On thin ice in the Arctic

In the final presidential debate, when explaining why the Navy has fewer ships than in 1916, President Obama famously quipped that the United States also has “fewer horses and bayonets,” setting off a debate over quality versus quantity. In the Arctic — an increasingly important part of the world — the situation is simpler. When it comes to patrolling and securing the Arctic, the United States has neither quality nor quantity.

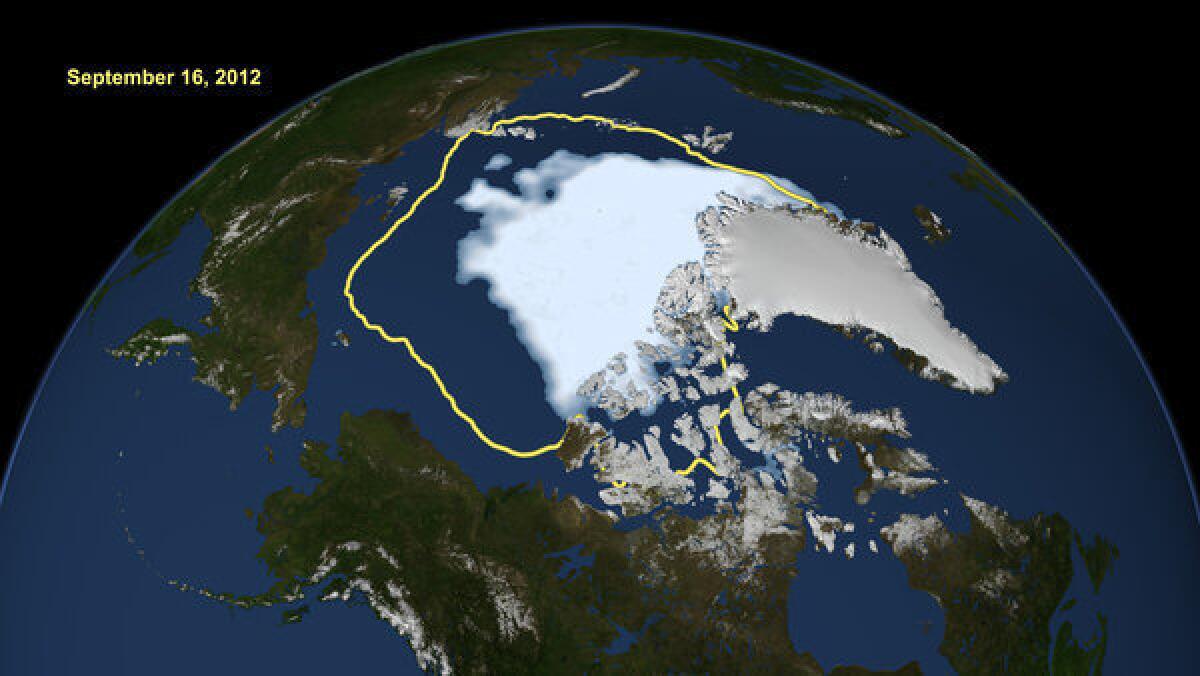

The rapid melting of the Arctic sea ice is opening up previously unnavigable areas to shipping and drilling. Many scientists predict that by 2030, the Arctic Ocean will experience ice-free conditions during the summer. The Northwest Passage — the once-mythical sea route between the Atlantic and the Pacific near the top of the world that explorers spent centuries searching for — is fast becoming a reality. Already, the maritime area in which the U.S. Coast Guard is responsible for safety, security and environmental protection missions is experiencing a significant increase in traffic.

To meet this challenge, the Coast Guard has three Arctic-capable icebreakers: two heavy-duty icebreakers — both of which were commissioned in the mid-1970s — and a more modern medium-duty icebreaker, the Healy. Were all three operational, the United States would lag behind several other Arctic nations in capabilities; in fact, only one — the Healy — is currently operational. According to a Coast Guard study, it will need at least six heavy-duty and four medium icebreakers just to meet mission requirements.

The Navy is not significantly better equipped. After its 2011 Fleet Arctic Operations War Game, the Navy concluded that it was not able to adequately perform long-term Arctic operations and would have to rely on support from the Coast Guard, among others, to bolster its capacity.

The 2013 fiscal year budget includes money to begin the acquisition of one icebreaker, but it remains unpassed. With the threat of automatic spending cuts in early 2013, known as sequestration — and other cuts to the defense budget likely even if the so-called fiscal cliff is averted — there seems to be little appetite in Washington to invest in new and upgraded Arctic-capable systems.

Thus, for all the talk of projecting power abroad and ensuring the freedom of the seas, we are unable to effectively patrol the waters off our own territory, and this in an area whose importance is growing at a rate perhaps second only to that of the Asia-Pacific region.

In the meantime, other Arctic nations are taking the initiative. Norway, Canada and Russia have made developing both their military and civilian capabilities in the Arctic a priority. Russia has 25 icebreakers, some nuclear-powered. Canada has initiated a modernization program of its navy and coast guard to include a new icebreaker and several new Arctic patrol ships.

The United States’ lack of investment in the Arctic is not limited to the military. Obama routinely speaks of investing in America’s infrastructure and rebuilding roads and rails. This is an admirable goal, but in most of north Alaska, there simply isn’t much infrastructure to rebuild. It must, instead, be built in the first place. As a result, development in the region has lagged behind that of the rest of Alaska and created an exaggerated tyranny of distance between towns. In the supermarket in Barrow, the northernmost city in the United States, for example, one can find orange juice on sale for the eye-watering price of $24 a gallon because of the costs of transporting basic goods.

Again, the United States would do well to look to other Arctic nations for inspiration. Norway, for example, has invested in new roads, and it is looking to improve existing infrastructure in its high north and to more effectively link the region to neighboring countries. The United States isn’t.

The manner and extent to which we develop the Arctic remains, admittedly, undecided and controversial, especially with regard to the extraction of its natural resources. Amid significant opposition from environmental groups, Shell Oil has begun drilling offshore wells in the Alaskan Arctic, though setbacks have delayed completion of the wells until the summer of 2013 at the earliest.

However, the development of our infrastructure and military, search-and-rescue and security capabilities in the region need not — and indeed should not — be reliant on any future decisions to increase drilling or mining. The reality is that the Arctic is increasingly busy. Cruise ships are already operating in the region; it is only a matter of time before freight and tanker shipping follows. It would be tragic if swaths of wilderness were polluted because a ship suffered an accident and the U.S. was forced to stand by idly and await help from another nation.

From the original purchase of Alaska being derided as “Seward’s Folly,” the United States has long had an ambivalent relationship with the Arctic. However, there probably will come a point when it will be forced to reckon with its role as an Arctic nation, whether or not we are prepared. We would do well to invest in our capabilities there now, lest we find ourselves reliant on little more than sled dogs and ice picks.

Seth Andre Myers is a research associate in the national security studies program of the Council on Foreign Relations.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.