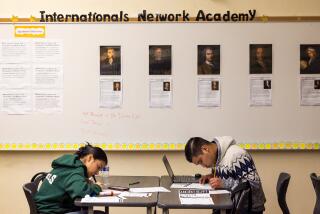

California’s future homeowners

Four years ago, USC demographer Dowell Myers predicted, in effect, that in the not-too-distant future Americans might be worrying less about too many illegal Mexican immigrants than about the education and training of those already here.

Who, Myers asked in his book, “Immigrants and Boomers: Forging a New Social Contract for the Future of America,” will fill the skilled jobs held by the millions of retiring baby boomers in the decades ahead? Who will be able to buy their homes?

Myers’ answer: For a large percentage of those retirees, their replacements will have to come from among immigrants and their children, the people who will compose the largest part of California’s working-age and home-buying population, and an increasing part of the U.S. population as well. At the same time, the sharp decline in the Mexican birthrate of the past generation will slow the growth of that country’s labor force and reduce the pressure to emigrate. In another decade or two, we may need more people of working and home-buying age than we’ve got.

Newly compiled census data on California homeownership, combined with recent economic and demographic reports from Mexico and the United States, confirm both points.

Begin with the housing factor. In a report released this month, Myers shows the dramatic generational and ethnic changes in California homeownership.

As the number of older, white homeowners continued to shrink from the 1980s through the first decade of this century — through relocation, entry into assisted living or rental housing, or death — most of their homes were bought not by younger whites but by Latinos.

In the 2000s, the total number of what the census calls non-Hispanic white homeowners in California declined by nearly 158,000. In the same decade, even as the percentage of all Californians owning their own homes went down, the number of Latino homeowners in the state increased by nearly 384,000, accounting for more than 78% of the growth in California’s homeownership.

As early as 2005, Myers wrote in “Immigrants and Boomers,” the most common surnames of new California home buyers were Garcia, Hernandez, Rodriguez, Lopez and Martinez. Nationwide, four of the top 10 names were Latino.

“It is young Latino home buyers, and also Asians, who have taken up the slack from diminished white demand,” Myers says in his new report. In the coming years, however, there’ll be even fewer whites to replace those old homeowners. “The clear challenge [then] will be how to pick up the growing slack…. ‘Who is going to buy your house?’ has become an important question for all of us.”

There’s a related question, crucial for both California and the nation: Who’ll have the job skills to replace those retiring boomers in the future?

While media attention has been focused on the Mexican drug wars and our own political battles over immigration, the big story may well be the growth of the Mexican economy and the increasing number of economic and educational opportunities it offers.

In the last four years the U.S. population of illegal immigrants declined from roughly 12 million to 11 million. Detentions of undocumented aliens by the Border Patrol are also sharply down. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, the number of illegal border-crossers who settled in the United States dropped from the annual average of 525,000 in the first years of this century to fewer than 100,000 last year.

Some of those changes are due to the economic troubles of the last four years; some may be due to tougher enforcement of immigration laws. But some may also be attributable to the declining Mexican birthrate and Mexico’s improving economy. The biggest issue of the next decade may not be closing the border to illegal aliens but opening opportunities, especially higher education, to immigrants and their children.

Yet as boomers retire by the millions beginning in this decade, taking their skills with them, California, rather than making college and other advanced education more accessible, is making access harder, shutting down programs and increasing the costs. “Cultivating a stronger base of future home buyers,” Myers says, “will help the older generation as much as the young. This partnership needs to be strengthened between older future home sellers and younger potential home buyers.”

So far, however, the critical economic and social nexus between the self-interest of older white homeowners and the younger Latinos and other immigrants who represent much of the state’s future is hardly perceived by much of California’s tax-averse electorate.

According to scholars such as Harvard economist Alberto Alesina, the greater the ethnic gap between voters and the perceived beneficiaries of public goods — education, social welfare and health programs and other services — the more reluctant voters are to support the taxes to pay for them.

The California of the 1950s and 1960s, which was overwhelmingly white and middle class, generously provided for those public goods. The California of the last three decades, in which immigrants and their children have become an increasingly large part of the population, has not. We are crippling our own economic future.

Peter Schrag’s latest book is “Not Fit for Our Society: Immigration and Nativism in America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.