A searing assault on Iraq’s intellectuals

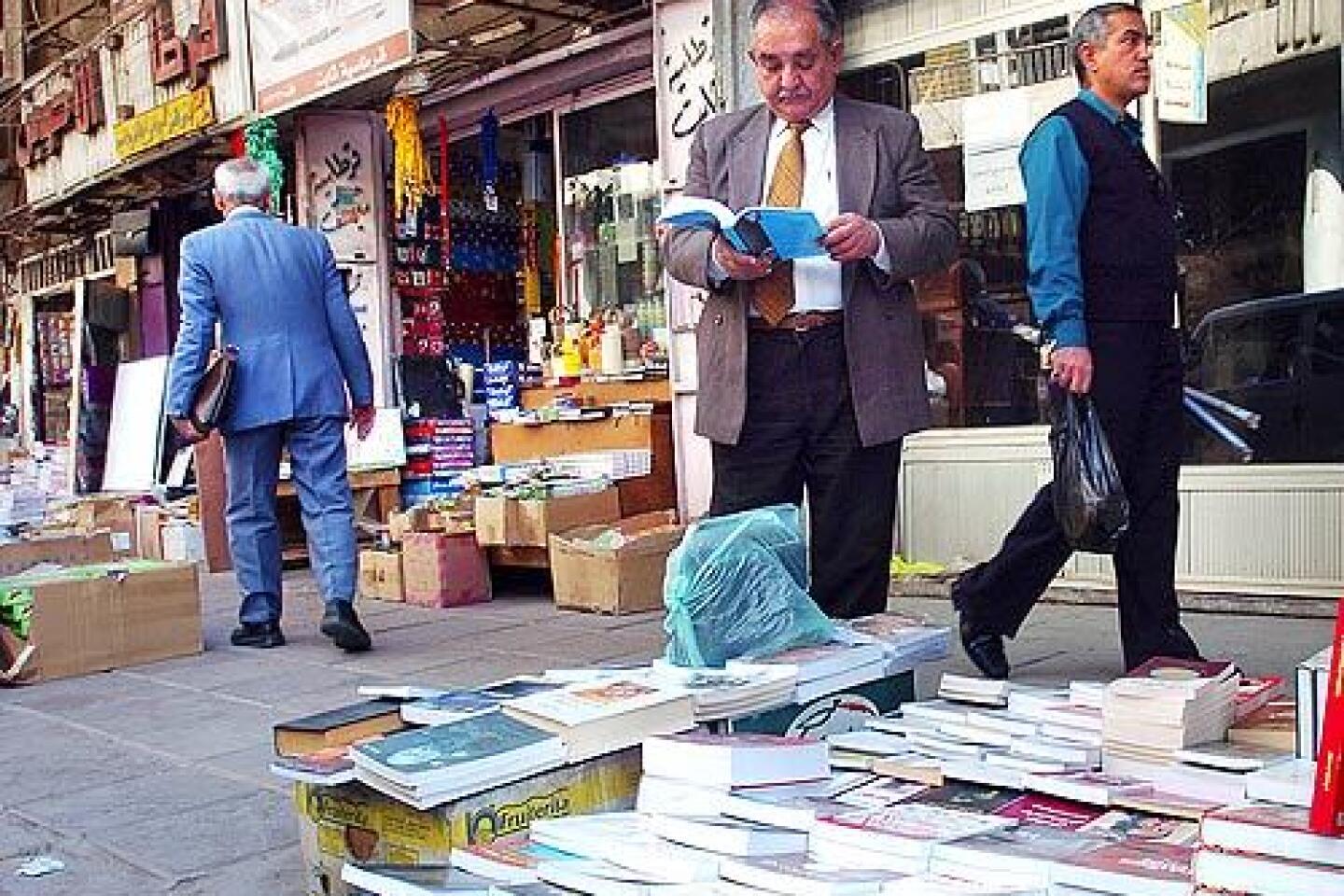

BAGHDAD — Artist Jabbar Muhaybis stood amid the ashes of Baghdad’s storied literary bazaar. Bloodstained pages were scattered at his feet. A wooden crate, eerily reminiscent of a coffin, covered his head.

Muhaybis spread his arms wide and, in a symbolic gesture, sadly intoned from the darkness of his crate: “The light will not shine here again.”

Days after a suicide bomber plowed his explosives-laden truck into the heart of Mutanabi Street, Baghdad’s intellectual icons gathered to mourn a place that had been their inspiration and refuge through decades of invasion, war and dictatorship.

Iraq’s urban, educated, largely secular middle class had everything to gain from the fall of Saddam Hussein’s oppressive and isolating regime. Four years later, it is on the way to being wiped out.

Writers, doctors and university professors are hunted down and killed. Entrepreneurs and engineers are kidnapped for lucrative ransoms. And the symbols of Iraq’s intellectual heritage — its bookstores, libraries, museums and archeological sites — have been plundered and burned.

More than 200 Iraqi academics, 110 physicians and 76 journalists have been killed since Hussein’s fall, according to figures compiled by government ministries and professional associations. Thousands of others have fled the country.

