Patt Morrison Asks: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar -- still hooked

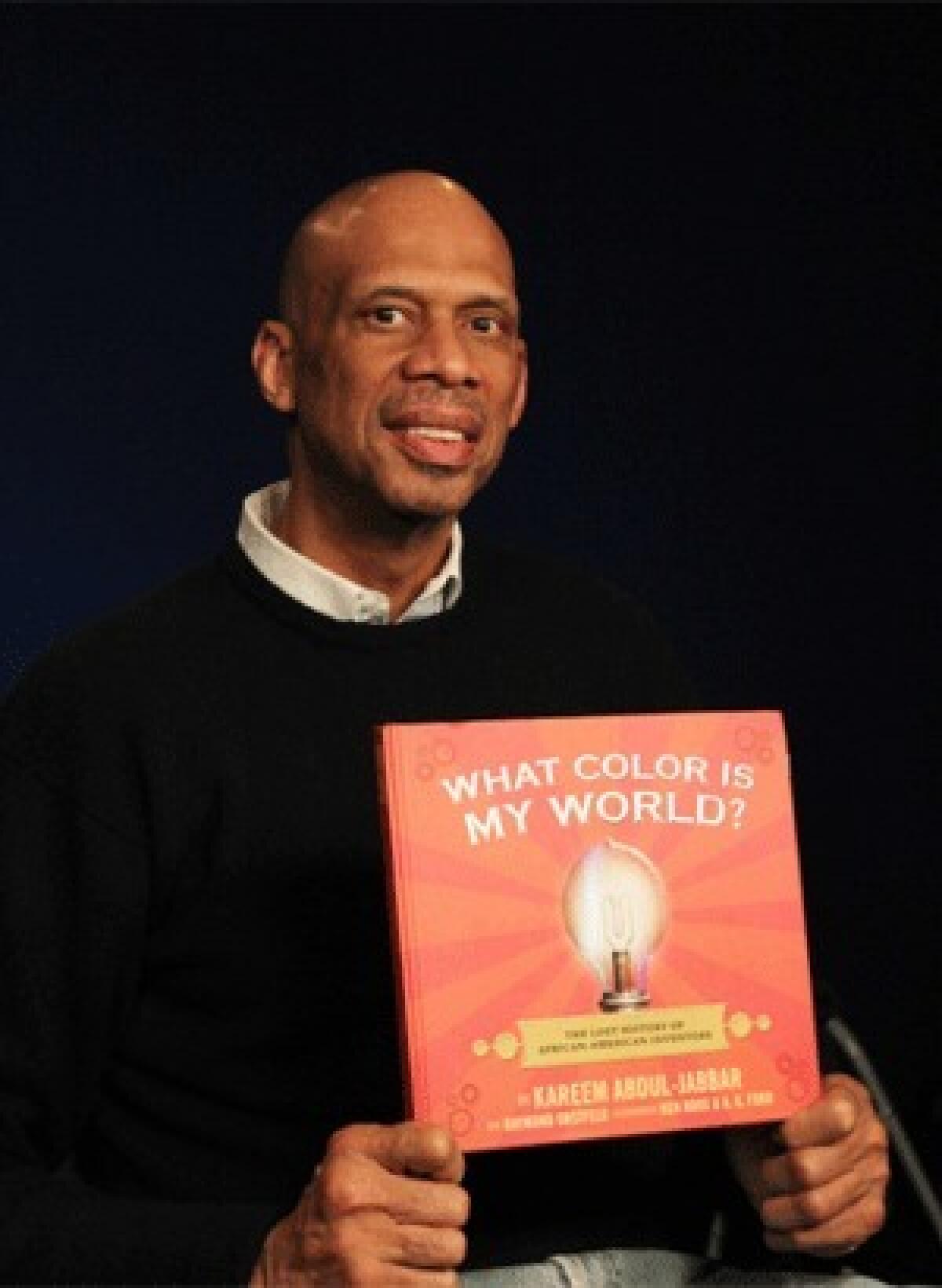

Only his number is retired — 33, in the Lakers’ purple and gold that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wore to glory on the basketball court. The rest of him is still working away, most recently on his latest book. At UCLA, in blue and gold, Abdul-Jabbar was a standout, an All American and player of the year — and a history major, which has served him well in his literary career. Some of his books have made it to the bestseller list, and this one, “What Color Is My World? The Lost History of African-American Inventors,” is a children’s volume with adult appeal. But in the midst of March Madness, he’s still watching the game he mastered, though two of his favorites are already out: Lehigh and Long Beach.

It’s March Madness, and almost every year there seems to be a Cinderella team from a plucky little school. We all love the story and cheer, but they never seem to win.

Sometimes they do! Loyola of Chicago, the 1963 champs, a small Catholic school. They beat the University of Cincinnati in the finals.

That’s the thing with basketball — you don’t have a huge program, [yet] you get a core of three or four guys who can play together and get a lot done. That’s the allure of basketball. People come from nowhere and do so well. It’s fun seeing those small schools beat the ones with [big] athletic programs. It’s the whole David and Goliath scenario.

