Britain smug about euro crisis but has its own problems

It’s not hard to find some smug smiles in Britain these days as the rest of Europe grapples with a debt crisis that has cast doubt on the future of the euro.

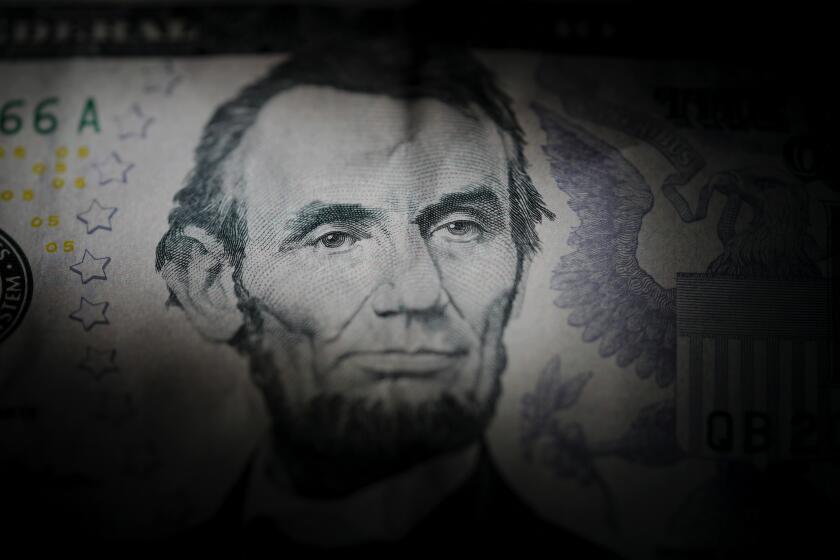

This island nation has fiercely resisted adoption of the single regional currency and has clung to the pound as a symbol of tradition and independence. Before a summit of European Union leaders this week, his usual Scottish dourness barely succeeded in masking Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s schadenfreude when he declared that the euro’s problems were for euro-using nations such as France and Germany to solve, not British taxpayers.

But Britain is in no position to sit back and relax, much less crow, analysts say, not when its own economy is still in such shaky condition, its credit rating in danger of an embarrassing downgrade and its government sinking deeper into debt.

The global downturn has hit Britain particularly hard, in part because of London’s status as an international financial center. Britain’s was the last of the major economies technically to emerge from recession, and that only barely: It grew by a tiny 0.1% in the final quarter of last year, and economists fear it could just as easily start contracting again.

Like many other countries, including the United States, Britain went on a spending spree to stimulate demand during the recession’s darkest days, funding infrastructure projects and cash-for-clunkers-style rebates. And as elsewhere, that has compounded a budget deficit now at a level not seen since World War II.

In fact, as a percentage of gross domestic product, Britain’s yawning deficit is close to that of Greece, whose 12.7% shortfall triggered the euro crisis. Athens’ deficit is more than four times the prescribed limit for countries in the so-called Eurozone and investor panic over a possible default has hammered the euro’s value.

“From Day One, I’ve been absolutely delighted we’re not in the Eurozone, and I hope we never are,” said Peter Bickley, an independent economic consultant. “It has been quite handy that we could blow the deficit out when we needed to.”

But the problem now “is not so much that they’ve blown it out over the last two years, which during the recession was not a bad thing to do,” Bickley said. “The problem was the inherited position after the previous decade of fiscal incontinence. We came into it with the public finances in a really weak state, and they’ve gotten a lot worse.”

Just as Greece has unveiled an austerity plan to get its finances in order, Britain must soon bite the fiscal bullet as well. Exactly what and how deeply to cut is already shaping up as the dominant issue in the national election that must be held by early June.

The opposition finance spokesman, George Osborne of the Conservative Party, caused a minor stir in December when he said that Britain might be on the same path to misery as Greece.

This week, banking giant JP Morgan Chase & Co. added to the debate when it noted in a report that, by a number of measures, Britain’s fiscal situation “looks significantly worse than in the mid-1970s,” when London was forced to seek a humiliating bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

But 2010 is not 1976, the report adds, in alignment with many economists who say that, though Britain is in tough circumstances, a Greece-style crisis does not loom on the horizon.

“The U.K. is much better placed than Greece. British national debt is lower, and productivity growth is stronger,” said Linda Yueh, an economist at Oxford University. “Also, Greece ran into problems because of the inaccuracy of its statistics, whose correction contributed to a loss in confidence. The U.K. certainly is not in that position.”

But Britain does need to present a credible plan soon for taming the deficit, or else risk driving up government borrowing costs, Yueh and other analysts say.

In an ominous move last May, credit agency Standard & Poor’s put Britain’s hitherto strong credit rating on a “negative watch.” Last month, the agency demoted the British banking sector to a lower tier in terms of soundness, based on Britain’s “weak economic environment” and the government rescue of several ailing banks.

“Postelection, if what is produced [as a cost-cutting plan] is not thought to be credible -- and there’s a risk of that -- a rating downgrade is perfectly possible,” said Bickley, the economic consultant.

To calm investors, the ruling Labor Party, which is trailing in the polls, has vowed to slash the deficit in half within four years. The Conservatives have pledged to make more drastic cuts.

As for Greece, Britain may yet be on the hook for bailing it out, despite distaste for the idea.

If the EU as a whole, instead of just the Eurozone, decides to give credit assurances for Athens or to issue EU-wide bonds, then British taxpayers will have no choice but to be involved because Britain remains one of the 27 EU member states.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.