As the U.S.-led occupation enters its fifth year, holdouts of middle-class society are starting to ask: Who will be left to pick up the pieces when the fighting is done?

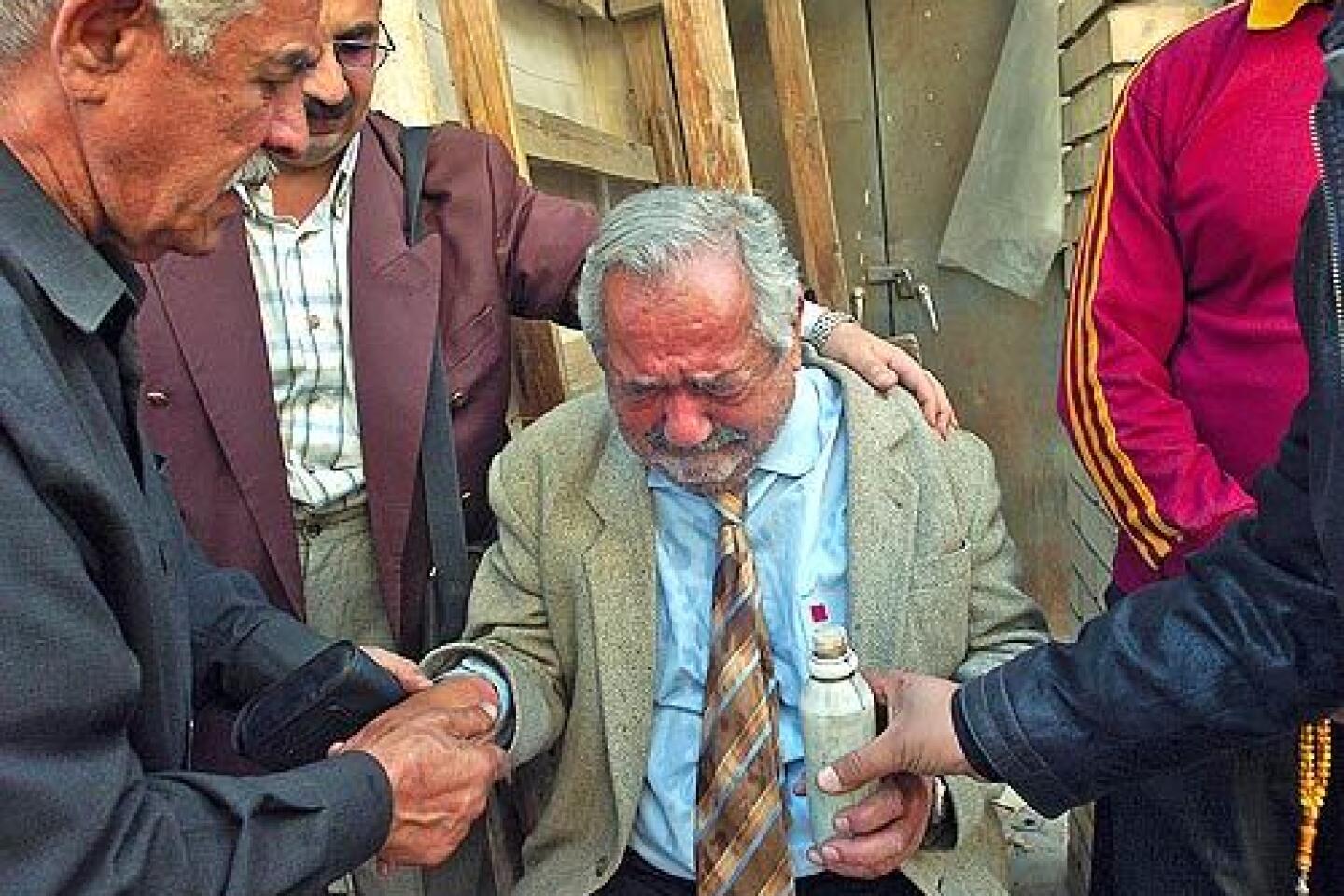

Days after the Mutanabi Street blast, Nejah Hayiani, 61, gingerly pulled a blackened trouser leg from the rubble. A cellphone attached to the waistband told him it belonged to his dead brother, Mohammed.

“We didn’t find bodies, we just found pieces of flesh,” he said bitterly.

A family legacy in ruins

The brothers grew up on Mutanabi Street. Their father opened the Renaissance bookshop in 1957. Here, artists, poets and book lovers from all backgrounds converged to leaf through dusty tomes of Ottoman history, religious texts and Shakespeare’s sonnets, always watchful for the eavesdropping government informers who lurked in the alleys. From there they would wander over to the Shahbandar cafe for a glass of tea in a room swirling with lively debate and the sweet smoke of water pipes.Mohammed Hayiani took over the shop from his father. A nephew, Yehyia, opened a small store nearby, specializing in lawbooks. Now both shops are in ruins, their owners and staff slaughtered in the March 5 blast that killed more than 30 and sent thousands of charred pages fluttering into the sky.

