Sinatra.

A bouquet of sunflowers that Vincent had sent days earlier for her birthday arrived at her door. The card read: “I’ll see you soon. Love forever, Steven.”

The autopsy report showed one bullet had grazed his leg. The other went through his back, into his lung and spine, coming to a halt inside his heart.

Ramaci held his funeral at the church where they had married. The church held 500 people and it was standing-room only. Ramaci buried her husband with Sinatra CDs, music from “The Road Warrior” and a bottle of his favorite gin -- Bombay Sapphire. Weeks passed.

On Sept. 19, Fakher Haider, a New York Times stringer in Basra, was abducted from his home. A few hours later, his body was found on the outskirts of town, his hands bound, a bullet in his head. Ramaci feared there would be more killings, and she worried about the Iraqi translators who put their lives at risk for foreign news agencies.

She started the Steven Vincent Foundation, a nonprofit, to raise money for the families of translators, guides and other media workers who had been killed.

But something haunted her. Vincent had tried to get Khal out of Iraq. Ramaci decided she would fulfill his last wishes and find Khal to bring her to America.

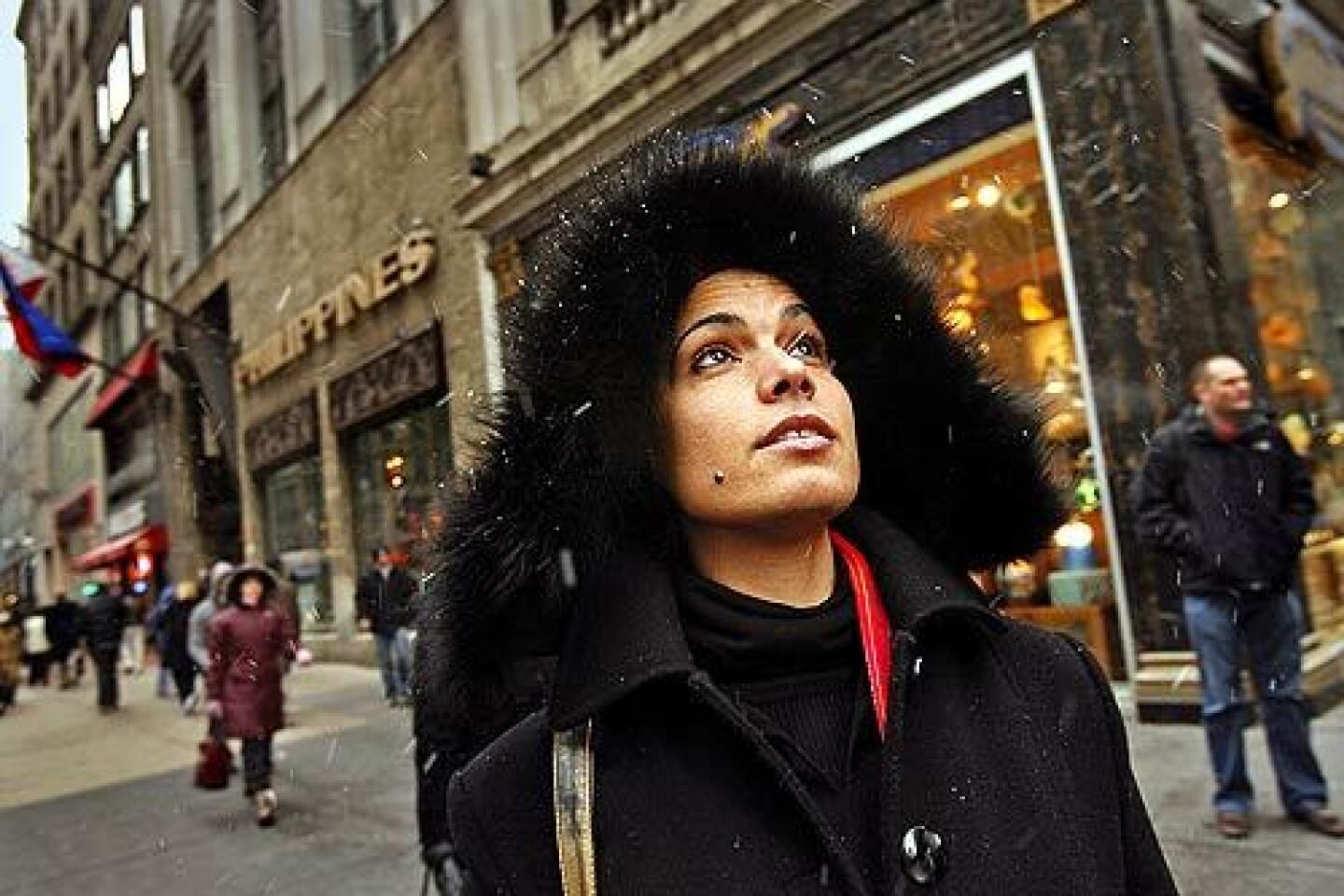

Khal spent three months in hospitals in Basra, Nasiriya and Baghdad, undergoing surgeries and FBI interviews. She didn’t trust anyone. Newspapers reported that she had survived, and there were rumors that religious militants had posted her picture on the Internet asking followers to kill her.

She began to recover and was about to leave the U.S. hospital in Baghdad. The FBI told her to change her name. They gave her $2,000 and returned her purse containing Vincent’s rosary, his hotel room keys and the scarf. They sent her into Baghdad’s Red Zone, an unsecured region where she had no family, no friends and no job.

When Khal was released, Ramaci reached her and said she would try to get her to the U.S. She began sending money to Khal and filing paperwork to get her refugee status.

Khal spent the next year dodging militiamen, while trying to find a job. She fled to Jordan, but spent most of the time in hiding because she was there illegally.

Ramaci was having little success getting officials to allow Khal into the country. She made phone calls and sent e-mails. She pledged to shelter Khal and help her find a job. But no matter what Ramaci tried, she got the same response: Khal did not qualify for refugee status because Iraq was now a democracy, and she had no reason to flee.

Ramaci was losing hope.

In December 2006, Ramaci shared her story about Khal on a radio show focusing on the Iraq refugee crisis. A Human Rights Watch representative was listening and contacted Ramaci, urging her to go to Washington and speak to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

