For gay rights, a historic opportunity

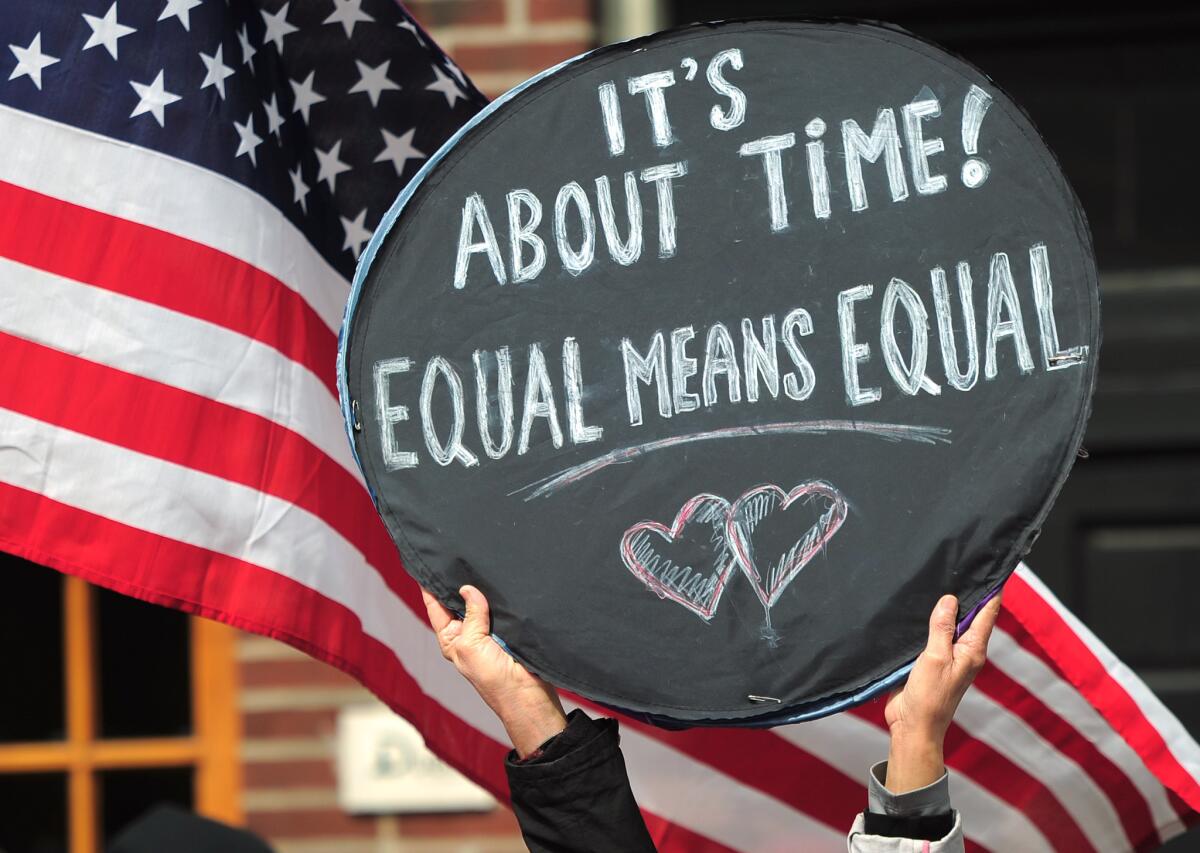

It’s hard to remember an initiative campaign that tore California in two as painfully as Proposition 8 did. The state might as well retire the number 8 when it comes to propositions; it will long be associated only with the 2008 measure that took the right to wed from gay and lesbian couples, on the same ballot that helped elect Barack Obama president.

Proposition 8, which shamefully wrote a ban on same-sex marriage into the state Constitution, was a backlash against the defining civil rights struggle of this era: the quest for equal rights for homosexuals. And because attitudes toward sexuality often reflect closely held religious beliefs, emotions ran high. On some California streets, neighbors found it hard to even be cordial toward each other if the lawn next door held a sign from the other camp — either the yellow-and-blue banner of Proposition 8 supporters, with its depiction of a traditional nuclear family(mom, dad, son and daughter); or the blue-and-green sign of the initiative’s opponents, who were fighting to protect a ruling by the state Supreme Court holding that gays had a right to marry.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments on whether Proposition 8 violates the U.S. Constitution. If the justices take the appropriately broad view of marriage rights, it will be a victory for same-sex couples not only in California but across the nation. A broad ruling in the Proposition 8 case would also determine the outcome of a second same-sex marriage case the court will hear Wednesday: a challenge to the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which defines marriage for federal purposes as “a legal union between one man and one woman.” For if a state may not deny equal protection of the law to same-sex couples, neither may the federal government.