“The future is dark,” Nejah Hayiani said. “If the thinkers are targeted and killed, who will lead Iraq? Only the ignorant.”

Militants seeking to disrupt Iraqi society deliberately target the wealthiest and most senior professionals. But even those of lesser means are frequently caught in the bloodshed.

At the National Library and Archives, director Saad Eskander is trying to rebuild a collection that was burned and looted in the first weeks of the invasion. In a blog on the British Library’s website, he describes the conditions that have turned the work of a librarian into a life-threatening proposition: gunshots through a window, bomb blasts and battles in the streets. In December alone he reported four employees killed, two kidnapped, 58 threatened and 51 displaced.

Iraq once was a modern society, with well-developed infrastructure and health and education systems. All that is in pieces now, and a generation of technical expertise has been ravaged with no prospect of filling the vacuum.

Attendance at Iraq’s schools and universities has plummeted as campuses have become battlegrounds in the war between Shiite Muslim and Sunni Arab Muslim militants. University lecturers are afraid of their own students, some of whom report to militant groups.

“They want a people who can’t think,” said Abu Mohammed, head of Iraq’s Assn. of University Lecturers.

Abu Mohammed’s predecessor, a geology professor, was killed in a drive-by shooting after he campaigned to keep religion and politics off Iraq’s campuses. Fearful for his own life, Abu Mohammed asked to be identified by a traditional alias based on his son’s name.

Many students and lecturers, meanwhile, are translating their resumes into English and applying for posts abroad.

“In a few years, I think you will see the middle class will have disappeared,” Abu Mohammed said. “The guns, the bad people will control everything in our lives.”

Many members of Iraq’s middle class are the product of the 1960s and ‘70s oil boom, when the term “Baghdadi” became shorthand for big spender.

But a United Nations embargo imposed after the 1991 Persian Gulf War, and the U.S.-led purges of members of Hussein’s Baath Party from government institutions after the 2003 invasion, devastated them. Though a flood of U.S. investment helped create a new elite, even it could not escape the swell of violence, first from Sunni Arab insurgents, then from sectarian militias and, finally, from common criminals.

Late last year, gunmen snatched businessman Fakhir Zihairi and held him, blindfolded, for 15 days, while they used his cellphone to negotiate a ransom with his family. The kidnappers’ asking price was $150,000, but they settled for $7,000.

After he was freed, Zihairi immediately applied for a passport to leave Iraq. He sold his house, furniture, printing business and his wife’s gold jewelry in preparation for the move to Cairo. He has no intention of coming back.

“I will leave Iraq to the gangsters, the terrorists, the sectarians and the chaos,” he said.

Flight of the middle class

More and more families are trying to do the same. Outside the passport office on a recent Monday, guards pushed back a crush of about 50 people waving documents and clamoring to get inside.About 2 million Iraqis now live abroad, and as many as 50,000 join them every month, according to U.N. figures. Middle-class families, with the means to buy the tickets and visas, make up a large portion of those who have fled.

Aida Mousawi never thought she would be among them. A Shiite from the southern city of Najaf, she survived years of torment under Hussein’s Sunni regime. Her husband, a biology professor, went to work one day and never returned, swallowed up, she believes, in one of the dictator’s mass graves.

For 14 years, she nurtured the hope that she would find him alive, or at least get his body back. It was only when she attended the opening of one of those graves that she realized she would get neither wish.

“There were maybe 600 people in there piled on top of each other,” she said. “How can you find someone in there?”

For all that time, she had suffered quietly at home, raising four children alone. But the collapse of Hussein’s regime changed that.

“I thought this was our time to emerge,” she said. “I am the Iraqi woman, and this is the day when the Iraqi woman should come forward and demand her say.”

She started a women’s center, which offered English and computer classes, ran a clinic and Internet cafe, and helped teach rural women to vote. But like other such groups, especially ones with ties to the U.S. military, it drew the suspicion of the city’s conservative Shiite leaders.

One morning in December 2005, a white Opel carrying three gunmen pulled up alongside Mousawi’s car as she was driving to work.

“The man sitting in the back seat opened his door, had a good look at me, pulled out a Glock pistol and emptied it into my car,” she said.

Mousawi was hit in the back and arm. Her eldest son, who was also in the car, took two bullets in the chest but survived.

The attack only increased Mousawi’s resolve. She was assigned 10 police bodyguards and went back to work. But when the guards showed her a letter from their commander instructing them to leave her within 24 hours, she knew it was time to go. By then, Shiite militant death squads had infiltrated Iraq’s security forces.

A week later, she was in Syria. Her frustration is palpable through the crackling phone connection.

“If Iraq should have a strong government, where we can have a free voice, then I’d absolutely like to come back and help build the country, brick by brick,” she said. “But not [under] this government of thieves and gangsters.”

zavis@latimes.com

Times staff writers Salar Jaff, Wail Alhafith, Suhail Ahmad, Said Rifai, Saad Khalaf and a special correspondent in Baghdad contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.