Normandy mission

Today, on the 60th anniversary of D-day, world leaders are gathering in Normandy on the north coast of France. Fireworks will light the sky over Arromanches-les-Bains, where the Allies constructed an artificial harbor to support troops infiltrating the countryside from the beachheads. And in little Falaise, a walking tour will be dedicated to the closure of a last pocket of German resistance, marking the end of the Battle of Normandy in late August 1944.

The commemorations will continue for 80 days all around the stretch of coast between Cherbourg and Le Havre where the Allies landed.

FOR THE RECORD: Military designation —A Sunday Travel section article about the beaches of Normandy said Tech Sgt. Frank Peregory, winner of the Medal of Honor, belonged to the 116th Infantry Division. He was a member of the 116th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division.

I went last month, before the fireworks, looking for a little quiet time to think about my father.

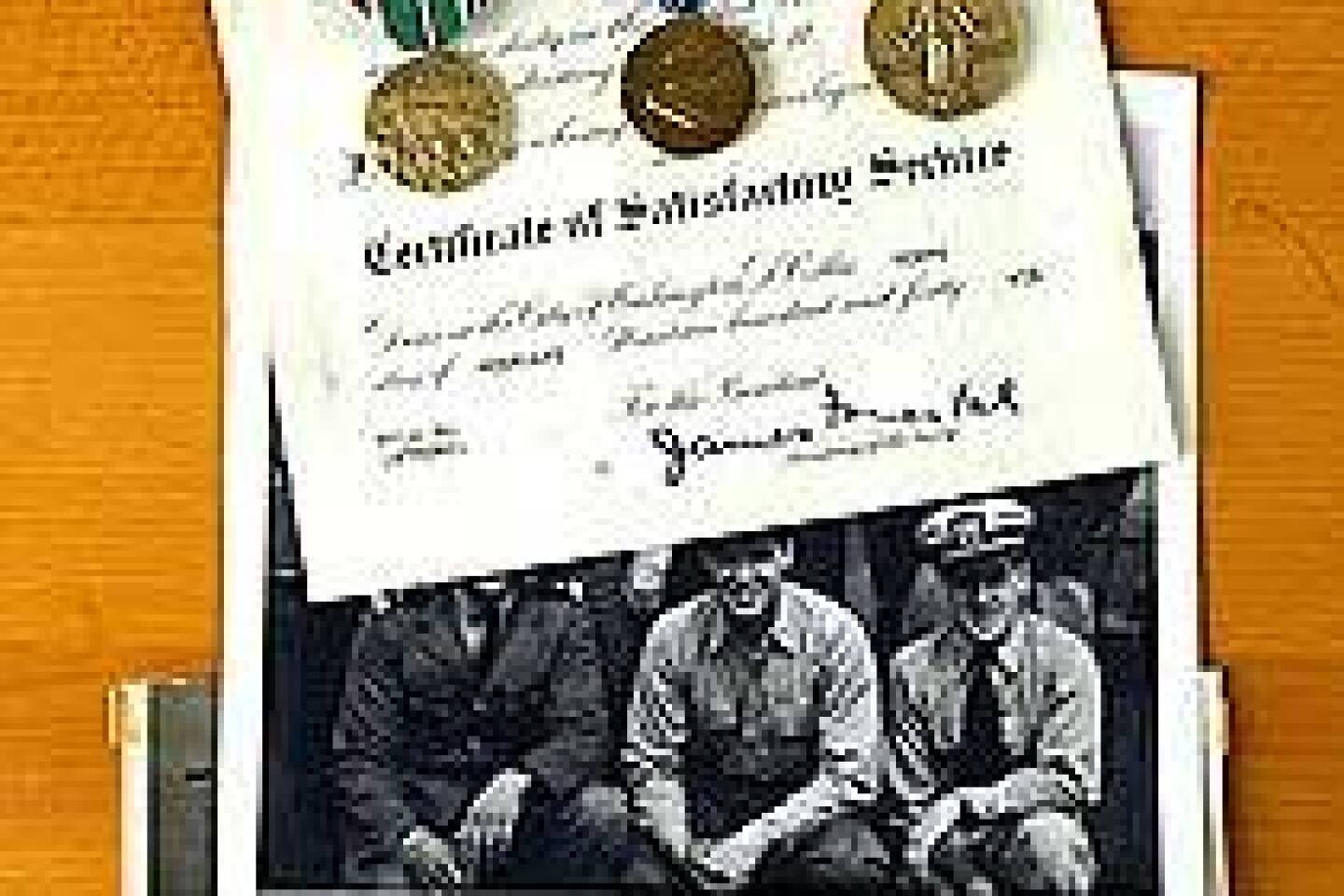

Lt. j.g. John J. Spano Jr. was on a ship that delivered men and equipment to Omaha Beach. Just before 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944, he traded his Navy-issue sheepskin jacket for a Girard-Perregaux watch that belonged to a soldier headed for the landing zone. My father wore that handsome gold timepiece every day. “It is still ticking,” he wrote after he retired. “I hope that young officer came through the war in one piece and is also still ticking.”

