Stephen E. Toulmin dies at 87; USC philosopher developed a model for building an effective argument

Stephen E. Toulmin, a British-born philosopher and retired USC professor who created a model for evaluating the practical arguments that arise from daily life during a six-decade career that brought him prominence in several fields, has died. He was 87.

Toulmin, who was the Henry R. Luce professor at the Center for Multiethnic and Transnational Studies, died Dec. 4 at USC University Hospital, said his son, Greg. The cause was pneumonia.

The Oxford-trained theorist was best known for “The Uses of Argument,” published in 1958 and still in print, which set forth six criteria for building an effective argument. It reflected his belief that philosophers should concentrate less on abstractions and more on real-world issues, such as medical ethics and environmentalism.

“It is time for philosophers to come out of their self-imposed isolation and reenter the collective world of practical life and shared human problems,” Toulmin once wrote.

He embraced this view in a literal way: by living with 550 students in a campus dormitory for almost a decade, until 2003.

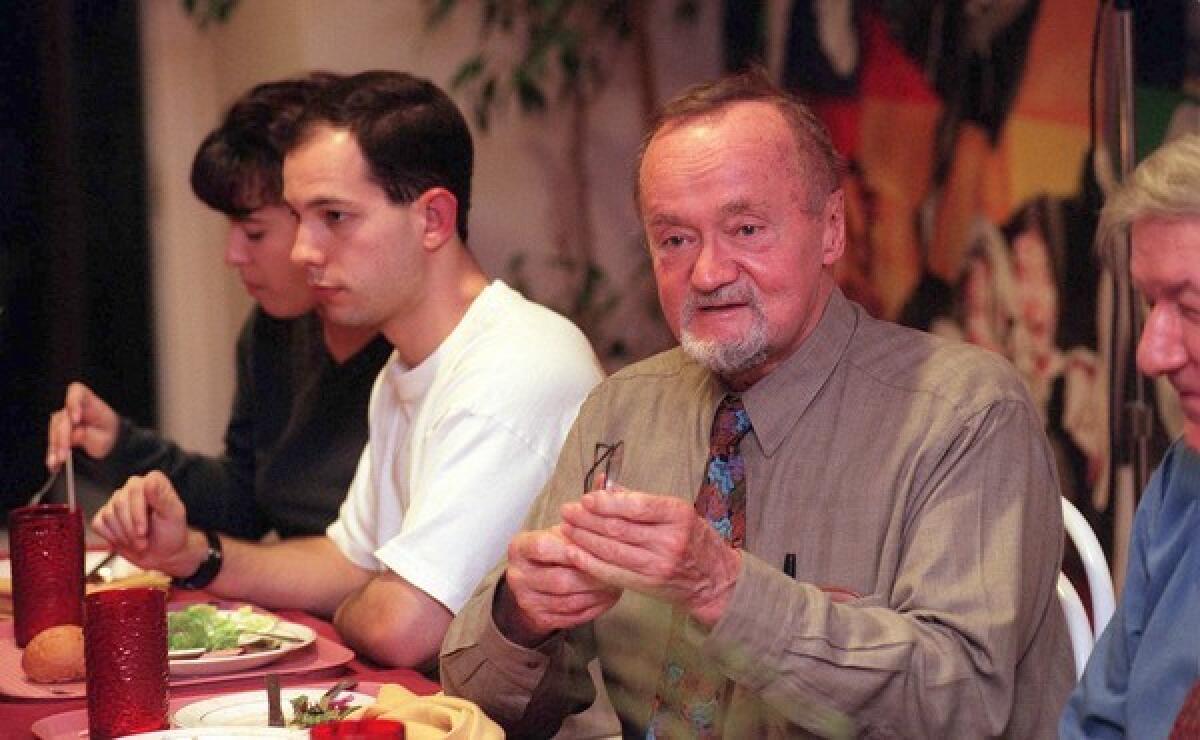

He and his wife, Donna, a lawyer and training director at the USC School of Social Work’s Center on Child Welfare, hosted students for regular Wednesday night dinners and turned their dorm apartment into a crash pad for stressed-out students during finals week, offering pizza, coffee and cookies until 2 a.m. He also hosted informal get-togethers where students met eminent writers and researchers, including evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould and authors Kurt Vonnegut and Studs Terkel.

At the same time, Toulmin was a highly regarded scholar, who in 1997 was chosen by the National Endowment for the Humanities to deliver the 26th annual Jefferson Lecture, the federal government’s highest honor for intellectual achievement in the humanities. He joined an esteemed group of previous lecturers such as psychologist Erik Erikson, poet Gwendolyn Brooks and historian Barbara Tuchman.

Born in London on March 25, 1922, Toulmin was trained in mathematics and physics at Cambridge University, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1942. During World War II, he was a junior scientific officer at the Malvern Radar Research and Development Station in England and later at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Germany. However, as he noted in a 1993 interview in the journal JAC, it quickly became clear to him that he was “not going to make a living as an experimenter” in radar because he often broke the equipment.

His true passion was the philosophy of science. After the war, he returned to Cambridge to earn his master’s and doctorate in moral sciences. He studied with Ludwig Wittgenstein, the famous Austrian-British logician with whom he shared a deep interest in physics.

In 1949, Toulmin began teaching the philosophy of science at Oxford University. Over the next five decades, he taught at a number of distinguished universities, including the University of Leeds, Michigan State University, the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. He joined the USC faculty in 1992.

He wrote, co-wrote or edited 20 books, including “The Philosophy of Science: An Introduction” (1953), “Wittgenstein’s Vienna” (1973, with Allan Janik), “Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity” (1990) and “Return to Reason” (2001).

His most important work, “The Uses of Argument,” outlined what he considered the six essential elements of any good argument: the claim; the data, or evidence; the warrant, or link between the claim and the data; the backing, or additional evidence; the qualifier, or strength of the claim; and the rebuttal, or exceptions to the claim.

The so-called Toulmin model of argumentation was ignored by most academics in philosophy but greatly influenced those in departments of rhetoric and communications, perhaps because it unfashionably rejected Aristotelian analysis as not very useful for everyday disputes. Toulmin’s method, according to a review in the Humanist, would “awaken philosophers out of a nightmare -- the nightmare brought on by an over-rich banquet upon logico-mathematical ideals.”

In addition to his wife and son, Toulmin is survived by children Polly, Matthew and Camilla; a sister, Rachel; and 13 grandchildren. A public memorial will be held at a later date. Memorial donations may be sent to Amnesty International, the Los Angeles Philharmonic or the USC Good Neighbors Campaign.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.