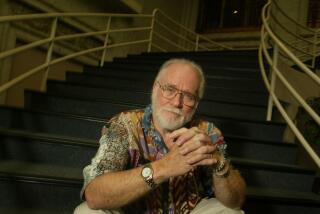

Jose Arguelles dies at 72; New Age thinker conceived 1987’s Harmonic Convergence

In 1983, art historian Jose Arguelles was driving down Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles to return a rental car when a vision bloomed: On Aug. 16, 1987, a critical mass of humanity would congregate at sacred spots around the world to bond with the cosmos and prevent global catastrophe.

FOR THE RECORD:

Jose Arguelles: The obituary in the April 10 California section on Jose Arguelles, who conceived the 1987 event called the harmonic convergence, said he taught at Evergreen State University. It is Evergreen State College. —

The theory behind the proposed happening was farfetched, involving extraterrestrial Mayans and synchronicity with the universe, but at sunrise on the appointed day, Arguelles’ call was answered. From Mt. Shasta in California and Central Park in New York to Machu Picchu in Peru and the Great Pyramids in Egypt, thousands of people danced, hugged, solar-charged their crystals and chanted “om.” Some searched the skies for UFOs. Arguelles, stationed at a campsite near Boulder, Colo., blew a conch shell 144 times.

Was the occasion a “moronic convergence… sort of a national fruit loops day,” as spoofed in the “Doonesbury” comic strip? Or was it the Harmonic Convergence, as Arguelles named the unusual event?

The only certainty was that Arguelles’ idea had resonated with a generation of seekers riding the New Age wave of the 1980s. Early in the decade, actress Shirley MacLaine’s assertions about reincarnation had helped stir mass curiosity about alternative spirituality, but Arguelles’ galactic be-in brought it to a peak. The harmonic convergence, J. Gordon Melton and James R. Lewis wrote in their book “Perspectives on the New Age,” attracted “more public attention than any New Age event before or since.”

Arguelles was planning another convergence for 2012 when he died March 23 at his retreat in central Australia. He was 72 and died of peritonitis, said his partner and research assistant, Stephanie South.

The foundation for the harmonic convergence was laid out in Arguelles’ 1987 book, “The Mayan Factor: Path Beyond Technology.” Based on his interpretation of the ancient Mayan calendar, he determined that Aug. 16-17 of 1987 offered a crucial window in planetary time to correct Earth’s “dissonances” and usher in the final 25 years of a 5,125-year cycle that would end in 2012. His book popularized the idea that 2012 would bring an epochal shift.

For the harmonic convergence to succeed, Arguelles said that “minimum human voltage” of 144,000 participants was needed. In the United States, some of the gatherings drew multitudes: 5,000 people on Mt. Shasta; another 5,000 in Sedona, Ariz.; 1,000 at Chaco Canyon, N.M.; and more than 1,500 in Central Park.

On the “Tonight” show, host Johnny Carson quipped, “I hear that there are only 143,500, but there are 500 of us in the audience, so let’s all take a moment and ‘om.’”

Academics skewered Arguelles as a crackpot and said his understanding of Mayan cosmology was seriously flawed. “Although I have spent years studying Mesoamerican calendars,” Colgate University astronomy professor and Maya expert Anthony Aveni wrote, “I must confess that I cannot understand even one of Arguelles’ complicated-looking diagrams. Nor can I follow his explanation, which … is punctuated with scientific jargon incomprehensible even to scientists.”

Post-convergence, analysts searched for signs of change. Over the next two years, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed glasnost, democracy demonstrators rocked China’s Tiananmen Square and Playboy founder Hugh Hefner got married, but whether these events were evidence of a cosmic reboot could not be determined.

Two months after the convergence, Arguelles’ 18-year-old son, Josh, was killed in a car accident. The tragedy did not lessen his belief that the harmonic convergence was working. “Whether people understood it or not,” he said, “they felt the signal — it was on the level of when a species gets a signal to change its migration pattern.”

His signal to change came early. Born in Rochester, Minn., on Jan. 24, 1939, to a German American mother and a Mexican father, Arguelles lived in Mexico for several years, moving back to Minnesota when he was 7. Wounded by anti-Mexican prejudice, he stopped speaking Spanish and assimilated, a course he maintained until 1953. That year he visited the pyramids of Teotihuacán outside Mexico City and felt a “profound sentiment” to reconnect with his roots. He began to study the Mayan calendar and eventually would campaign to replace the Gregorian calendar, which he regarded as a primary cause of the world’s ills, with his own 13-month system.

After earning a doctorate in art history in 1969 from the University of Chicago, Arguelles became an academic, teaching briefly at Princeton before moving on to UC Davis and later to Washington’s Evergreen State University. At Davis, he helped organize an “art happening” that led in 1971 to the first Whole Earth Festival, now in its 40th year.

Arguelles viewed the recent spate of earthquakes, tsunamis and wars as the buildup to 2012, but he was not a doomsdayer. He anticipated a rosier “galactic age” in which people would return to a simpler lifestyle and communicate by telepathy.

“Something is going to happen,” he wrote not long ago. But the adventure will unfold without one of its wilder dreamers.

Arguelles, who had homes in Ashland, Ore., and Palenque, Mexico, was divorced three times. In addition to South, he is survived by a daughter, Tara; a twin brother, Ivan; and a sister, Laurita Kinsley.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.