PASSINGS: Magic Slim, Cleotha Staples, Lou Myers, Donald Rutledge

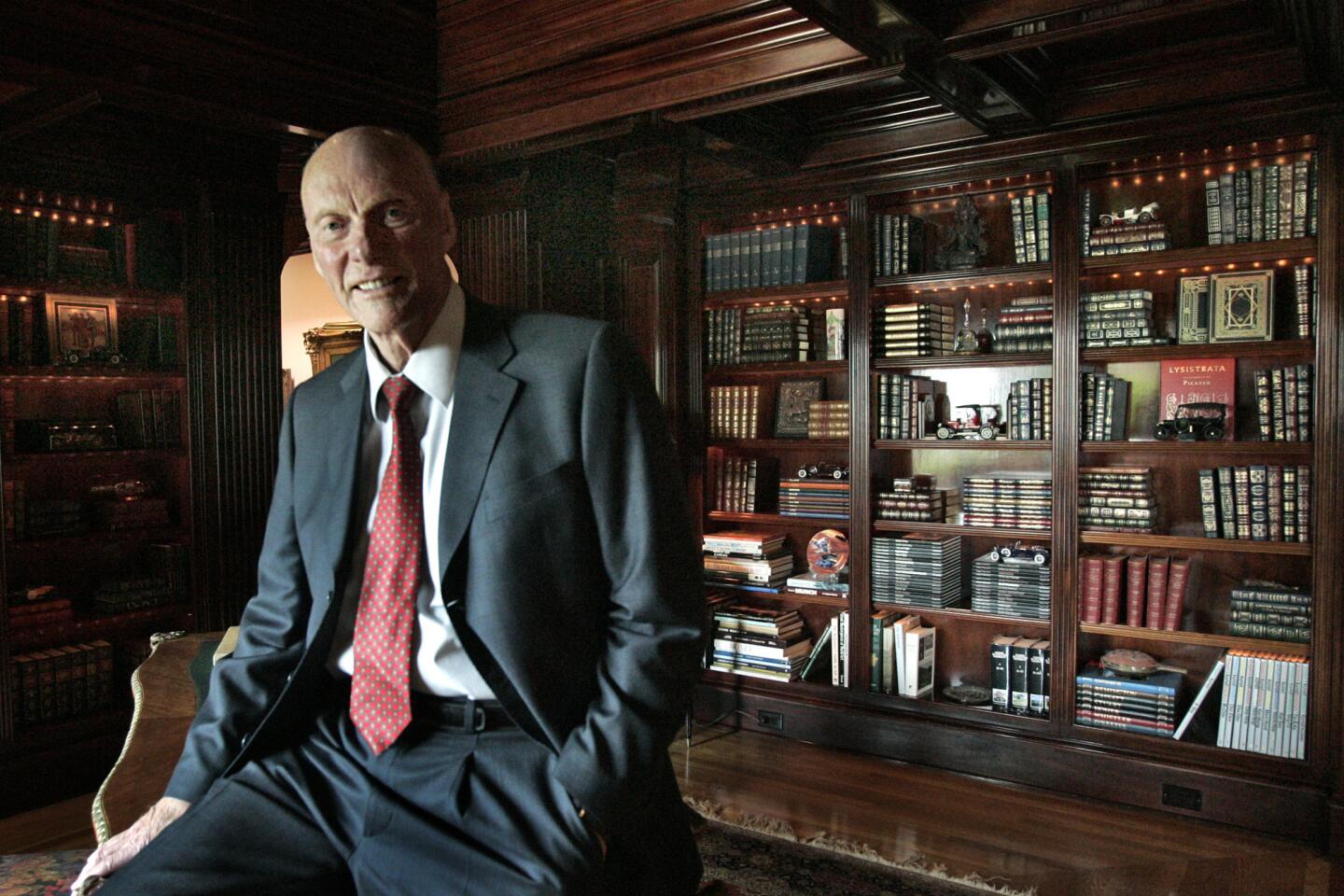

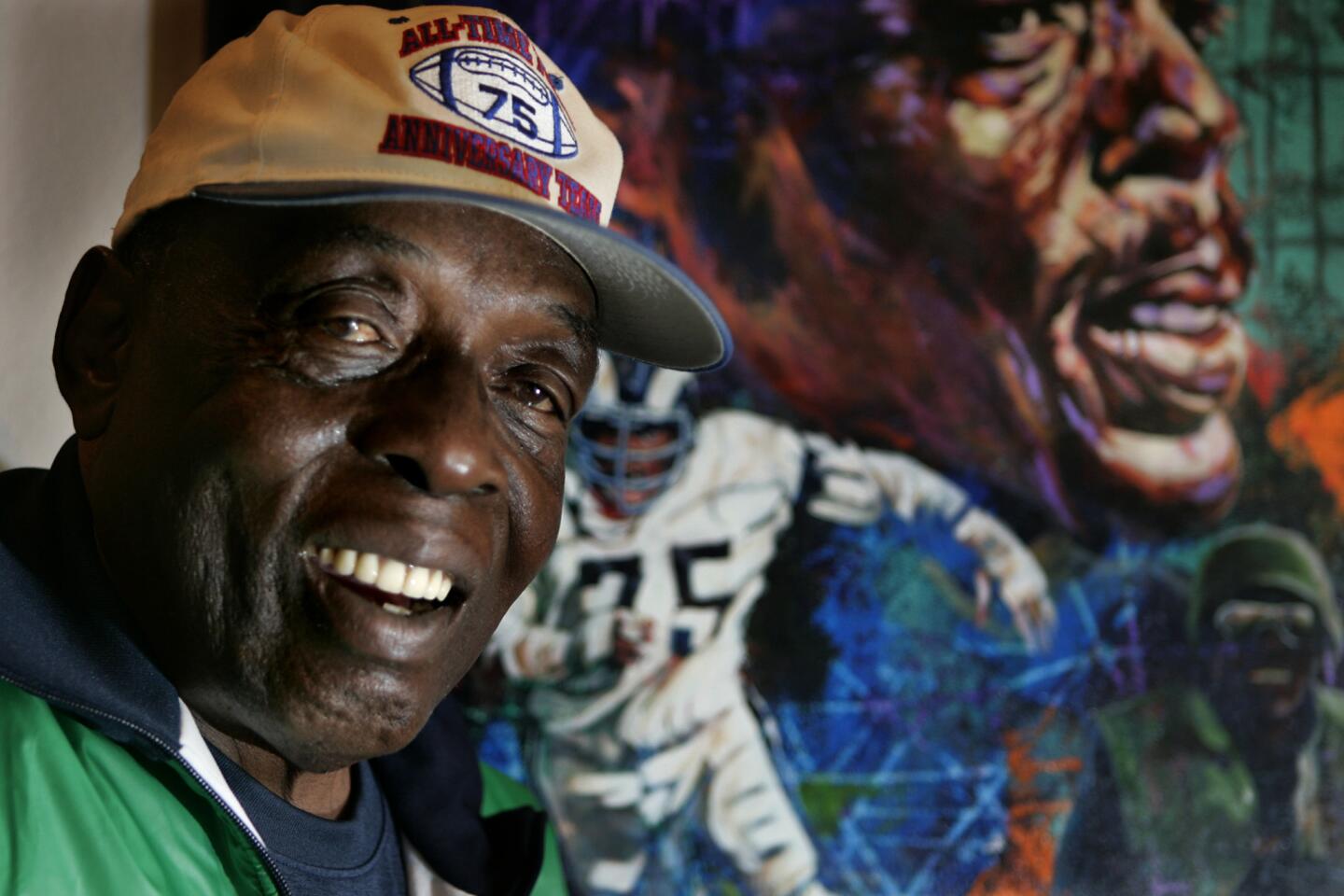

Magic Slim

Singer of Chicago blues

Magic Slim, 75, whose ragged voice and punchy guitar riffs made him a symbol of Chicago blues, died Thursday in Philadelphia after surgery for a bleeding ulcer, according to his family.

A younger contemporary of blues icons Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, Slim and his backup band, the Teardrops, were known for a no-holds-barred style of Chicago electric blues.

“If you were going to take somebody who’d never seen blues to one of their shows, it would be like putting them in a time machine and putting them in 1962. No frills, no rock ‘n’ roll. It was just straight-ahead, real-deal blues,” said Marty Salzman, Slim’s manager.

FOR THE RECORD:

Lou Myers obituary: An obituary of actor Lou Myers in the Feb. 25 LATExtra section reported his date of birth as Sept. 26, 1945, and his age as 76. He was born Sept. 26, 1935, and was 77 when he died.

Born Morris Holt in Torrance, Miss., on Aug. 7, 1937, he worked in the cotton fields as a child and made his own guitar out of baling wire nailed to a wall. He also tried piano but switched back to guitar after he lost a little finger in a cotton-gin accident.

One of his earliest musical influences was Sam Maghett, who was known professionally as Magic Sam when he became a Chicago blues star in the 1960s. The two met after Morris moved to Grenada, Miss., when he was 11 and started jamming together on Sundays after church. In 1955, Morris followed his friend to Chicago, where Sam anointed him Magic Slim, a reference to Morris’ height, which exceeded 6 feet, and gave him his first job as a bass player.

He was spurned by Chicago’s blues players, who didn’t think he was good enough to join their sessions, so he returned to Mississippi to hone his skills. After five years, “I came back,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1996, and announced, “All right, I’m ready for y’all now!”

In 1966 he recorded his first single, “Scufflin.” The next year he recruited his younger brothers, Nick and Douglas, to form the Teardrops and was on his way to becoming a Chicago institution. He cut his first album, “Born Under a Bad Sign,” for a French label in 1977. Later he recorded regularly for Alligator Records, Rooster Blues, Wolf Records and Blind Pig Records.

He and the Teardrops won the Blues Music Award for blues band of the year in 2003. In his 70s he remained active on the music festival circuit and won critical praise for his recordings, which included “Black Tornado” (1998), “Snakebite” (2000), “Raising the Bar” (2010) and “Bad Boy” (2012).