I was really cheering for Long Beach State. I was hoping they’d pull it off. I was really sad, but I’m sure it’s great for their program.

Your book is about other kinds of heroes, African American intellectuals, inventors and creators.

I did a book in 1996, an overview of black history. In that process I became more aware of a lot of the black inventors of the 19th century. That put me on track to find this information, and it just expanded.

In a typical history book, black Americans are mentioned in the context of slavery or civil rights. There’s so much more to the story. People know George Washington Carver, period. He’s the only one anyone can think of.

Do you have a favorite among your subjects?

The one who stands out is Dr. Charles Drew [for whom the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles is named]. Blood typing and the establishment of the blood bank are so important. Millions of lives have been saved and the quality of life for tens of millions of people has been improved because of what we know now about blood types. Drew was right there at the foundation of it.

I was drawn to Percy Lavon Julian, who synthesized cortisone. When he graduated from college, his great-great grandmother finally showed him her scars from whippings when she was a slave.

And he had to go to Austria to get his doctorate because of bias. Cortisone — I’ve used that a few times!

When did you start learning about these men and women?

In high school. It was part of a federal mentoring program started by [professor] John Henrik Clarke. The challenge was to figure out how to make Harlem a better place. So they had a summer workshop where you got to do whatever felt special, so for me that was literature — writing. I was in the journalism workshop. We had to put out weekly newsletters, so I learned literally your job.

We’ll have to put you up for honorary membership in the L.A. Press Club.

I wrote about sports, and I was an editor. The summer of ’64 — that’s where I got the bug for knowing about black history. I had a good foundation in English, in grammar, in order to write about our community. That’s the first time I got an understanding of what my community was all about, and why it was so important to black Americans, because [New York City] was the place where people of talent could go and succeed.

Why is it so hard to communicate that history and get it to stick?

I think it’s the power of popular culture. If you talk to the average young kid and ask who he wants to be, he’ll tell you Kobe or Jay-Z. Sports and entertainment are the only places where inner-city kids see themselves being able to succeed. Their intellectual development is something they don’t relate to.

Not every kid is going to be Denzel Washington or Stevie Wonder. Not all of them can be Matt Kemp and play center field for the Dodgers. We’ve got to give them more avenues to succeed and do meaningful things. So the heroes in my book are mathematicians, scientists and engineers.

In that way I think I’m opening the door for these kids to get out of the little boxes they’re in with regards to what is possible. If we could get kids in the inner cities to spend the time in the library or in the lab that they do on the football field or on the basketball court, to put that effort and focus in these other directions, we’re going to have more people like Lewis Latimer [a patent expert who also who created a technique to make light bulb filaments], a black American who is at the foundation of electronics and telecommunications. And James West [developer of the modern microphone, in use today]. Black kids don’t know about this.

You wrote on ESPN.com recently about allegations of problems with UCLA basketball — immature players, fistfights, drugs, drinking. How has UCLA lost its way from the “Wooden Way,” Coach John Wooden’s program?

It was not my attempt to do a hatchet job. I’m sure Coach [Ben] Howland is doing the best job he can, and he’s a competent coach, so I’m not sitting on the sidelines throwing stones.

But Coach Wooden had a real, genuine interest in the people who played for him. His mentoring role was his primary objective — [that] the people who played for him get their degrees, learn how to become good parents and husbands and good citizens. And it colored the way [the team] interacted.

Nowadays kids get to a college program and it’s one and done; hey, adios. They don’t want to miss the big bucks [in the NBA]. The whole thing has changed.

Not enough “student” in student athlete?

It’s hard in this era.. In many instances [it] is just a quick showcase for some kid who’s going to sign a pro contract in 18 months.

Is it still possible to do it the Wooden way?

I don’t know. Letting the kids [go pro] so early has not been good for the pro game or the college game. [Those players] are immature and don’t understand the game at the level they need to, to immediately do well in the pro ranks. Maybe the age should be 20 or 21. That would be better for the kids. It would give the colleges a chance to have the kids stay longer and learn a few things and mature and all the good things college does for you. It’s not just about getting a degree. It’s the maturation process; it does a very meaningful thing for you.

Here’s Allen Iverson, about $150 million playing professional basketball — he’s [reportedly] broke now. What’s a player going to fall back on? His entourage? Where are they? Ray Williams, he played for the Knicks — he was living in his car. These people make hundreds of thousands, in many cases millions of dollars. And they can end up broke.

You went to UCLA perhaps as much because of Jackie Robinson as John Wooden.

He was my hero when I was a kid. I rooted for the Dodgers when they were in Brooklyn. I got a letter from him: Did I know he’d gone to UCLA? That was one of the incentives I had. [His letter] said it’d be a great place for me to go to school and get my education. I lost the letter in a fire in 1983.

What is going on with the Lakers?

I don’t know; I’m not close to it. I’m speculating just like you.

What about your book; what have you heard?

My older friends like it because the print is large and they can read it without their glasses! For me, it got to the point where my arms weren’t long enough to hold a newspaper far enough away.

No, not your arms!

My arms!

This interview was edited and excerpted from a longer taped transcript. Archive: latimes.com/pattasks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.