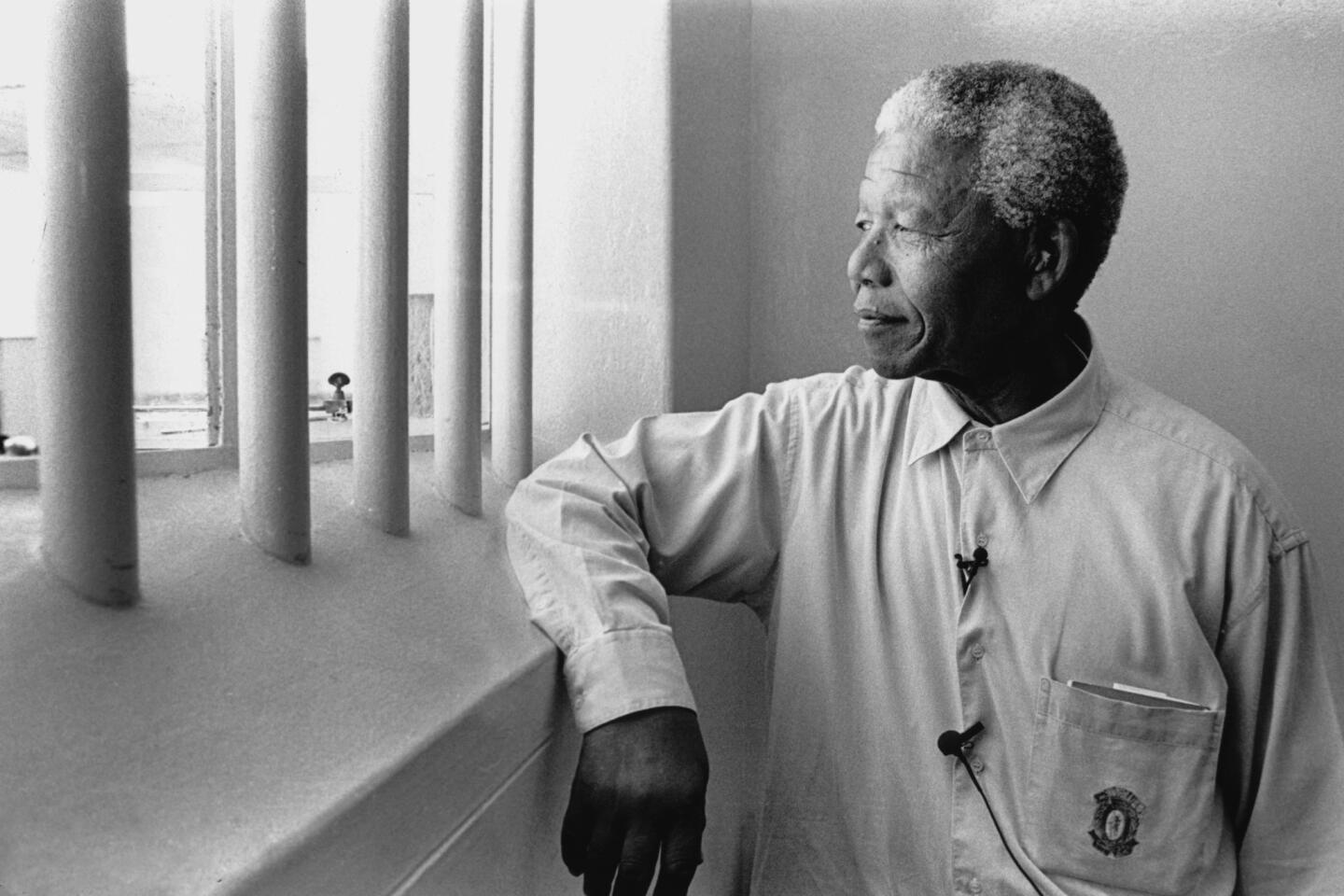

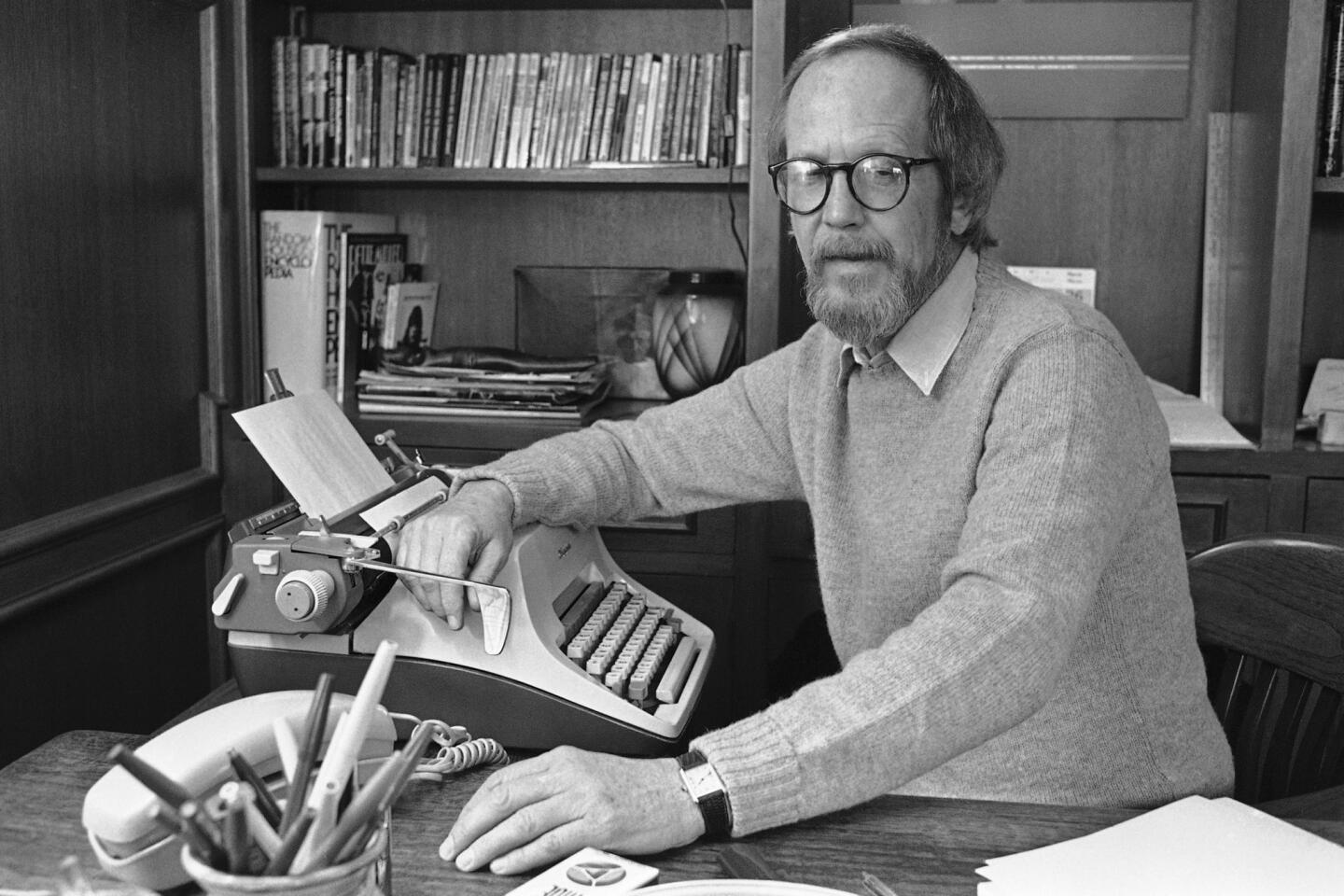

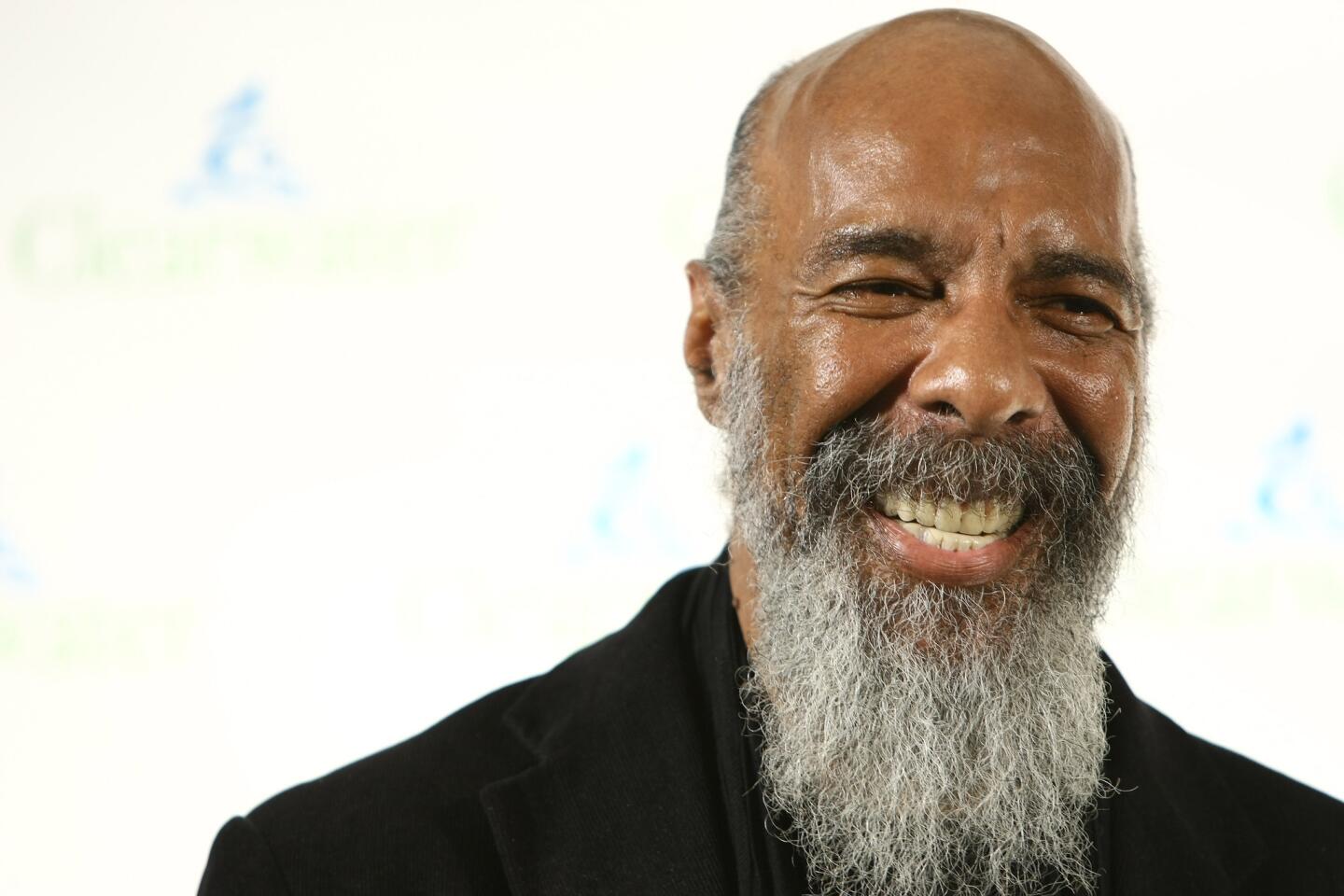

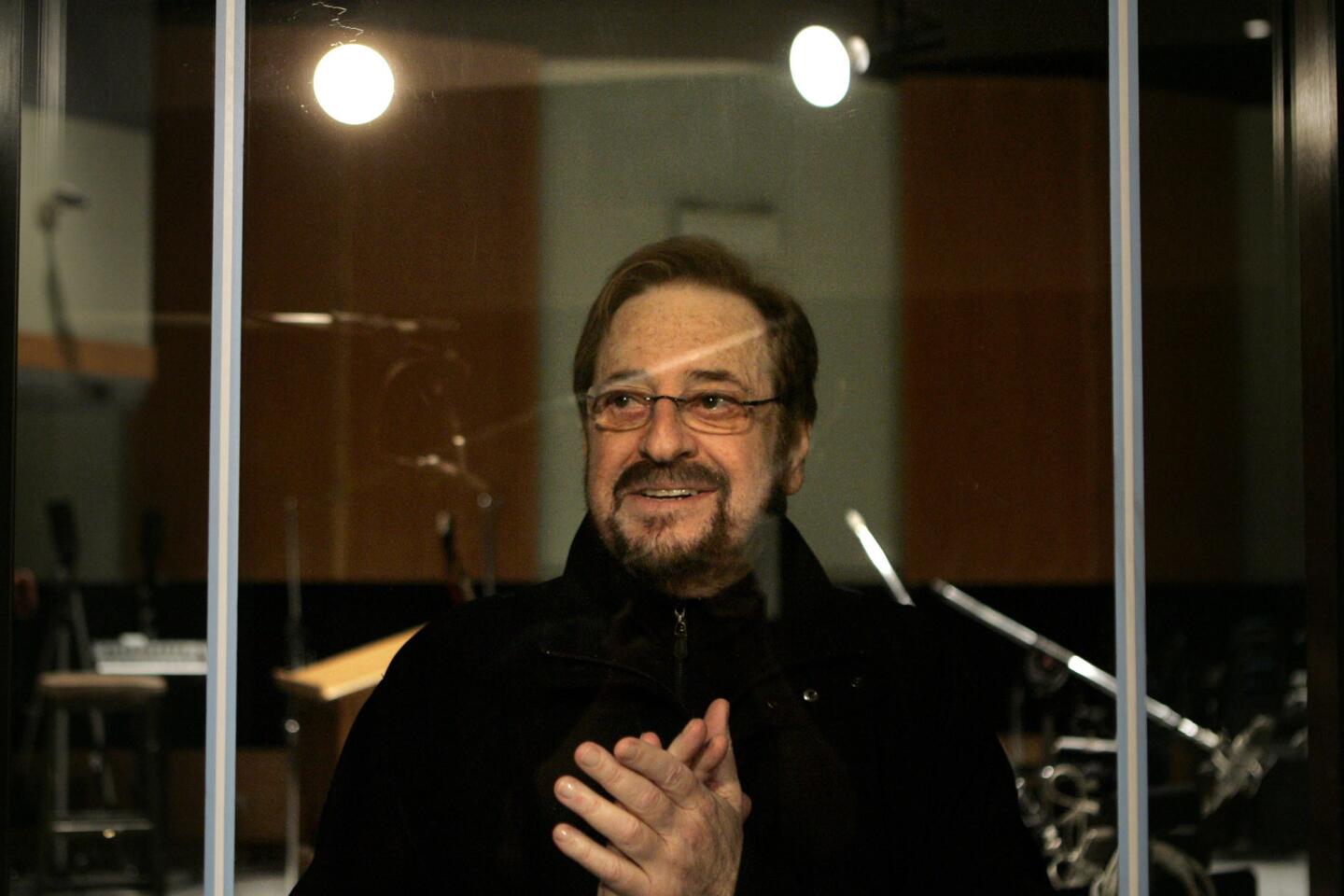

Maurice L. McAlister dies at 87; co-founder of Downey Savings & Loan

Maurice L. McAlister overcame a dirt-poor childhood in Texas to achieve prominence in two fields as a young man — first as a builder, then as the head of Downey Savings & Loan, which became a Southern California banking fixture for decades under his leadership.

Despite his considerable wealth, the man everyone called Mac remained a down-home character, living mainly in Bullhead City, Ariz., where he could hunt quail and elk and fish for bass.

He nurtured close family ties along with the business: One of his three daughters was on Downey’s board and a son-in-law rose to chief executive. So McAlister was doubly stung late in life, family members said, when regulators seized the S&L in 2008 amid the mortgage meltdown and another daughter, Karla Drew, died of cancer in 2011.

McAlister, who had heart disease for decades, died Feb. 13 at a daughter’s home in Corona del Mar, his family said. He was 87.

The S&L, which opened with a single branch in Downey in 1957 and later moved its headquarters to Newport Beach, was known for its well-located offices — a consequence of McAlister’s strategy of developing shopping centers and placing a branch in each one.

Downey had more than 170 offices in California and Arizona when regulators shut it down in 2008 and turned its deposits and assets over to U.S. Bank. It had lost $547 million in the first nine months that year, largely because of risky pay-option mortgages — the adjustable-rate loans that let borrowers pay so little each month that their loan balances rose.