Time has run out for many of the American soldiers who survived the war. About 1,100 U.S. World War II veterans die every day.

My own father died two years ago at the age of 82. At the end of his life, his war experiences figured large in his thoughts, especially his participation in D-day, the greatest amphibious attack ever mounted. As a privileged baby boomer, I never completely understood what my father’s war experiences meant to him.

Figuring that out was part of my mission in Normandy, where I walked the beaches, stood at commemorative markers in apple orchards, got lost among hedgerow-bordered Norman lanes where American parachutists landed (and also got lost), and took my bearings from the spires of medieval churches manned by German gunners in 1944.

There are hundreds of World War II sites in the area, from the majestic Normandy American cemetery near Colleville-sur-Mer to endearing mom-and-pop museums with all manner of bric-a-brac from the war haphazardly displayed. In my three days here, I concentrated on sites devoted to America’s big chunk of the D-day action — and those connected to my father.

A history of war

I took the train from Paris northwest to Caen, where I rented a car and quickly saw why the city will never forget the war. It was virtually razed by British bombers in a 65-day effort to drive the Germans out. By the entrance to the train station, there’s a monument to railway workers killed during the war; the main street is Avenue June 6; and the buildings downtown are mostly postwar vintage, except for the castle built by William the Conqueror and the Gothic Church of St. Pierre, surmounted by a 234-foot spire that replaced the one destroyed in shelling during the summer of ’44.A good way to try to fathom it all is to make a first stop at the Caen Memorial, on the northwest side of town. It occupies a pair of modern buildings, one opened in 1988, the other unveiled in 2002, on a cliff with a garden and greensward below. The memorial’s purview goes well beyond World War II. Peace is its point, realized by telling the horrible story of conflict in the 20th century, starting in 1919, at the end of the Great — but not the last — War.

From the main hall, displays (captioned in French, English and German) outline the chain of events that led to another, greater war. A section on “France in the Dark Years” (during the German occupation) follows, with displays on the Vichy government, Gen. Charles de Gaulle’s BBC broadcasts from London that rallied the French and the invaluable espionage efforts of the Free French.

Then it’s on to the war: models of U.S. subs, photos of bombed-out European cities and a 1939 letter from Albert Einstein to President Roosevelt about the possibility of setting off a “chain reaction in a large mass of uranium.”

The story continues in the new building, where visitors are reminded that man’s hostility survived the Second World War. Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War are covered in pictures, film footage and text. Then there’s one last ugly note from the 21st century: a mangled mass of steel beams, donated to the memorial from the World Trade Center.

The last, light-bathed section of the memorial is devoted to peace, from the nonviolence of India’s Gandhi to UNICEF’s efforts to help refugee children. I left thinking that in 10 years a new building will be needed to take us through terrorism and the Iraq war, if we last that long.

Visit to Bayeux

To reach the American D-day landing zones, I took the N13/E46 highway northwest from the memorial. The Norman countryside was so verdant and peaceful, I had to force myself to remember that the very highway I was traveling on roughly marked the Allies’ D-day objective. (They were optimistic, as it turned out; by the end of the day, they had barely advanced beyond the beaches in many sectors.)About 20 miles from Caen, I stopped in Bayeux to see its famed, exquisitely preserved medieval tapestry. Its 276 feet depict, frame by frame in something akin to 11th century comic book fashion, the Norman conquest of England, complete with beguiling Viking ships, ducks, castles and knights in armor embroidered on the borders.

Lunch was a delicious seafood salad at Le Pommier restaurant near the cathedral, followed by a visit to the park where, on June 14, 1944, De Gaulle spoke to the French people for the first time since the German occupation on free French soil. The town’s miraculously intact old stone buildings and winding lanes suggested the weakness of German resistance in the area.

I’d rented a small, utilitarian cottage in Grandcamp-Maisy, a typical Norman village, all gray stone, shuttered windows and lace curtains, scented by the port’s fishy odor. At low tide the beach extends a third of a mile out to sea.

Grandcamp-Maisy has only a handful of hotels, an information office, a little museum devoted to U.S. Rangers who scaled the cliffs at nearby Pointe du Hoc and stone monuments seemingly around every corner.

My favorite was the one on the east side of town, to Tech Sgt. Frank Peregory of the 116th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Infantry Division. He won the Medal of Honor for single-handedly capturing 35 enemy soldiers, armed only with grenades and a bayonet.

The village, about halfway between Omaha and Utah beaches, and thus a fine headquarters for my explorations, is near the oyster beds that line the Cotentin Peninsula to the west. So there were oysters and other seafood at the local restaurants. Seafood is good in its own right but the stuff of the gods when swimming in Norman cream sauce.

One night, over a bowl of small mussels, I remembered that my father, who loved seafood, developed an aggravating allergy to it late in life. I remembered a photo of him just graduated from a 90-day crash course at midshipman school; I recalled that when he first saw his beloved LST (Landing Ship Tank), he thought it ungainly and decrepit, with its keel-less bottom designed for putting men and material on enemy shores; and that, by chance, he met up with his older brother Joe, a motor machinist mate on another vessel, when the 310 docked in North Africa in 1943.