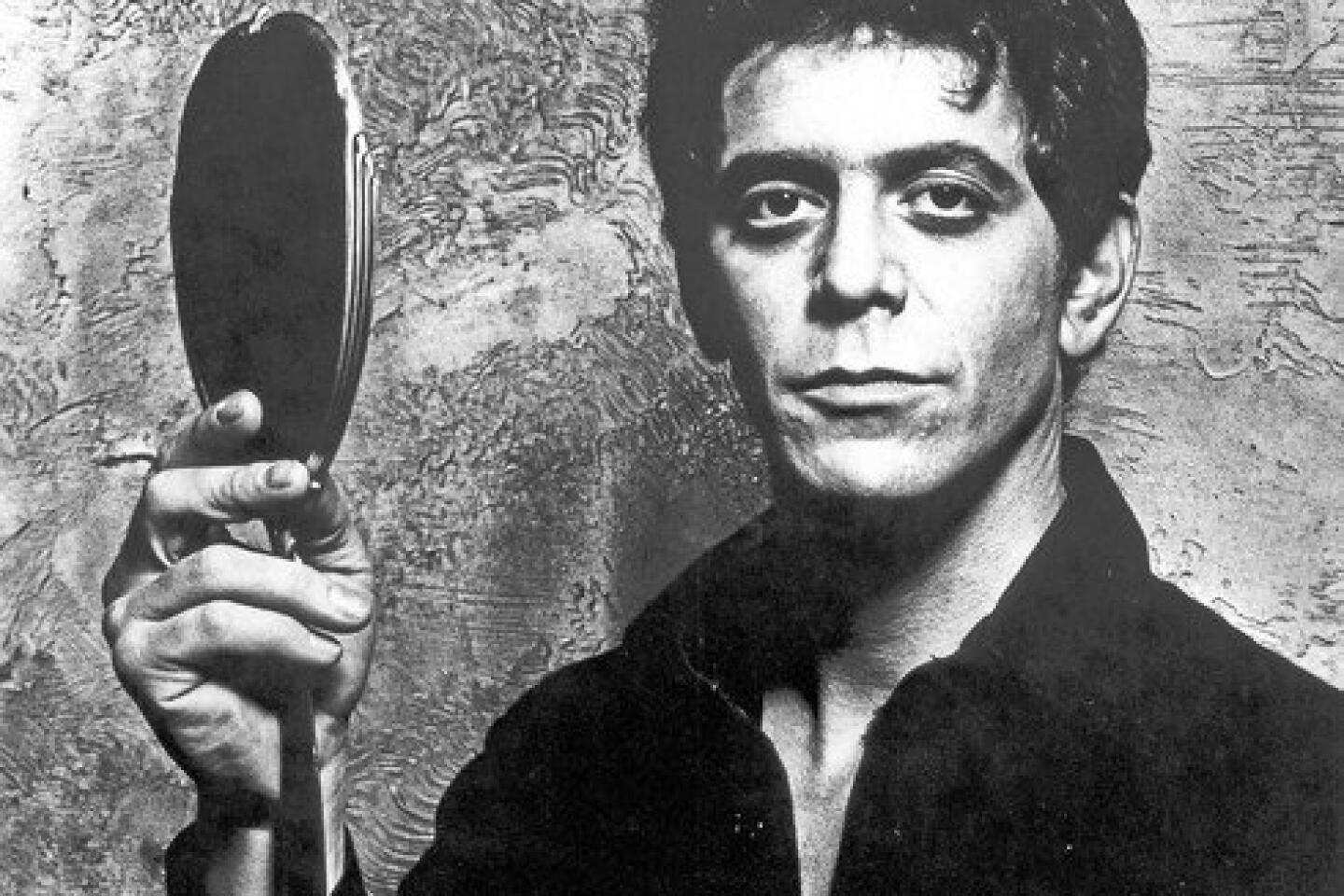

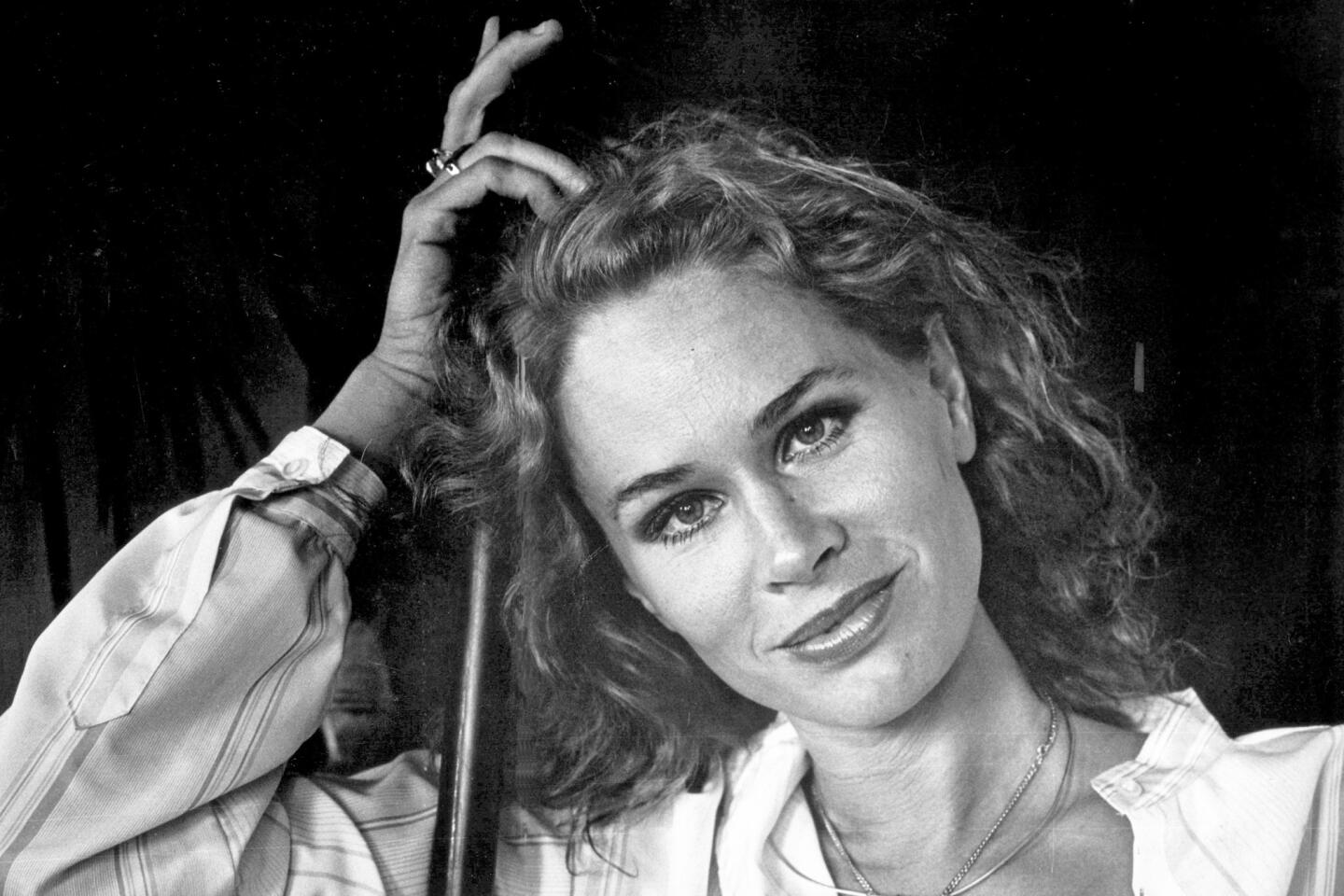

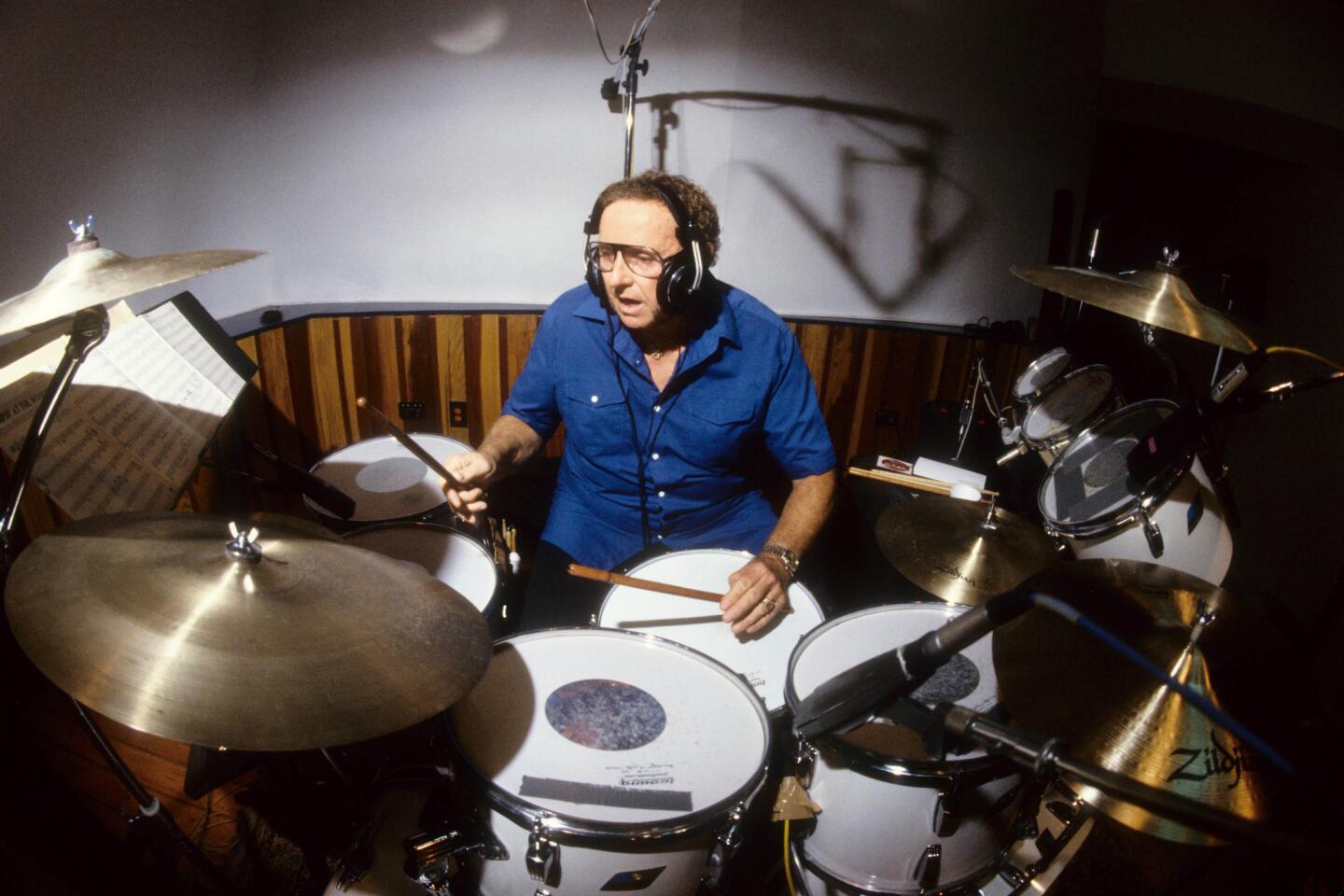

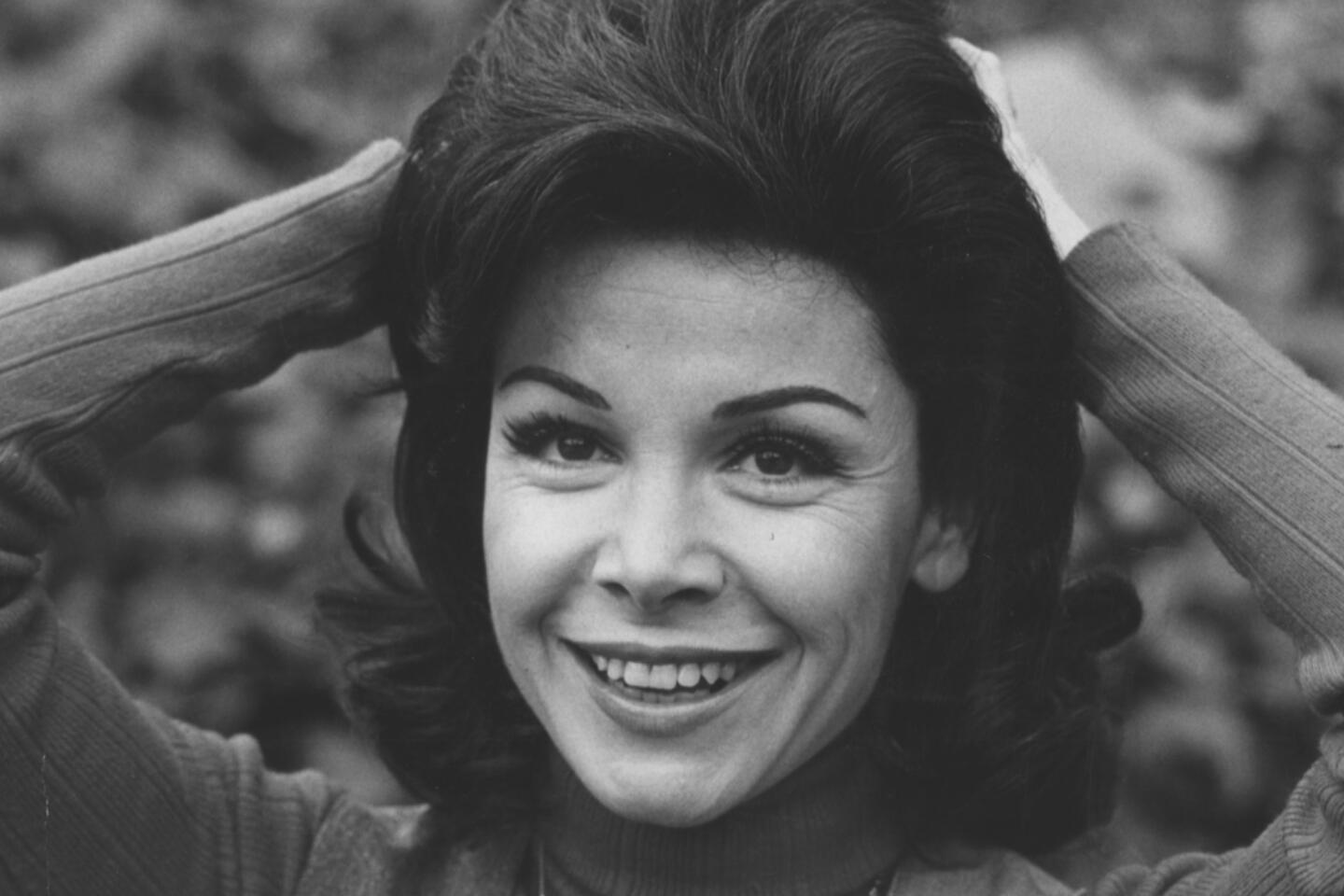

Cleotha Staples

Co-founder of soul and gospel group

Cleotha Staples, 78, a founding member of the soul and gospel group The Staple Singers, died Thurday at her Chicago home, her sister, Mavis Staples, said.

A specific cause was not disclosed but Staples had been diagnosed with Alzheimers disease more than 10 years ago.

The group organized in the 1940s by her father, Roebuck “Pops” Staples, consisted of five siblings, of whom Cleotha was the eldest. The others, in addition to Mavis were Pervis, Yvonne and Cynthia.

Mavis Staples credited her father’s guitar and Cleotha’s voice as key elements in the distinctive sound of the group, which sold tens of millions of records with hits such as “I’ll Take You There,” “Respect Yourself” and “Uncloudy Day.”

“A lot of singers would try to sing like her,” Mavis Staples said in a statement. “Her voice would just ring in your ear. It was’t harsh or hitting you hard, it was soothing. She gave us that country sound.”

Staples, who was nicknamed “Cleedi,” was admitted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with her family in 1999 and received a lifetime achievement award at the 2005 Grammy awards.

She was born in April 11, 1934, in Drew, Miss., and moved with her family to Chicago when she was 2. Her mother, Oceola, worked in a hotel and her father was a manual laborer who sang in gospel groups when he was young.

In the late 1940s, he started teaching his children the songs he learned as a child and formed a group with Cleotha, Mavis and their brother Pervis that performed in Chicago churches. By the early 1950s, they were cutting records and touring the country.

Cleotha Staples retired soon after her father died in 2000.

