China’s man at the anchor desk

Edwin Maher was having a “Broadcast News” moment, feeling a flicker of self-doubt, an attack of the sweats waiting to happen beneath the white-hot studio lights.

The veteran Australian TV reporter and weatherman was starting a new job abroad as a prime-time news anchor. But decades of on-camera presence couldn’t prepare him for this gig, mouthing the party line for an imposing state-run TV network with armed soldiers posted at the entrance gates.

He was reading the news in communist China.

“I stared into the lens and mentioned the Communist Party and I almost lost it,” he recalled. “It was a routine story about some move the regime was making. But I remember thinking to myself, ‘I can’t believe I’m doing this.’ ”

Maher is the first non-Chinese news anchor for state television’s English-language station, CCTV International. He speaks almost no Mandarin, but that’s of little concern to his bosses.

He was hired in 2003 as the station introduced a Western face to shake its image as a stodgy government mouthpiece, famous among foreigners for its wooden presentations and sometimes-tortured English. Maher anchors the news up to four times a day for millions of viewers worldwide, including the U.S. Critics say Maher isn’t a reporter at all, but a shameless government yes-man who gives all Western journalists a bad name. Maher answers bluntly: He says he simply doesn’t care.

Maher made his mark as a sort of Aussie Willard Scott, an eccentric weatherman who ad-libbed his reports by using map pointers such as carrots, scepters and an ice cream cone. Maher has given the weather standing upside-down and once poured a cup of water over his head during an Australian heat wave.

He came to China on a whim after his wife died from a brain tumor in 2001. Since then, he’s become a minor celebrity who has also written a series of articles for government-run China Daily on his fumbling efforts to learn the language and culture. This year, the illustrated columns have been turned into a book, published in English and Chinese.

But his fame lies in his CCTV broadcasts. With a solemn face and precise delivery, the graying Maher (who will say only that he is in his 50s) reports the Chinese version of events on everything from relations with the United States and Taiwan to the nation’s annual crop yields.

If there’s a hole in the story, don’t expect Maher to fill it. He knows, for instance, he can’t utter the phrase “mainland China,” which censors believe suggests acknowledgment of an independent Taiwan.

During a recent broadcast on the impact of the controversial Three Gorges Dam, he reported only the government’s assurances that no environmental damage was being done, with no mention of warnings from the West that the massive project could become an ecological disaster.

“It’s a matter of acceptance,” said one station official, who declined to be identified. “If you like working here, obey the rules. If you don’t like the rules, get out.”

Maher is among three dozen foreigners at CCTV-9, performing roles such as editing and checking grammar. But he is by far the most visible. Fans use his broadcast as an English tutorial. Many monitor what kinds of ties he wears, even the pen he uses. He has received mail from as far away as Van Nuys, from someone who wanted his autograph.

His broadcasts reflect the emerging global media now blurring the lines between politics, language and nationality. CNN, the BBC and other international networks feature foreign reporters and anchors. But the trend is also affecting networks considered fringe players on the TV journalism front.

Al Jazeera has a team of English-speaking reporters from 45 nations, recruited from many of the globe’s major networks. In diversifying its news reports, CCTV officials say they hope their foreign reporters will help provide a more credible Chinese perspective on world affairs.

Media experts call the move a public relations ploy.

“It sounds like an effort to lend a whiff of Western-style credibility to their news operations, in a superficial way, without having to actually adhere to high standards such as fairness, independence, balance, public service and accuracy,” said Neil Henry, a UC Berkeley School of Journalism professor.

“But a propagandist is a propagandist, no matter what one’s race or country of origin.”

Maher hears from his critics -- from irate e-mail writers to the foreigners he meets. “One writer said there was no excuse for what I was doing. And Westerners on the street will ask how I feel about being a mouthpiece for the Chinese government.”

He’s unapologetic. He calls his CCTV anchor job the biggest break of a career that has spanned decades in Australia and his native New Zealand.

“I don’t feel that any of us are employed to be stooges,” he said of fellow foreigners at the station. “But obviously there are limits.”

Maher said he writes his own lead-ins to stories and is consulted on such issues as tone and length. But censors have the last word.

“If the reports aren’t balanced, there’s nothing I can do. I can’t stand up and say, ‘You’re not giving the other side.’ ”

Maher points to media censorship elsewhere in the world, including the U.S., where many media outlets refuse to carry alternative stations such as Al Jazeera. “Nobody wants to touch it,” Maher said.

Orville Schell, a China expert at the Asia Society in New York, agreed that media censorship isn’t limited to the Middle Kingdom.

“In any society, there are very ponderous forms of censorship. They are just more obvious in China,” he said. “Is this a bad thing for Mr. Maher to read the news on Chinese TV? There are many people doing corporate PR. Is that a bad thing?”

But Maher, he said, surrendered any guise of objectivity this year when he accepted the Friendship Award, the highest honor the Chinese government grants to foreign experts.

“China has a long tradition of kept foreigners who are friends of the government through thick and thin,” Schell said. “What he is doing is not journalism as we understand it in the West. I’m not sure I would want an exclusive diet of news from a ‘friend of China.’ ”

Others see Maher as a maverick and entrepreneur.

“He figured out a niche -- it sounds like a good thing for him,” said Joan Bieder, a senior lecturer at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism who specializes in TV reporting, writing and production.

Bieder has run training sessions for TV reporters working for Singapore’s government-run network, another place where, she said, “there was no room for interpretive journalism.”