The waiters at restaurants in Grandcamp-Maisy must be used to D-day tourists tearing up over dinner.

Trying to imagine

Above all, I remembered that my father was a part of Operation Overlord, intended to wrest Europe from the Third Reich at a time when the Führer was fighting on three fronts, including Russia.Even capitalizing on Germany’s overextension, tactical information supplied by the Free French and the unprecedented buildup of men and material that followed America’s entrance into the war, Overlord was a gamble. Imagine trying to send 175,000 fighting men, 50,000 vehicles, 5,333 ships and 11,000 airplanes across a 100-mile channel to massively fortified beaches, without alerting the enemy.

For the rest of my stay in Normandy, I tried to imagine it. I spent a day on bloody Omaha, stopping first at Pointe du Hoc, one of the most moving sites in the whole American landing area. There, U.S. Rangers tried to take some of the heat off Omaha’s flanks by climbing 100-foot cliffs to capture big German guns. Lt. Col. James E. Rudder, who led the assault, later said, “Anybody would be a fool to try this. It was crazy then, and it’s crazy now.”

Pointe du Hoc was newly landscaped and bleacher seats had been erected for the anniversary celebrations. Beyond that, the cliffs are eroding now and the pock-marked verge, where more than half of the 225 Rangers who landed at Pointe du Hoc were killed or wounded, looks like an ill-maintained golf course. I stood there, envisioning the Allied armada as it would have appeared to German gunners but could see only sailboats on the horizon.

After that, I stopped at a fortified medieval farmstead in the hamlet of Englesqueville, surrounded by blossoming apple orchards. The proprietor let me taste his cider and Calvados, Normandy’s apple brandy. I bought a bottle of slightly sweet, fizzy cider, the centerpiece of my picnic lunch nearby, atop a German bunker at the west end of Omaha Beach.

I was surprised at the beauty of Omaha Beach — long, wide, flat, a sun lover’s dream. But as far as the Allies were concerned, Omaha was a miscalculation, where German forces far stronger than anticipated awaited American fighting men. “I can still see the beach at Omaha,” my father wrote, “a solid wall of flame and fire, the warships shooting tons of shells at the beach and German fortifications. A terrible, fearsome sight.”

There are three little museums in the Omaha Beach area to tell the story of June 6: one in Vierville-sur-Mer; another in St. Laurent-sur-Mer; and a third, opened this spring, near Colleville-sur-Mer, devoted to the 1st Infantry Division, a.k.a. the Big Red One, which bore the brunt on Omaha Beach. They’re full of vintage Sherman tanks that look as though they never could have budged, mannequins in a full array of World War II uniform, war posters and tins of vintage Griffin ABC Wax Shoe Polish.

One of my last stops of the day was at the Normandy American cemetery, on a bluff above Omaha. I arrived just in time to hear taps and watch the U.S. flag being lowered. Beyond it stretched row upon row of white Latin crosses and the occasional Star of David, set against a velvety-green lawn. In this silent parade ground, 9,386 American servicemen and servicewomen rest, including 39 pairs of brothers, a father and son, and Tech Sgt. Frank Peregory. Someone had left flowers on the grave of Deane L. Quilici, second lieutenant, who was born in Nevada and died July 16, 1944.

The U.S. graveyard is complemented by the German Military Cemetery. It was on my way home, in La Cambe, near Grandcamp-Maisy, at the end of a long avenue of trees. Just after the war, both Americans and Germans were buried there, though the remains of U.S. soldiers were later moved to Colleville-sur-Mer. Its crosses are black, surrounding a mound that contains a mass burial of unidentified victims. Displays describe the difficulty of locating and interring the war dead. No one knows how many Germans still lie far from home in Libya or Russia; 240,000 German soldiers died or were wounded in June 1944, in Normandy alone.

The next day, there was Utah Beach to see, with its seaside Musée du Débarquement and monuments; the handsome church at St. Marie du Mont, whose steeple helped many U.S. paratroopers orient themselves after being dropped in the wrong places; and the town of Ste.-Mère-Eglise, which figured in the classic 1962 WWII film “The Longest Day.” Red Buttons played John Steele, a paratrooper who landed on the church steeple, then hung from a flying buttress for several hours, playing dead, while the town fell to American forces. A billowing white parachute and John Steele’s effigy still hang there.

There was also time for a short cruise aboard the Col. Rudder, a sightseeing ship out of Grandcamp-Maisy harbor. If I was going to find my dad in Normandy, I thought, it would be on a boat, seeing the beaches as he did — from the water.

It was cold, and the sea was rough so we headed for protected waters west of town in the estuary of the River Aure. I huddled in my seat on the top deck, a little disconsolate. I couldn’t feel my father’s presence on the boat or anyplace else in Normandy. Nor could I conceive that he might have died here. Even now I can’t hold the thought in my mind that he is gone.

But after visiting Normandy, I can understand a little better why D-day was one of the critical moments in his life that made him who he was. He had an unerring moral compass and optimism, bred in part from having been part of something utterly great and good, the battle for freedom that started on D-day.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.