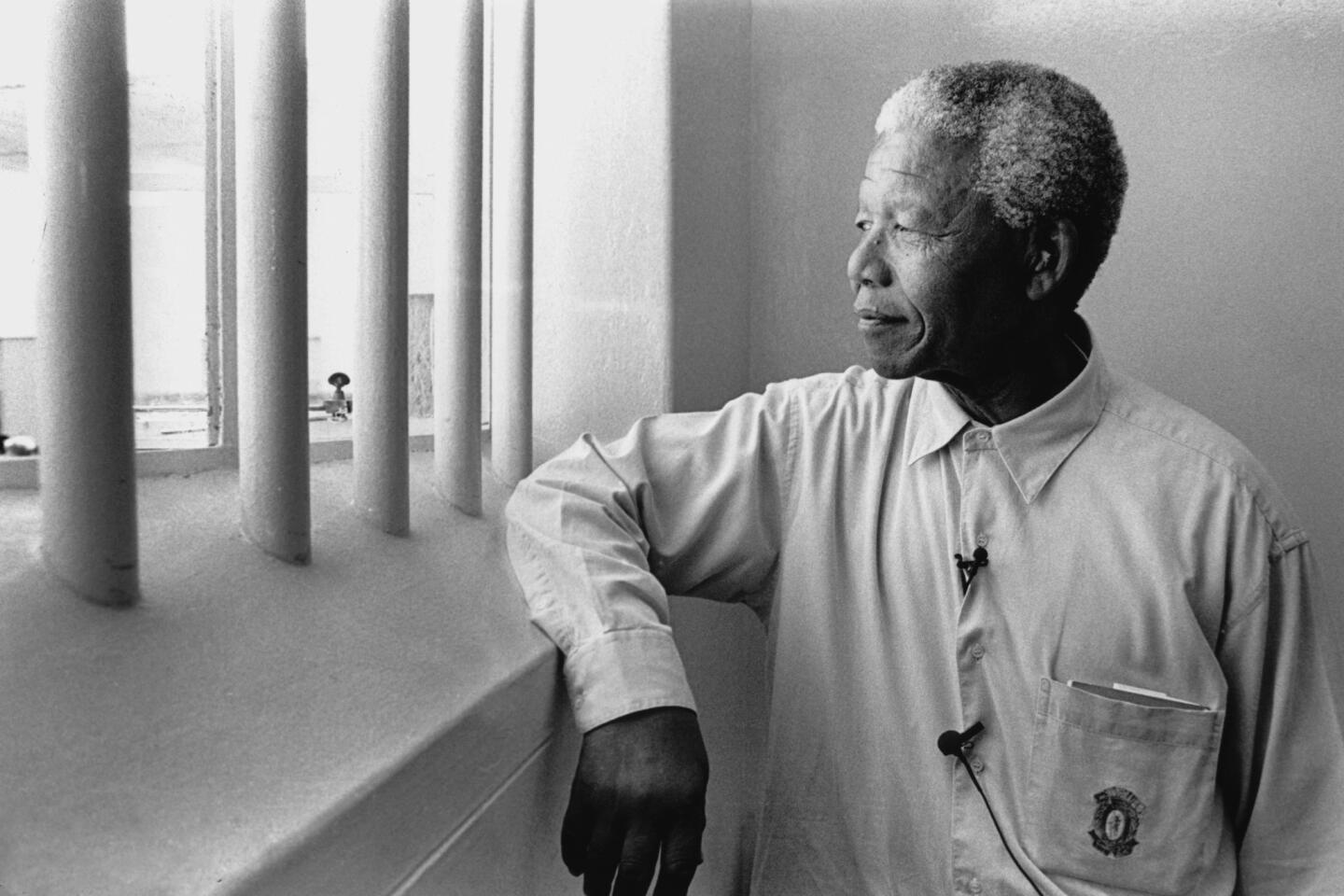

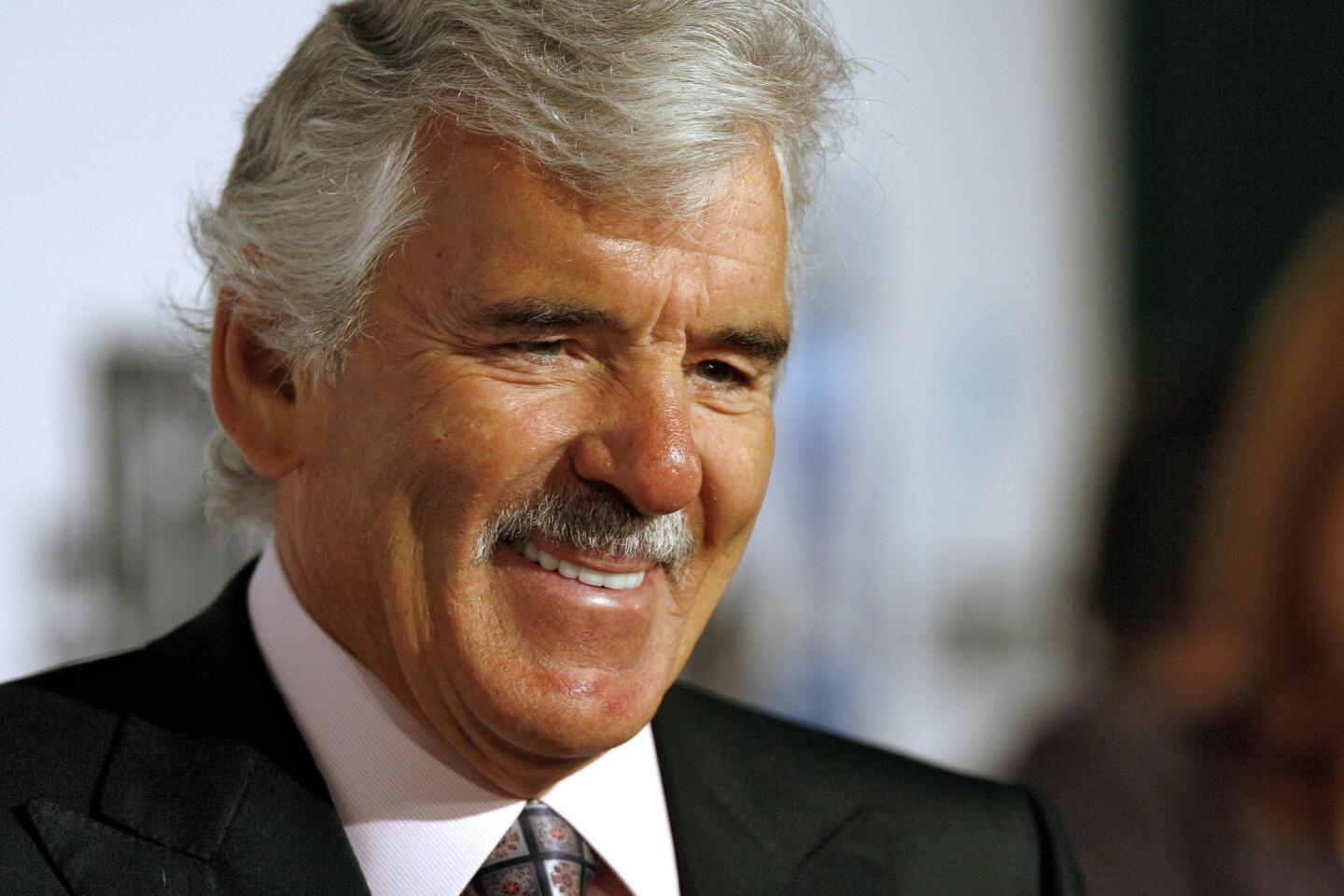

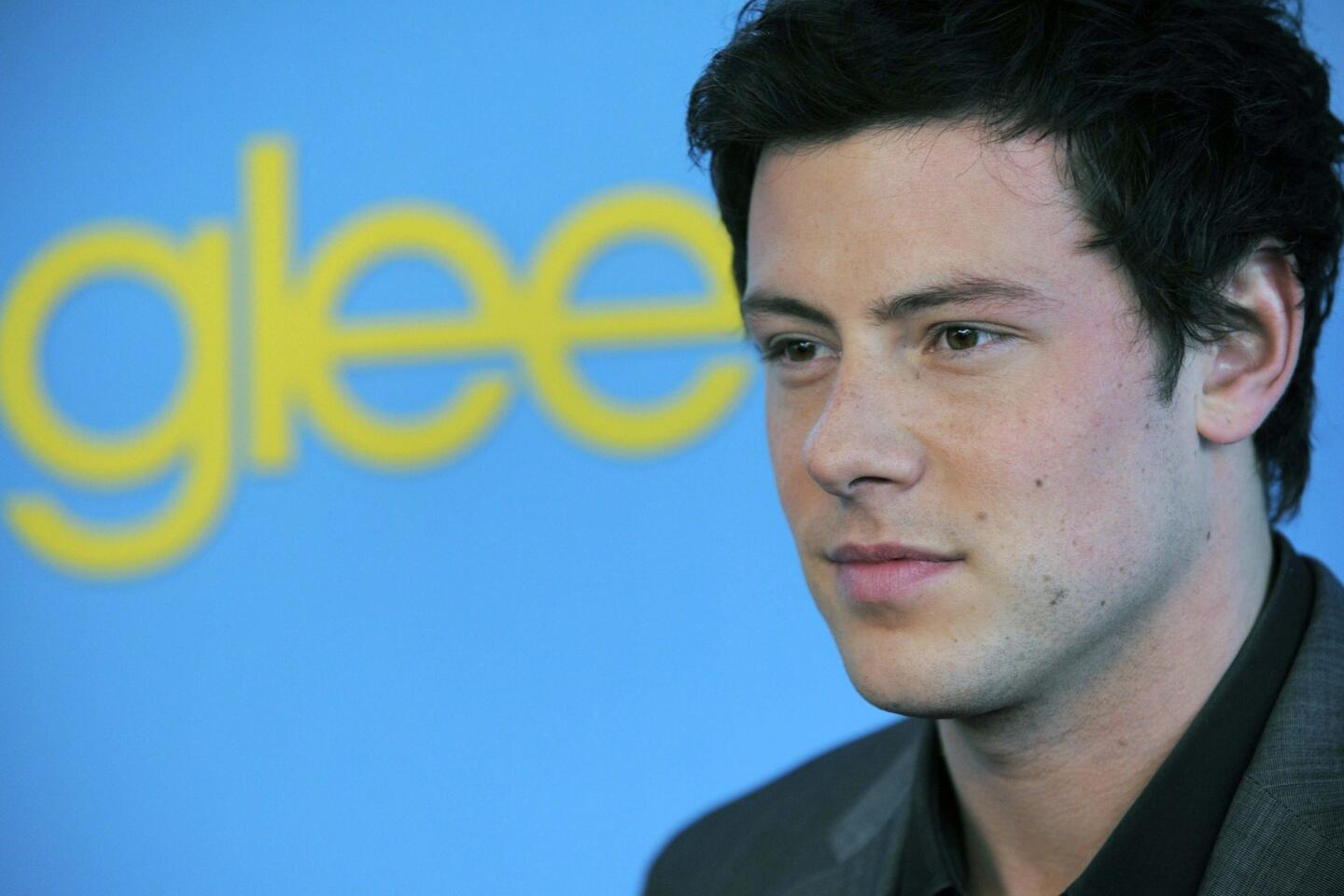

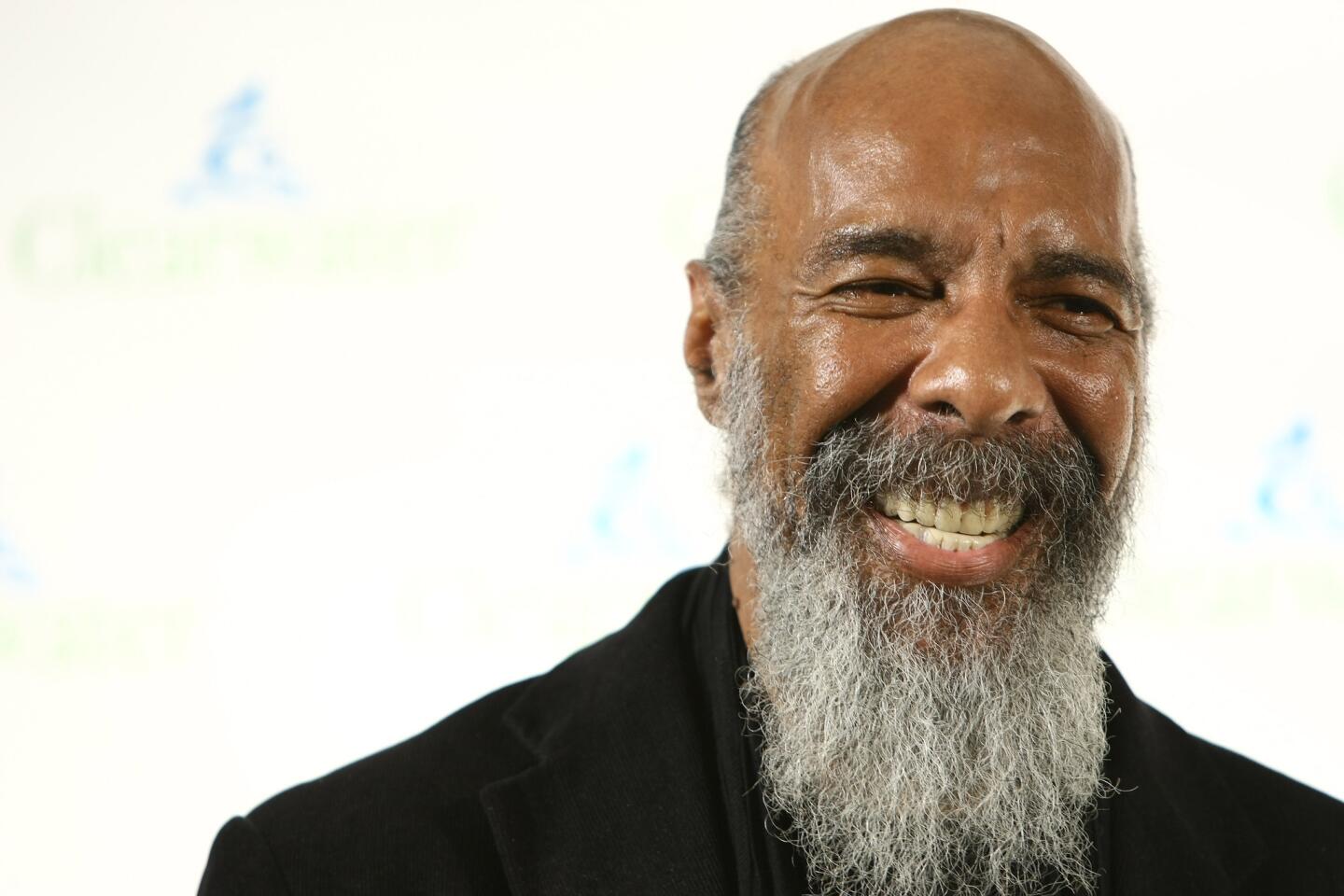

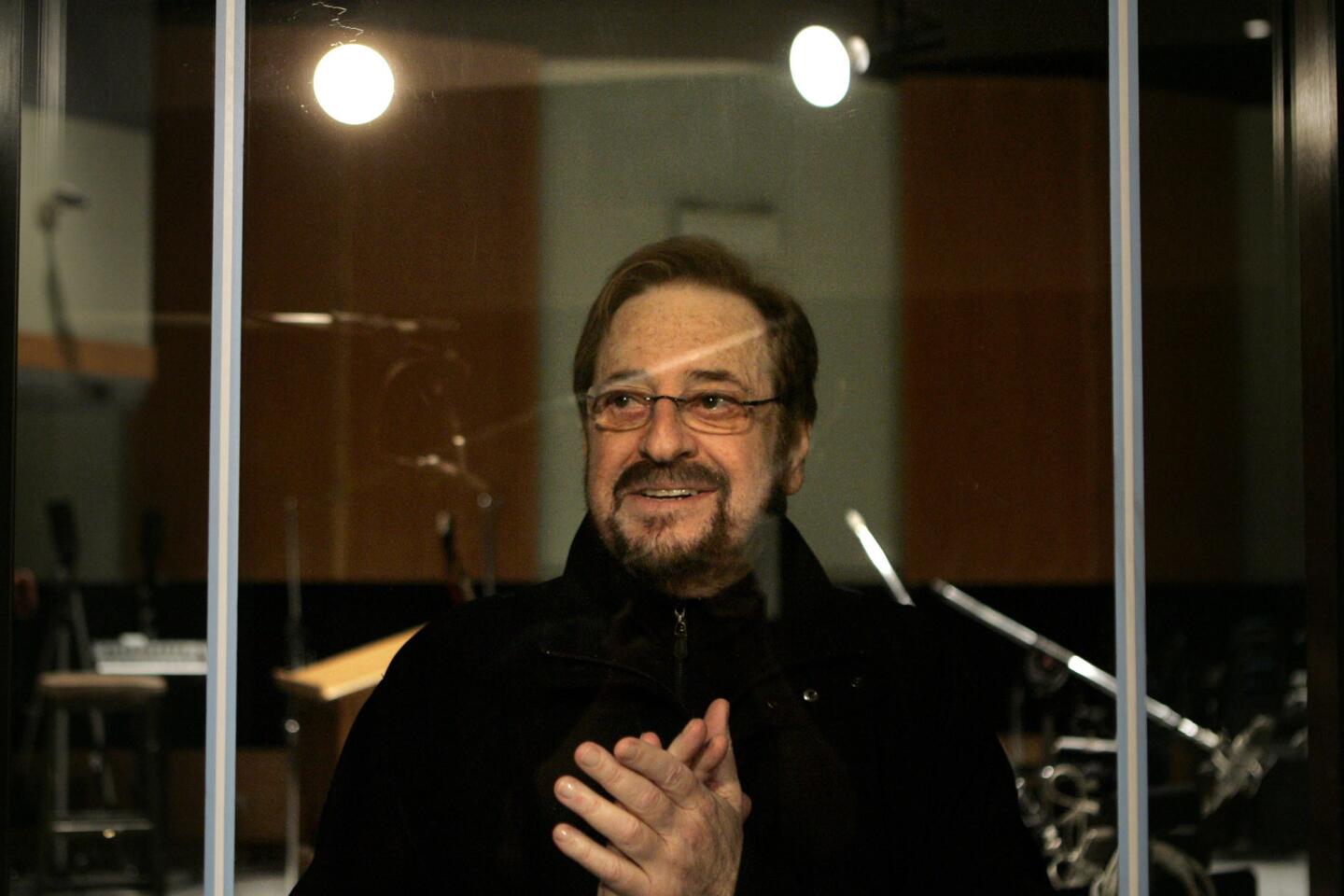

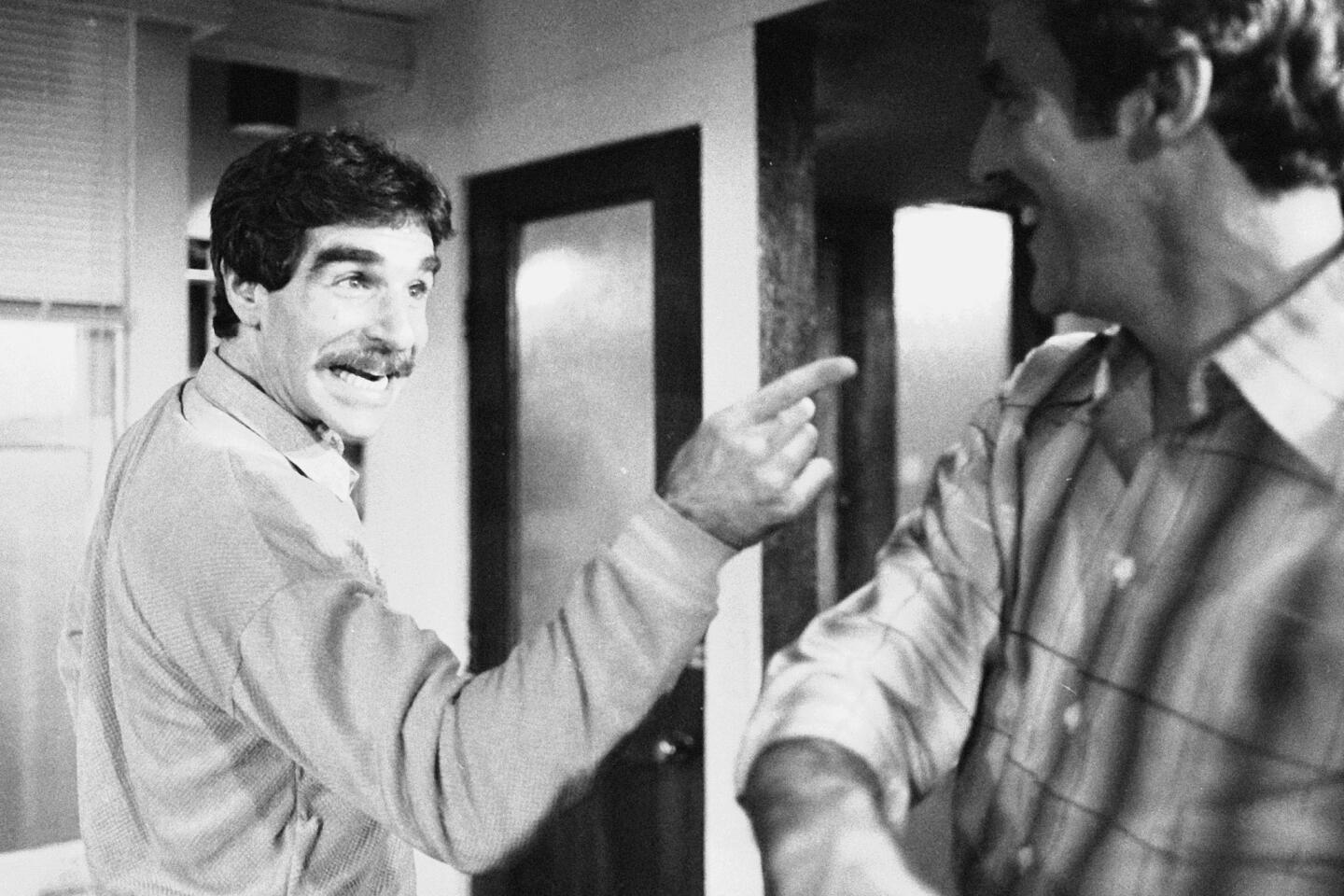

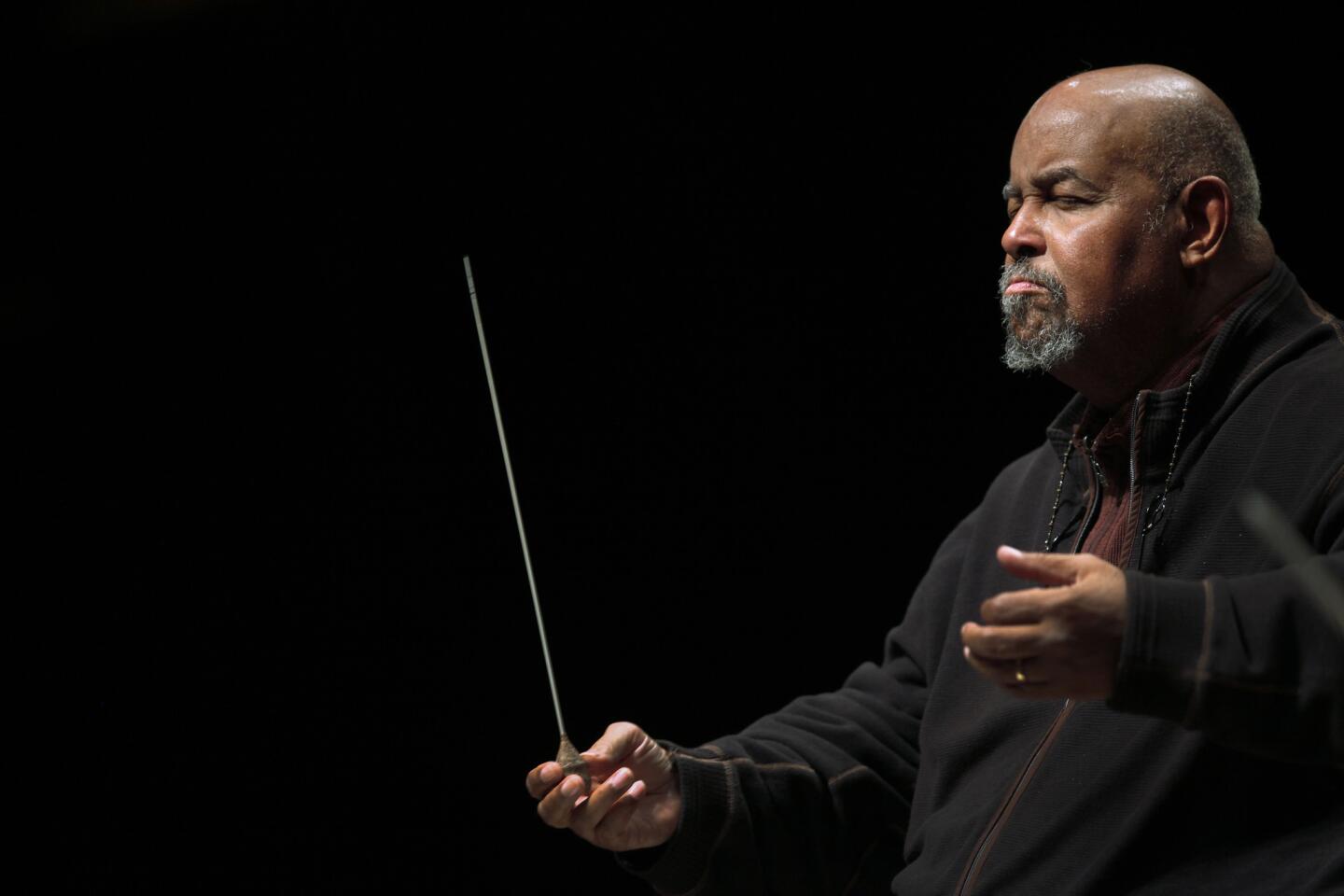

Lou Myers

Actor on ‘A Different World’

Lou Myers, 76, an actor perhaps best known for portraying ornery restaurant owner Mr. Gaines on the early 1990s sitcom “A Different World,” died Tuesday at Charleston Area Medical Center in West Virginia, according to a family spokeswoman. Myers had been in and out of the hospital since December. An autopsy was planned.

After Bill Cosby gave him the first of his TV guest roles on “The Cosby Show,” he became a regular on “A Different World,” which ran from 1987 to 1993 and originally starred Lisa Bonet from “Cosby.”

Myers’ films included “Tin Cup” (1996), “How Stella Got Her Groove Back” (1998) and “The Wedding Planner” (2001).

On Broadway, he appeared in a 2008 all-black production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” a staging of “The Color Purple” that opened in 2005, the original 1990 Broadway production of August Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson” and “The First Breeze of Summer” (1975).

Myers also played Wining Boy in “The Piano Lesson” at the James A. Doolittle Theatre in Hollywood in 1990 and in a 1995 TV movie production of the play; and Stool Pigeon in Wilson’s “King Hedley II” at the Mark Taper Forum in 2000.

He began singing jazz and blues with a touring company, “Negro Music in Vogue,” and brought his cabaret show to the Cinegrill in Hollywood.

Born Sept. 26, 1945, in Chesapeake, W.Va., Myers received a bachelor’s degree in sociology from West Virginia State University and a master’s in theater from New York University. In recent years, he chaired Global Business Incubation, which helps urban small businesses, and the Lou Myers Scenario Motion Picture Institute/Theatre, which produces shows.