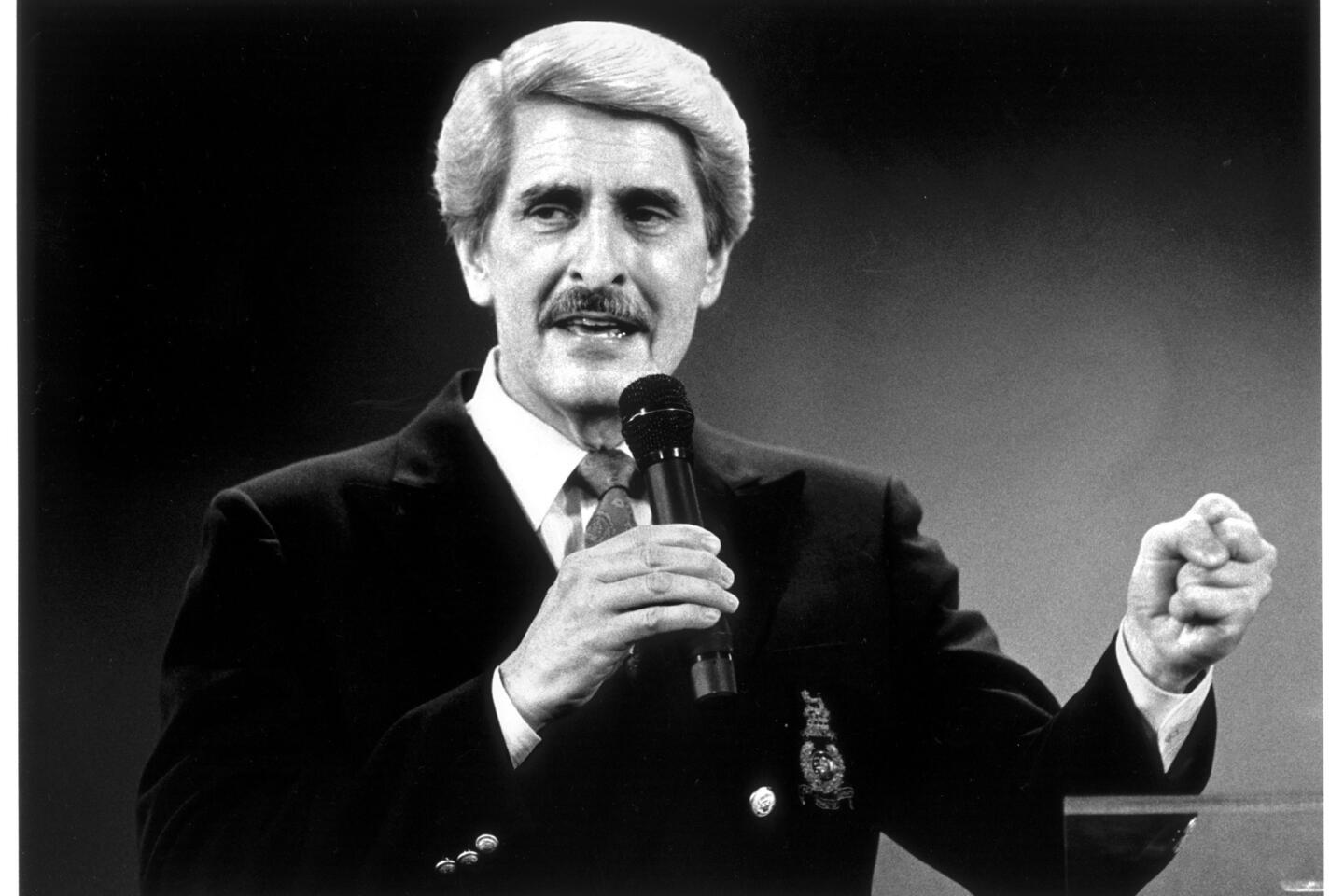

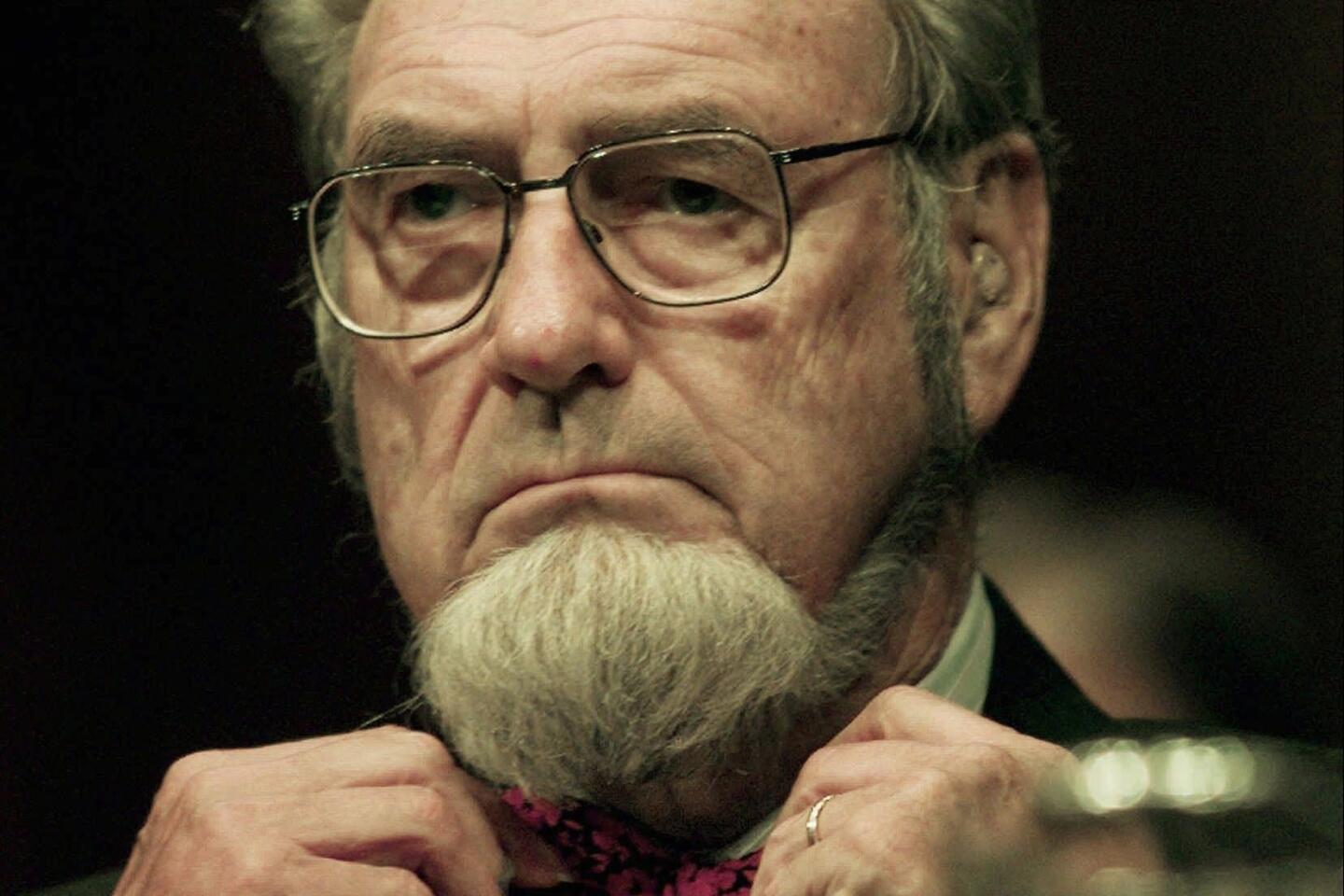

Despite the losses, the plain-spoken McAlister contended that Downey had more than enough capital and solid assets to survive the financial crisis. He said he had protected the thrift by requiring 20% down payments from borrowers, avoiding the 100% financing that was one of the causes of the housing bust.

“There’s basically nothing you can do with those people back there in Washington, D.C.,” he told the Los Angeles Times last fall. “In my opinion, they just targeted California and decided to close all the thrifts.”

Noted for charitable giving, McAlister donated funds each month to churches that provided food and medical care to the needy, and would stand anonymously in food lines, talking with people about their struggles, his family said.

One person he repeatedly helped was Hector Nevarez of Whittier, who purchased and fixed up hundreds of homes in low-income areas with loans from McAlister — housing that banks were slow or unwilling to lend on. Short on cash for one such deal, Nevarez asked McAlister for more financing than usual.

“And he said: ‘Why don’t I just do the whole thing?’ He did 100%, which is very, very rare,” Nevarez said. “He trusted me completely, just like a father.”

Born April 26, 1925, in Booger Hollow, Ark., McAlister moved to Brownsville, Texas, with his family as a young child. He picked cotton alongside his mother and when he was about 12, he went to work for a market that kept cattle out back, said Daniel Rosenthal, the son-in-law who went from appraiser trainee to chief executive at Downey.

“He wasn’t even a teenager and his job was to kill the cattle and gut them,” Rosenthal said.

The family moved to South Gate, where McAlister graduated from South Gate High, enjoying only one class — wood shop, Rosenthal said. His entrepreneurial spirit emerged in a scheme that involved providing free wood to classmates so they could make furniture that he sold on consignment.

As a teenager, he obtained his real-estate license. He soon bought a lot in South Gate, built a house and sold it, which marked the beginning of what became McAlister Construction and later McAlister Homes.

