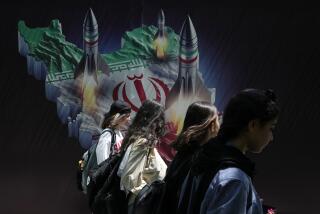

McManus: The nuclear countdown in Iran

Not long ago, an astute reader noted that it has been nearly two years since I wrote in a column that “most experts now estimate that Iran needs about 18 months to complete a nuclear device and a missile to carry it.”

His point — that those estimates were way off — was a good one, especially since experts are still estimating that Iran is 18 months away from being able to build a nuclear weapon.

So what gives? Why does Iran always seem to be about 18 months away from a nuclear bomb, at least in the eyes of U.S. officials?

For starters, estimates are only estimates. It’s hard to get a fix on the state of Iran’s research when Tehran refuses to allow full access for international inspectors to its military facilities.

The experts cite two other factors for why their forecasts were so far off. One is that Iran’s leaders seem not to have actually decided to build nuclear weapons; for the moment, they appear to prefer being a potential nuclear power to actually owning the weapons.

The other factor is sabotage. Those estimates of 18 months were based on what Iran could accomplish if all went well in its nuclear facilities. “But all never has gone well, and all will continue to not go well,” a U.S. official told me recently.

Israel’svice prime minister, Moshe Yaalon, put it more bluntly last week. “All sorts of things are happening” in Iran, he told Israel’s Army Radio. “Sometimes there are explosions. Sometimes there are worms there, [computer] viruses — all kinds of things like that.”

Neither the United States nor Israel admit that they are behind a sabotage campaign that has made Iran’s nuclear centrifuges unreliable, its computer software buggy and its precision steel defective. And the Obama administration has condemned the assassination plots, presumably the work of Israel, that have killed at least four Iranian nuclear scientists. But both Israeli and American officials predict that more sabotage is to come.

Oddly enough, all that sabotage may turn out to be the sturdy handmaiden of diplomacy — and an alternative to all-out war.

This month, Iran and six of the world’s major powers, including the United States, are scheduled to resume negotiations over Tehran’s nuclear program. The Obama administration hopes that the pressures of sabotage, military threats and economic sanctions — including a European embargo on Iranian oil that takes effect July 1 — will prompt Iran to accept fuller international inspections of its facilities and limits on its nuclear enrichment.

Obama and others have warned that this may be the last chance for diplomacy to avert military action.

And there is considerable sentiment against a war. Military officers in both the United States and Israel have warned that airstrikes against Iranian nuclear facilities, while they might delay Tehran’s ambitions, wouldn’t end the threat, and they could prompt Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to order a full-scale commitment to nuclear weapons.

Of course, negotiations aren’t likely to be a quick fix either.

An international agreement to stop Iran’s nuclear work, reduce its stocks of uranium and set up an international inspection regime would likely take years to negotiate. Iranians are deeply suspicious of U.S. intentions — and not without reason, since many American leaders have called for regime change in Tehran.

Meanwhile, Israel has insisted that it only has months to wait, not years — because it worries about Iran building enough defenses around its nuclear facilities to create what Defense Minister Ehud Barak calls a “zone of immunity” against attack.

What’s the alternative?

Once again, it’s likely to come back to sabotage — a middle option between all-out war and acceding to continued progress toward a nuclear Iran.

In a recent article, Michael O’Hanlon and Bruce Riedel of the Brookings Institution proposed relying on sabotage as part of a strategy they dub “constriction.”

“Essentially, we would continue to delay and minimize the scale of Iran’s nuclear program as we have been doing through sanctions and other means,” they wrote in the Washington Post. “We would keep doing this indefinitely, even if Iran gets a nuclear weapon.”

“There is little near-term prospect of reaching an agreement with Iran. But we can pursue the same goal with other means,” they argued. “Non-military methods have already slowed Iran’s nuclear program by two to three years.... That is every bit as much as we could hope to slow Iran with an airstrike campaign.”

The goal would be to find a way to freeze Iran’s nuclear work where it stands — which means that on Groundhog Day two years from now, I just might be writing another column to explain why Tehran is still, oh, about 18 months from a nuclear weapon.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.