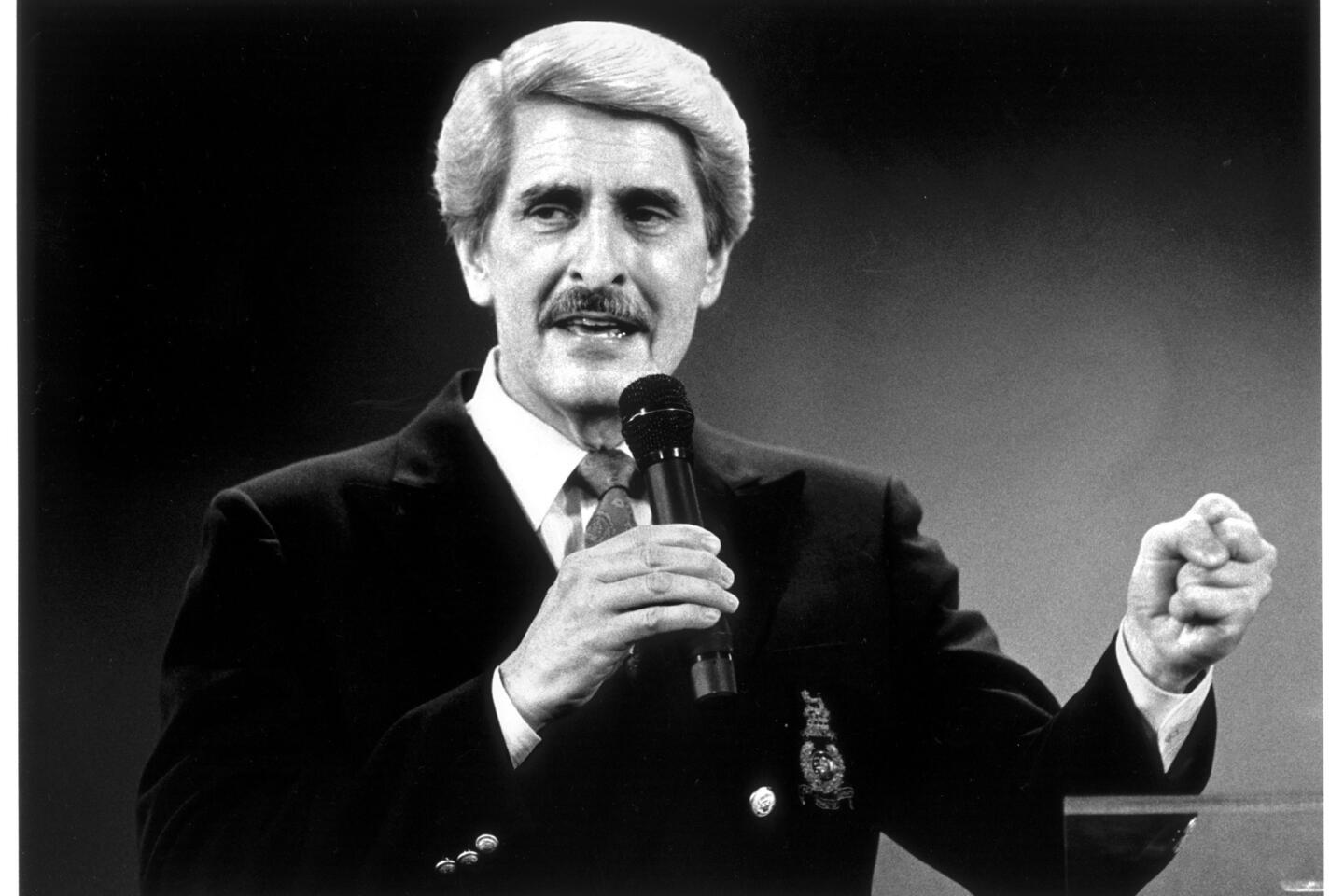

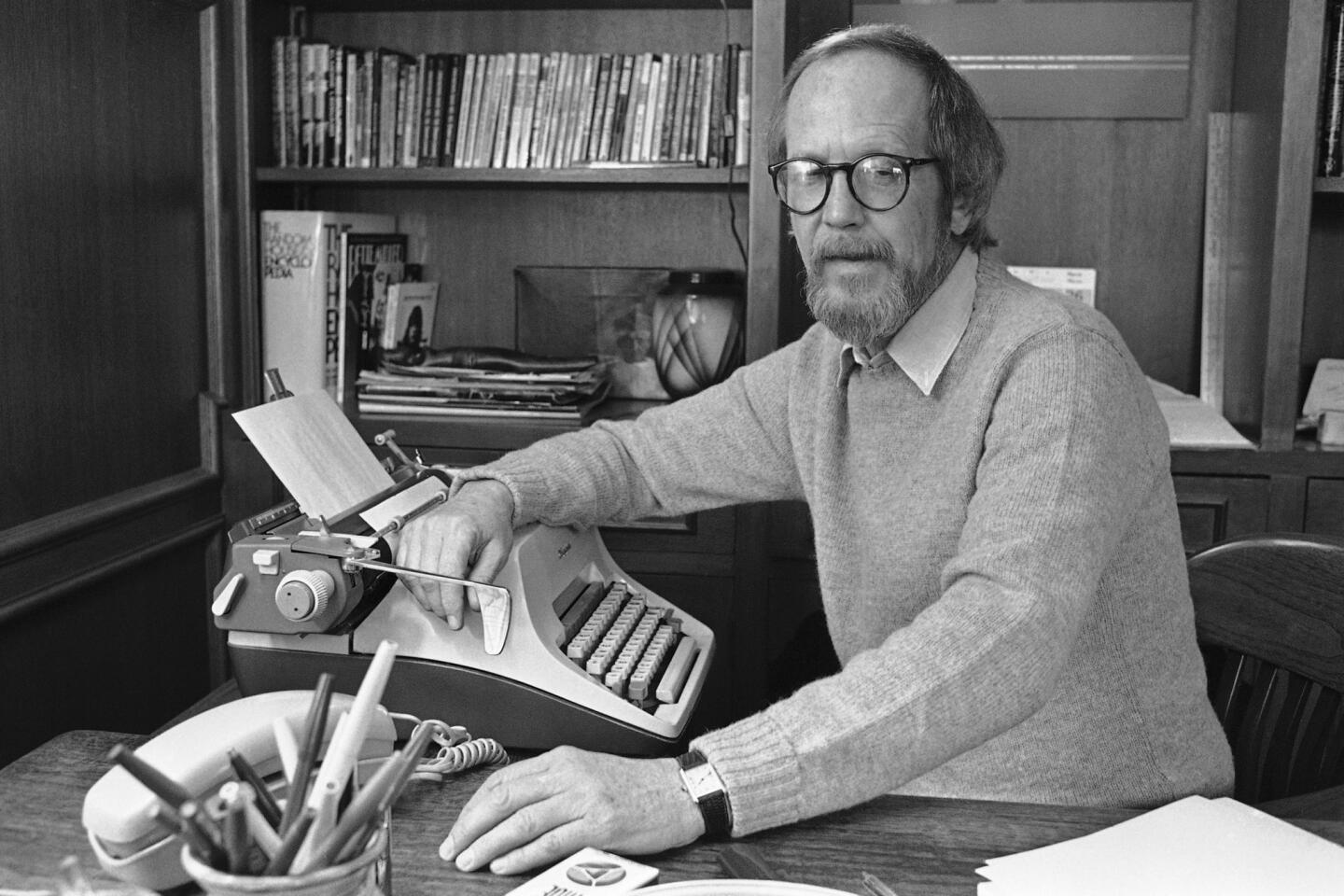

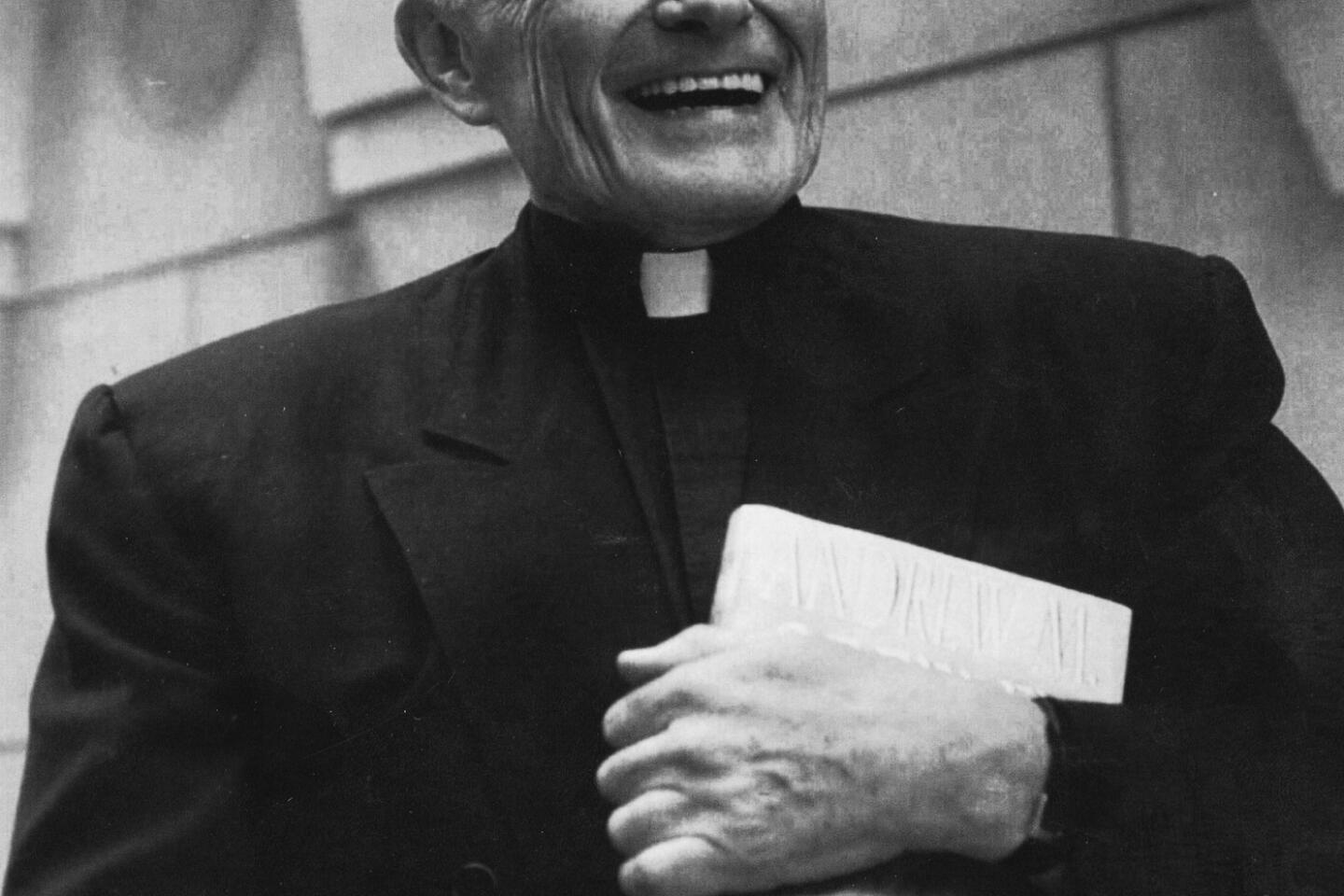

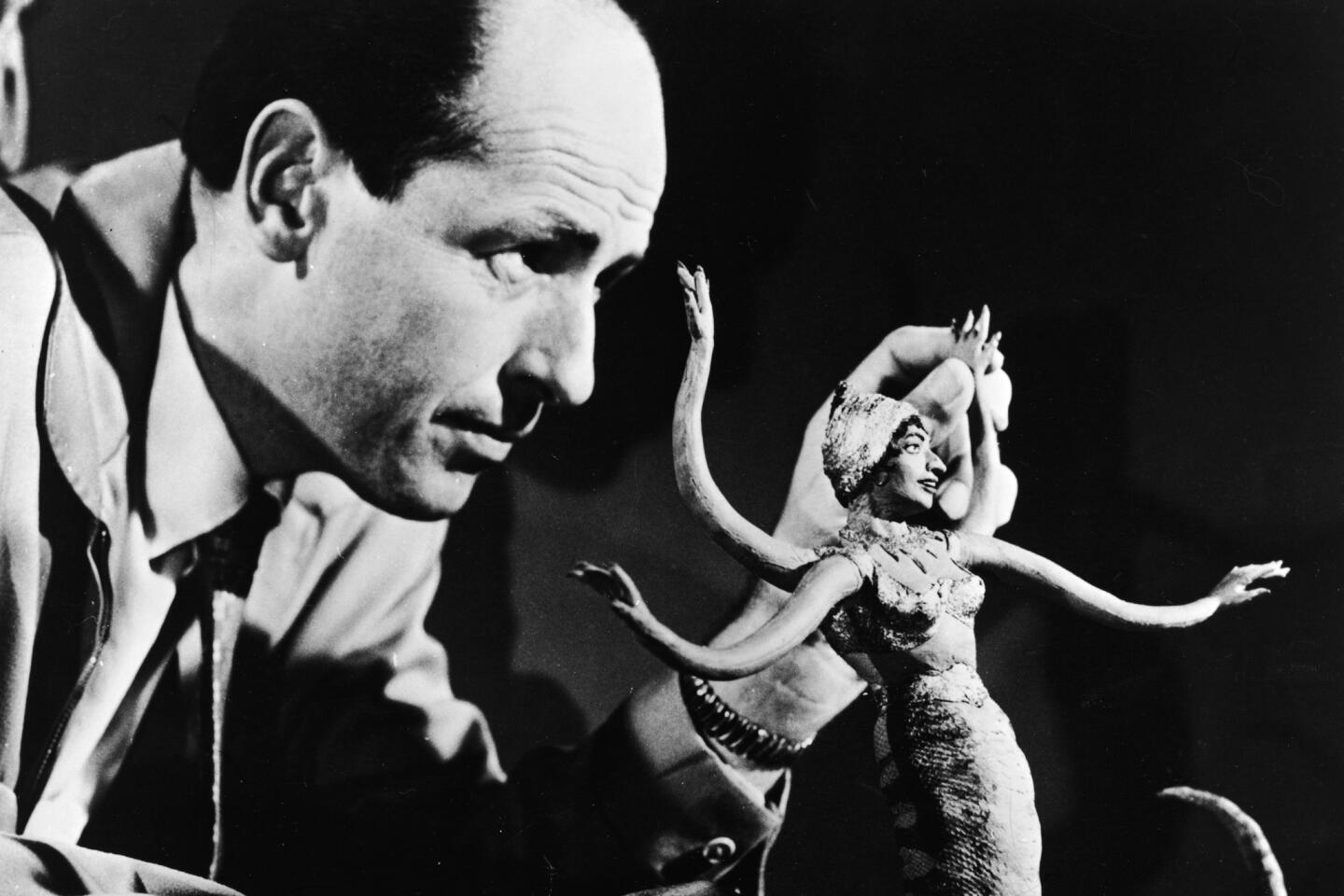

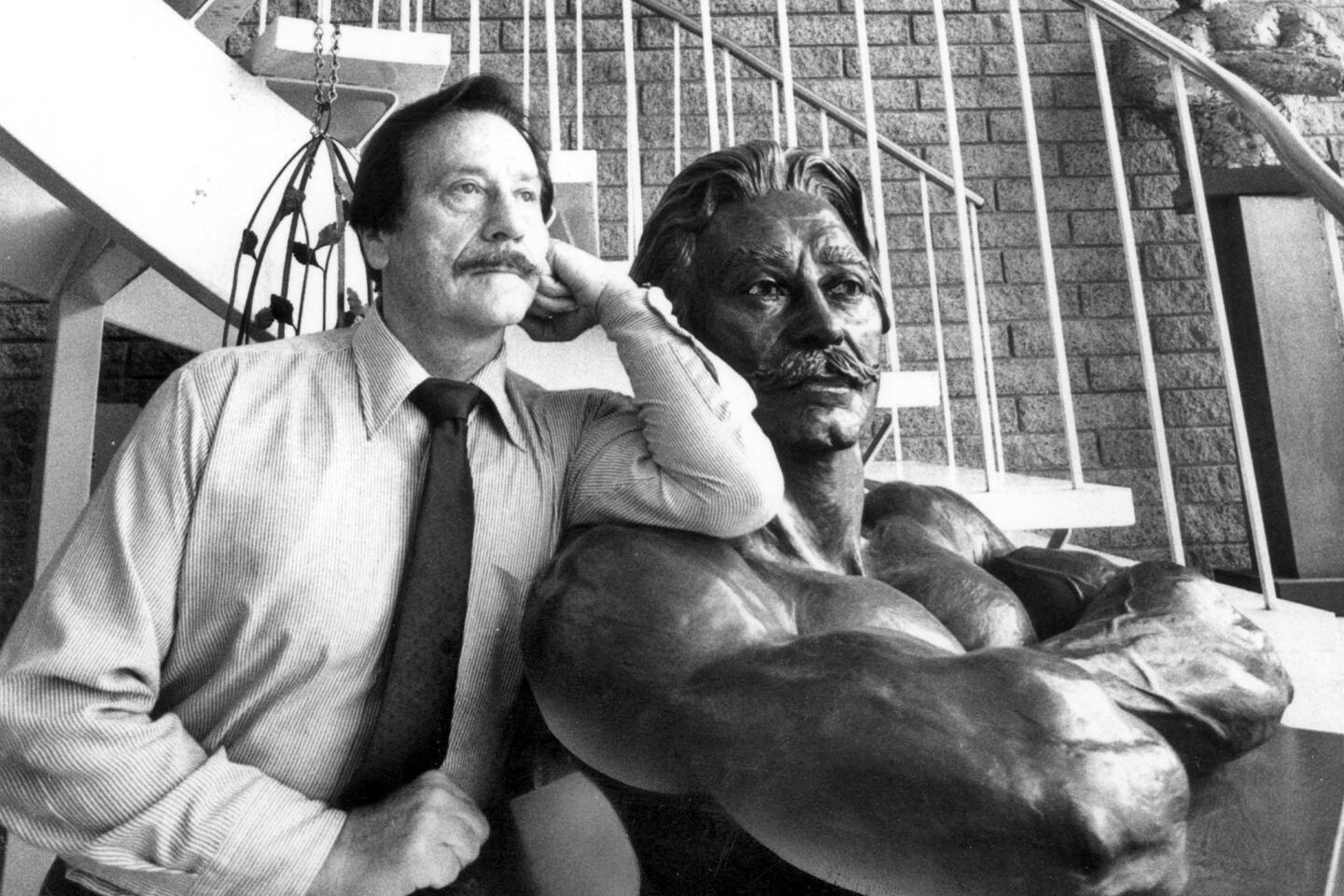

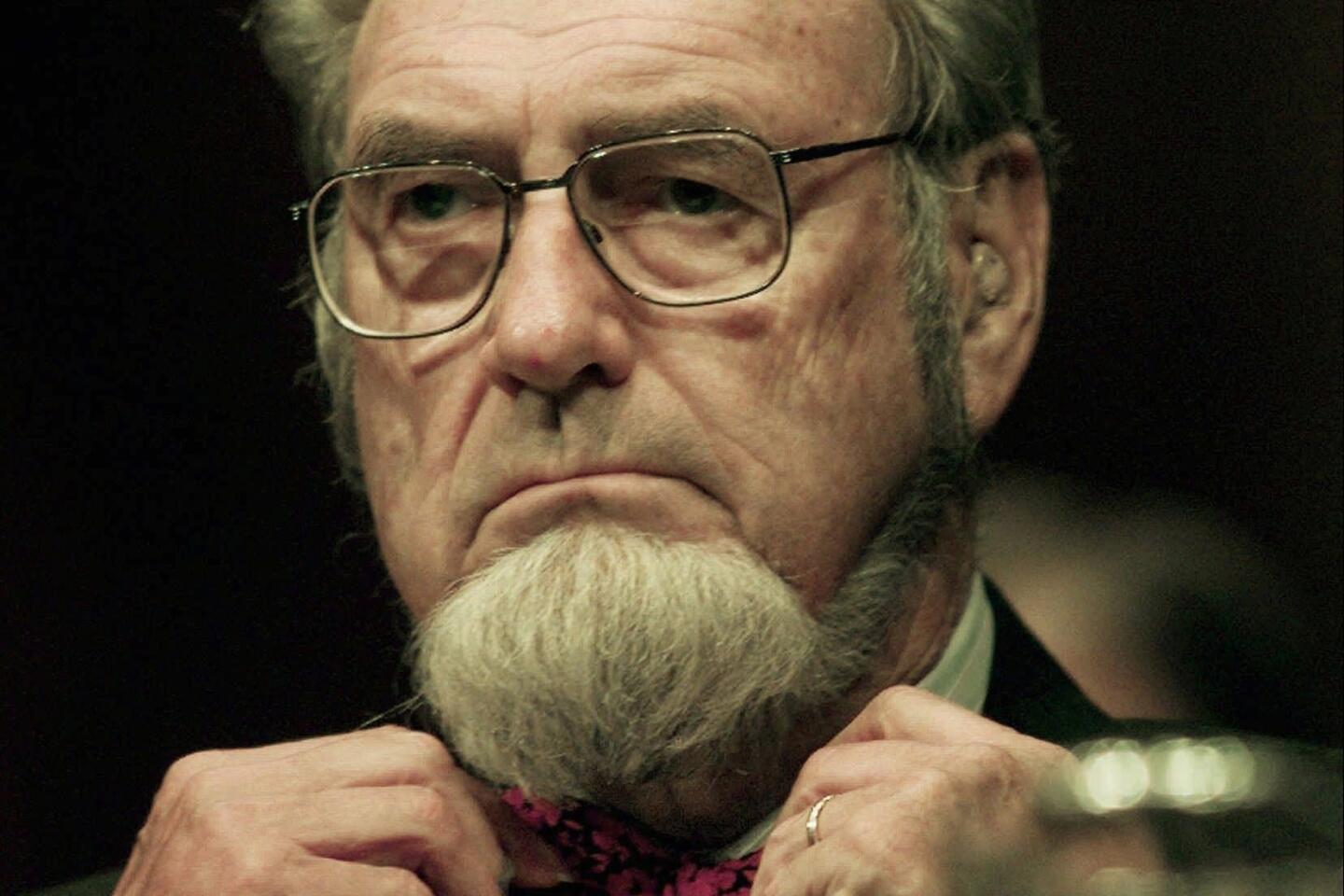

Donald Rutledge

Photographer known for Jim Crow-era images

Donald “Don” Rutledge, 82, a photographer acclaimed for his images of a white journalist disguised as a black man in the Jim Crow-era South, died Tuesday in Richmond, Va., his wife Lucy Marie Rutledge said. The cause was not disclosed.

Rutledge gained national prominence with his photographs for John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book “Black Like Me” about Griffin’s experiences of racism in the Deep South during the civil rights era. Griffin chemically darkened his skin to appear black and wrote about the fear and prejudice he experienced as a black man under segregation. Rutledge’s photos of Griffin’s social experiment helped make the book one of the most famous chronicles of the struggle for racial equality in the 1960s.

Rutledge, who was white, grew up in Smithville, Tenn., and became a Baptist minister after high school. He loved photography, however, and sold photos to United Press International before the prestigious Black Star photojournalism agency hired him.

The collaboration with Griffin arose after Rutledge pitched a story to Black Star for which he would photograph the largest group of black billionaires in the country, who all had offices on a single street in Atlanta. Black Star liked the idea and assigned Griffin as the writer.

When Rutledge learned of Griffin’s plan to travel the South as a black man, he joined him for the six-week journey through Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana. The book became a sensation and won Rutledge a full-time position with Black Star.

Rutledge later spent three decades photographing Baptist mission work in the United States and abroad. He also produced three books during that time.

In 1980, he went to work as a photographer for Foreign Mission Board, where he continued his photo ministry, primarily for The Commission magazine, until his retirement in 1996.

Rutledge continued to do some freelance work in the U.S. and abroad until suffering a stroke in 2001.

“I love photojournalism and enjoy using it as a worldwide Christian ministry,” he once wrote. “It helps me translate the national and international ministries into human terms by telling the story through people rather than through statistics.”

-- Los Angeles Times staff and wire reports

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.