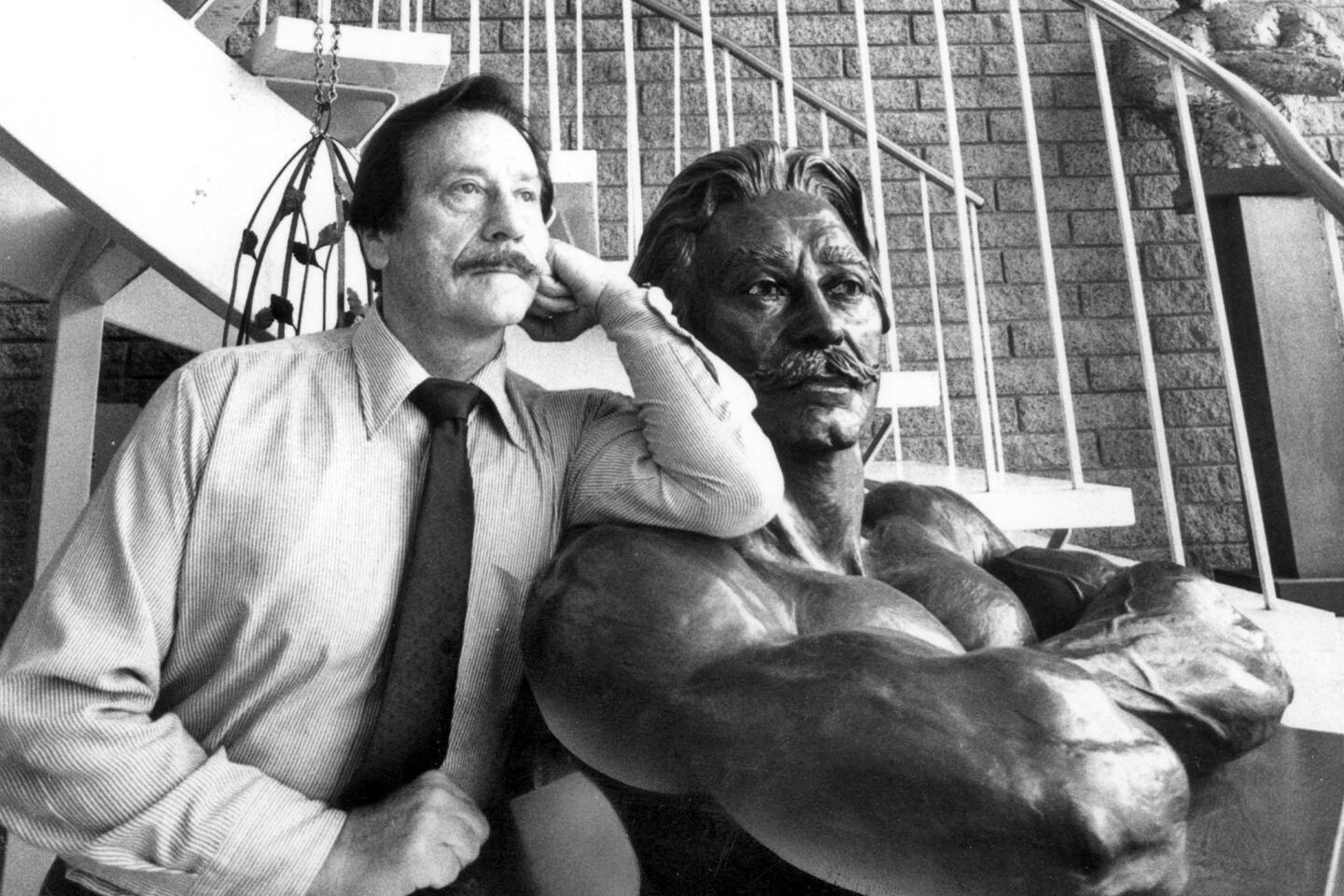

McAlister was barely in his 30s when he started Downey, almost on a whim. When he jokingly complained about the cost of his loans and suggested he might start his own bank, his lender responded: “That might be the best thing you could ever do,” Rosenthal recalled.

Soldiers returning from the Korean War were among the first customers at Downey, which McAlister co-founded with Gerald H. McQuarrie, an appraiser and mortgage banker who died in 1992. The two Macs, as they were known, soon turned their attention to commercial real estate.

Like many savings and loans, Downey made large direct investments in real estate in the 1980s after the Reagan-era deregulation of the industry. Hundreds of thrifts collapsed when real estate soured in the second half of the decade, but Downey emerged in good shape — a testament to McAlister’s judgment then, analysts said, and a contrast to the enormous later losses on pay-option loans.