On Jan. 16, Ramaci testified, detailing what she knew about the abduction and her struggle to get Khal to safety: “Please let me help the woman who helped my husband, and who so greatly helped me by being with him in his final moments.”

By June, the paperwork had been cleared and the plane ticket paid for. Khal arrived in New York on June 26.

Ramaci waited outside Kennedy International Airport, wearing a T-shirt that read: “Got Nour.” A cameraman captured the moment on video, as Khal emerged carrying Vincent’s book. She spotted Ramaci and raised her right hand over her mouth, breaking into tears. They embraced. “I’m so sorry I come back without Steven.”

Ramaci rubbed her back and said, “It’s all right. Nour, you’re here, you’re here. You’re safe now.”

Khal sleeps in a twin bed next to a heater in a pale yellow room that used to be Vincent’s office. Against the wall stands a painting of him overlooking the Diyala River, wearing a dark plaid shirt, sleeves rolled up. She feels Vincent everywhere, sees the life he once had with Ramaci, the love they shared.

Ramaci spends long days working as an appraiser at an auction house, coming home late to chat with Khal before they settle in separate corners of the apartment to sleep. When she has time she joins panel discussions about the war. She and Khal continue their work to support media workers’ families and help Iraqi refugees. Both plan to transcribe the notes in Vincent’s computer to finish his book, but so far Ramaci cannot bring herself to comb through his files and read his last thoughts.

There are nights Khal hears the faint sound of Ramaci weeping in the bedroom across the apartment. Ramaci doesn’t hide her grief; it comes in ripples now. It can be a song, she said, the smell of fall, the chill of winter. “I just miss him.”

Khal understands. She thinks of the man she loved in Iraq, who encouraged her poetry and was killed before they could marry. No one was ever punished for his death. The FBI has not found Vincent’s killers either.

In November, Vincent’s parents came to New York and spent a week with the women. Khal offered to tell the story of the day Vincent died. His mother wanted to hear, but his father left the room. So did Ramaci.

A few days later, Khal told Ramaci she had found a job as a receptionist and would move out in the new year. Ramaci asked her to stay longer. She worried about her getting by on her own in New York, and she has grown used to her companionship. But Khal said she did not want to be a burden. Ramaci will be there if she needs help.

When Khal moves out, she will leave the scarf at Ramaci’s apartment, and try to let go of the pain of that day. She will think, instead, of the interviews she and Vincent used to do, the sense of purpose she felt. She will remind herself of the duty she has to keep fighting for what they both believed in, a fight Ramaci has become passionate about too.

“I will give it to her,” Khal says of the scarf, and when Ramaci is ready, she will be there to tell its story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.