“Most Americans,” she said of Maher, “would say he’s a sellout.”

Before becoming a voice of China, Maher had no desire to even visit the country. He was too busy riding a successful career as a reporter and announcer.

In the 1980s, on a whim, he accepted a job as weather anchor for the Australian Broadcasting Corp. in Melbourne. He fast developed a following for his easygoing style and zany reports. There was a fan club. He wrote several books, including “Confessions of a TV Weatherman,” and once recorded a meteorologically inspired rap lyric for an Australian band and its song, “Your Weekend’s Gonna Be Ruined, But It’s Not My Fault.”

The fun and games ended in 1999 when Maher’s wife of 33 years, Robyn, was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He abandoned his career and was at her side when she died in 2001.

Maher mourned. He developed a second career as a voice trainer. Then one evening, while fiddling with his shortwave radio at home, he heard voices in tentative English giving the news in China. He wrote the station an e-mail as a joke, offering his services as a pronunciation coach.

The station took him seriously and offered him a job. After consulting with his grown children, Maher made the leap.

He worked for China Radio International for six months before being offered a job for CCTV. The job paid less than half of what he was making in Australia, but he relished the challenge.

At first, he felt enormous pressure, knowing millions were watching the station’s newest effort at legitimacy. Friends said he licked his lips too much on-air.

Maher soon found his rhythm. In addition to his anchor job, he is the station’s voice coach.

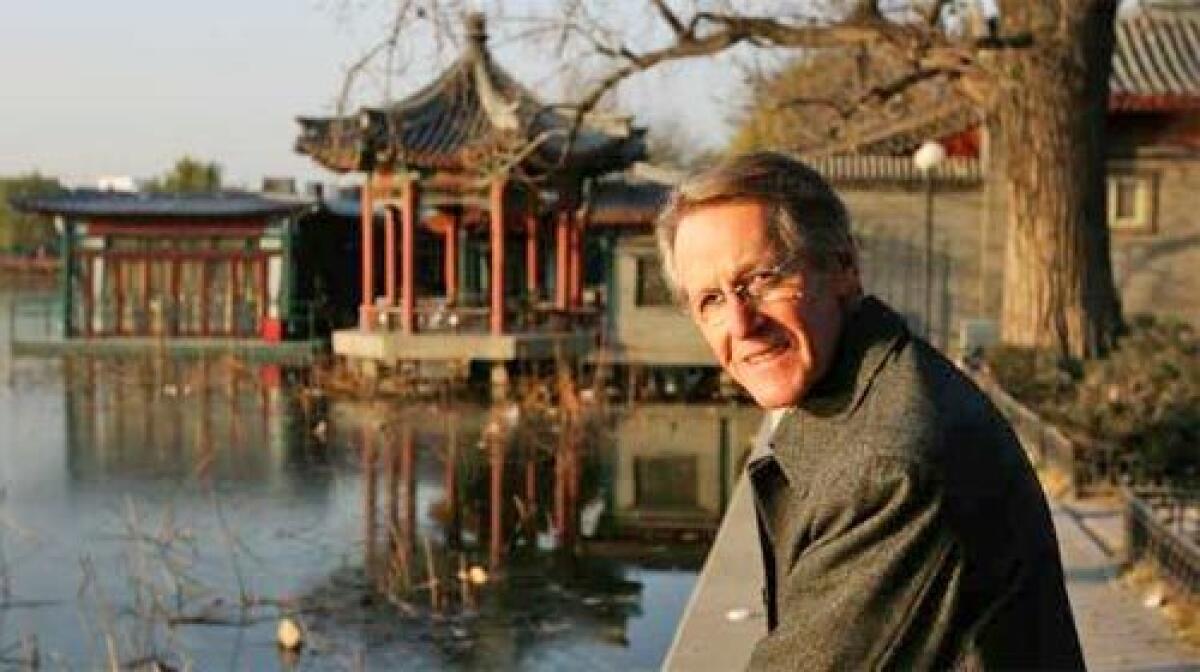

A rail-thin man with oversized glasses who prefers suits over causal clothes, he likes to ride his bicycle around his Beijing neighborhood. He takes buses, not cabs, as a way to meet locals and continue his Chinese-language studies, which he calls “the hardest thing I have ever done in my life.”

Although he feels at home among neighbors, at work cultural walls stand. Maher once addressed a group of Chinese meteorologists, who questioned his lighthearted Australian broadcasts.

“The Chinese take their weather seriously,” he said. “They wanted to know how I could joke about a topic that was likely to kill people.”

Over time, he said, he has seen the station become less rigid: Reporters aren’t as stone-faced, and their English is improving. There has also been a slight move toward balanced news, he said.

After reporting a vote to impeach Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian, Maher wondered whether the station would report the results if Chen, whom many Chinese see as a political thorn advocating Taiwan’s independence,won the decision and stayed in power.

“Fortunately, they did,” he said. “It was a little bit of balance. It’s getting better. The door is opening a little bit wider.”

Maher said he remains amazed at the progress the Chinese have made in 30 years since the repression of the Cultural Revolution. “I’m proud to be a part of that,” he said. “People can see it differently. I don’t care.”

Each day, when he arrives at the sprawling CCTV compound, not far from Tiananmen Square, he passes the armed soldiers.

But Maher has even found a certain peace with that.

“They certainly were imposing at first,” he said. “But they’ve warmed up to me. A few even say hello, so I don’t worry about it.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.