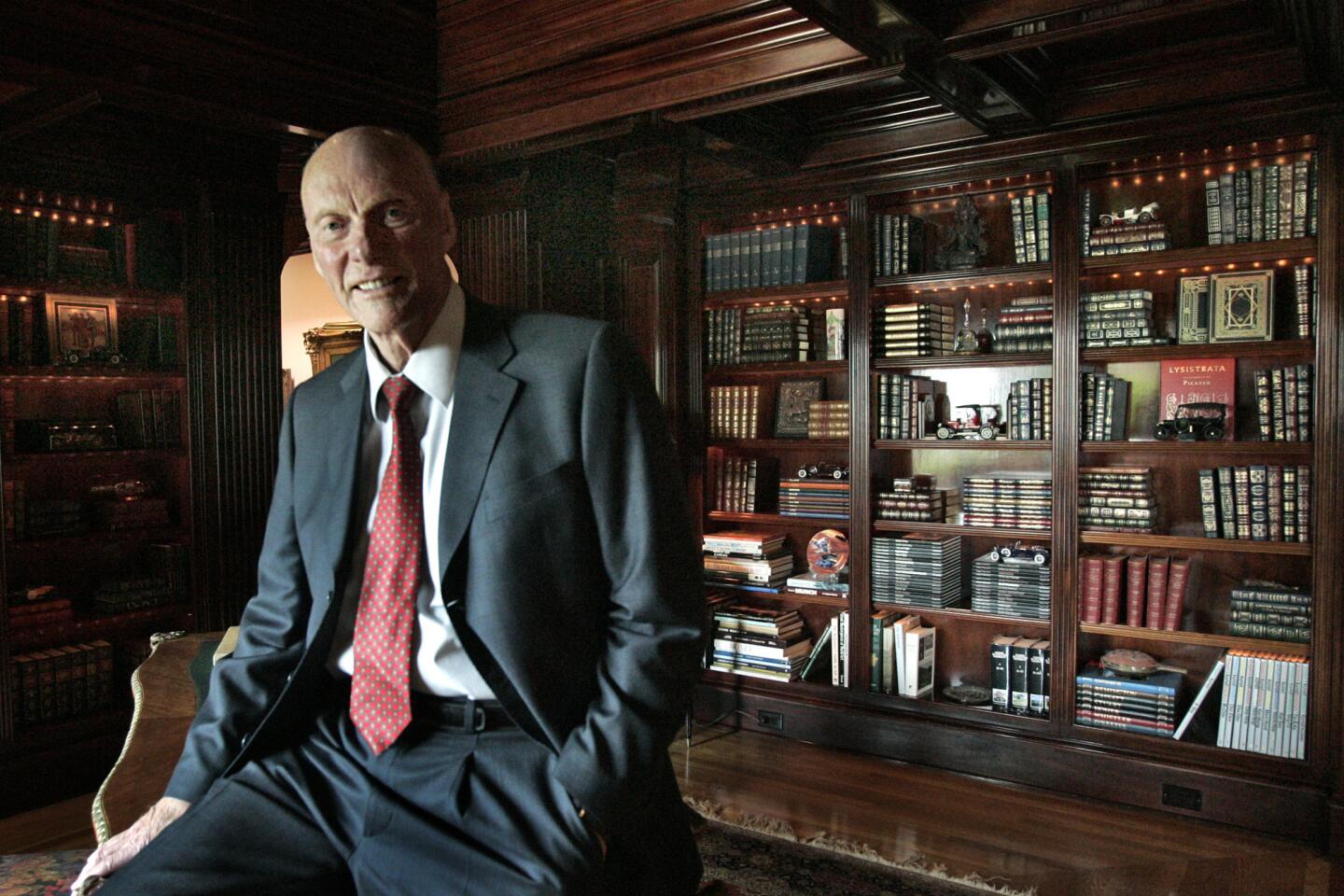

McAlister retired as chief executive in the mid-1990s but remained chairman, hiring and replacing a series of successors, including Rosenthal.

Downey’s downfall wiped out McAlister’s 20% stock in the thrift, once worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which lost $407 million on the failure, threatened to sue him and 10 other insiders for unsafe practices, citing too many pay-option loans and too little documentation of borrower incomes.

FDIC records show the group settled by paying a collective $32 million, mostly covered by corporate insurance but with $1.93 million coming from McAlister’s pocket. He and three others, including Rosenthal, agreed to be banished from the banking industry.

Survivors include his wife of 59 years, Dianne; daughters Cheryl Olson and Laura Daniels; brother Ronald “Tex” McAlister; six grandchildren’ and seven great-grandchildren.

Services are pending.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.