TIMELINE: Gay marriage chronology

By a “broad ruling” we mean a finding that it is a violation of the Constitution’s due process and equal protection clauses for California — or any state — to deny same-same couples the right to enter a civil marriage, just as the court determined in 1967 that it was unconstitutional for states to prohibit interracial marriage. That was essentially the conclusion reached by U.S. District Judge Vaughn Walker in San Francisco after a trial in which supporters of Proposition 8 failed spectacularly to demonstrate that the initiative served a rational purpose.

It’s also the position being urged by David Boies and Theodore B. Olson, the bipartisan pair of prominent lawyers who are leading the challenge to Proposition 8 at the Supreme Court. In their brief, they eloquently emphasize that same-sex couples are seeking not some newfangled right but participation in a civil institution that benefits all committed couples. “Proponents view this case as a referendum on whether the institution of marriage should exist in the first place, focusing almost exclusively on why it makes sense for the states to grant heterosexuals the right to marry,” the brief says. “But this case is not about whether marriage should be abolished or diminished. Quite the contrary, plaintiffs agree with proponents that marriage is a unique, venerable and essential institution. They simply want to be a part of it — to experience all the benefits the court has described and the societal acceptance and approval that accompanies the status of being ‘married.’”

The justices could stop short of such a broad ruling while still restoring the right to marry to same-sex couples in California. One option would be endorsement of a narrow ruling by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which concluded that Proposition 8 violated the equal protection clause because it rescinded a right that gay and lesbian Californians had briefly enjoyed under the California Supreme Court decision. (That earlier decision, which was based on the state Constitution, was effectively repealed by Proposition 8.) A decision along the lines of the 9th Circuit opinion would also protect same-sex couples in nine states that have legalized gay marriage.

Another approach, suggested by a brief filed by the Obama administration and reminiscent of the California Supreme Court’s reasoning, would focus on the fact that gay and lesbian couples in California may enter into a domestic partnership — which, as the administration points out, is “distinct from marriage but identical to it in terms of the substantive rights and obligations under state law.” Given that fact, the administration argues, “Proposition 8, by depriving same-sex couples of the right to marry, denies them the ‘dignity, respect and stature’ accorded similarly situated opposite-sex couples under state law.”

Finally, the court could decide even at this late date that the supporters of Proposition 8 lack legal standing to challenge lower-court decisions nullifying the initiative.

Any of these outcomes would be preferable to an endorsement of Proposition 8 by the court, a result that would be a disastrous defeat for the cause of marriage equality. Still, we believe the justices should squarely address the issue of whether a state may deprive same-sex couples of the right to civil marriage. They could do that by concluding that there is no “rational basis” for that exclusion. Alternatively, they could accept the persuasive argument made by Boies and Olson and by the Obama administration that legal classifications discriminating against gays must be subjected to “heightened scrutiny” — meaning that Proposition 8 would have to be substantially related to an important governmental objective.

The arguments for the initiative offered by its supporters satisfy neither legal standard. In their brief, Proposition 8 proponents argue that it furthers the “critical societal function” of creating and nurturing the next generation and also is designed to prevent the evils of “unintended pregnancies outside of marriage.” But withholding the status of marriage from same-sex couples doesn’t interfere with the conception, birth or upbringing of children. Nor does the existence of same-sex marriage make heterosexual couples any less likely to marry before procreating. (The proponents’ brief seems to concede as much, declaring unconvincingly that the possibility that same-sex marriage might undermine traditional marriage “need not be shown in order to uphold Proposition 8.”)

The proponents make an additional argument, one that confronts the Supreme Court in every case in which it must decide whether to override the will of the people or their elected representatives. “Americans are engaged in an earnest and profound debate about the morality, legality and practicality of redefining marriage,” the proponents argue, “and this court should permit this debate to continue as it should in a democratic society.”

It’s true (and heartening) that advocates of same-sex marriage have made headway in the political process, most recently in elections last year in which voters in Maine, Maryland and Washington state approved marriage equality. But the Constitution applies in every state, and the Supreme Court must ensure that its protections are available everywhere. It is not impermissible judicial activism for the court, in construing the Constitution, to take note of new social realities. One such reality is the growing recognition that same-sex couples can and do form relationships as stable and committed as those of heterosexual couples.

Time is on the side of same-sex marriage, as public attitudes are rapidly changing. But the court’s responsibility is not to anticipate what the public might do. It is to decide what the Constitution commands. Sometimes, as the brief filed by Boies and Olson reminds the court, that means protecting minorities from “majoritarian prejudice and indifference.”

If the court does its duty, Proposition 8 will fall, and so will the Defense of Marriage Act. And California, where this story began, will be free of an ugly blemish on its deserved reputation as a progressive and tolerant state.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.