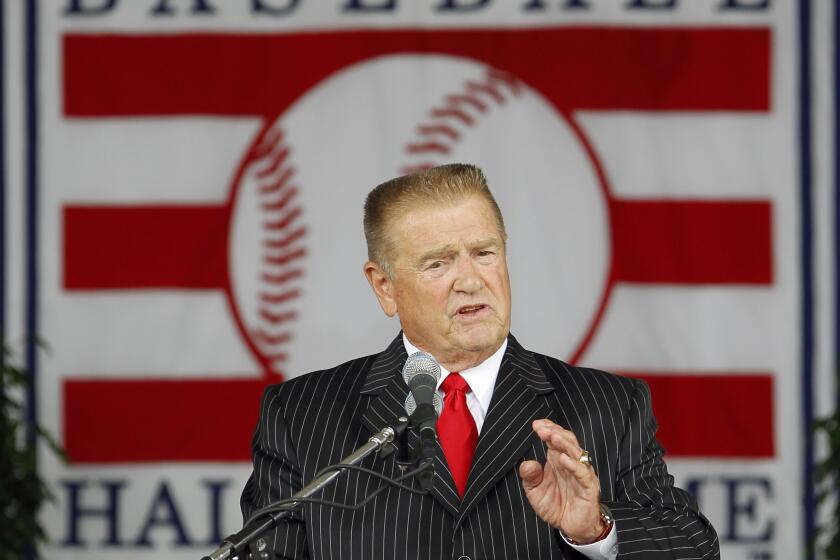

Frank Fenner dies at 95; microbiologist led the eradication of smallpox

Australian microbiologist Frank Fenner, who headed the World Health Organization team that eradicated the smallpox virus globally and who played a key role in reducing the 1950s plague of rabbits in Australia, died Monday, according to the Australian National University, where he had spent much of his career. He was 95, and no cause of death was released.

Fenner was a leading expert on three pox viruses: one that infects mice, one that infects rabbits and one that plagued humans. And along the way, he performed major work on controlling malaria.

“His contribution … to the nation, and indeed the world, is difficult to quantify because it is so wide-ranging,” ANU Vice Chancellor Ian Chubb said in a statement. Nobel laureate Peter Doherty, who won the 1996 prize in medicine, has often said Fenner should have received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work eradicating smallpox “because they sometimes give the peace prize for enormous practical achievements.”

Frank John Fenner was born Dec. 21, 1914, in Ballarat, Australia. He was interested in geology from an early age, but his father convinced him that medicine would provide a steadier source of income. He studied tropical medicine at the University of Adelaide, then enlisted in the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps in 1940.

Fenner was deployed to Palestine but was soon transferred to New Guinea, where malaria was ravaging the troops. Casualty rates from the disease were so high, authorities feared that Australia would be unable to continue fighting the Japanese. Largely through Fenner’s efforts, the disease was brought under control, and he was given partial credit for the country’s subsequent victory over Japan. He was made a Member of the British Empire for his achievement. At his request, the medal was awarded to his father.

After World War II he studied mousepox, a disease caused by the ectromelia virus, using it as a model for the incubation periods of infections such as smallpox, measles and chickenpox. That work was a primer for studying human diseases in animals.

After a fellowship at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, he was invited by Nobel laureate Howard Florey to head the department of microbiology at the Australian National University’s John Curtin School of Medical Research, where he began studying myxomatosis.

Australian farming communities had become overrun with more than 600 million rabbits because of the lack of natural predators, and the government was advocating the use of the myxomatosis virus to kill them off. In 1950, however, the virus escaped from one of four trial sites and spread rapidly across Australia’s Murray-Darling basin, killing millions of rabbits. At the same time, an encephalitis outbreak occurred among humans and panic ensued.

Fenner and two colleagues, confident that the virus could not replicate in humans, injected themselves with enough virus to kill 1,000 rabbits. When nothing happened to them, the panic subsided and the program continued.

Fenner’s research showed that the virus could kill only some of the rabbits and that the rest would develop immunity. That is what happened. Australia’s rabbit population never got below 100 million and is now more than 200 million.

In 1969, Fenner became an advisor to the WHO’s smallpox eradication program and in 1977 was appointed chairman, making regular field trips to trouble spots where eradication was proceeding slowly. On May 8, 1980, he announced at a World Health Assembly meeting that the disease had been eradicated — that there was no longer transmission from human to human.

Fenner’s wife of 51 years, Ellen “Bobby” Roberts, died in 1995. He is survived by a daughter, Marilyn; two grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.