A California tuneup

In politics and government, California is a state divided, not so much between Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives, or business and labor as between political partisans and reformers. The partisans see politics as a struggle for power, and their goal is to acquire it, exercise it and protect it on behalf of policies they believe are fair and just. To reformers, power without rules is inherently corrupt. Their goal is to refine the rules of the game, believing that out of fairness and evenhanded enforcement will come policies that reflect the will of the people.

It was much the same here 100 years ago, when there was a widespread belief among progressive reformers that a majority of lawmakers in the Legislature had been bought and paid for by the Southern Pacific Railroad. By 1911, the company that 40 years earlier helped connect the East and West by laying tracks from Sacramento to Promontory Point, Utah, had become California’s political boss. Towns lived or died according to whether they paid off the railroad for a spur or an extension through town. Farms were at the mercy of the railroad’s freight rules and rates. Lawmakers checked in with the rail magnates before adopting or rejecting taxes on steamship companies and other competitors. A violent land dispute between the railroad and settlers became the basis of the 1901 Frank Norris novel “The Octopus: A Story of California.” The company and the politicians it controlled became known as “The Octopus.”

Railroad supporters scoffed at efforts to change the rules in the middle of the game. The rules, they argued, were fair: Get a majority on your side, get them to vote and you win. That’s politics. That’s democracy. But reformers said the rules were corrupt and made winning impossible for anyone but those who already held the reins of power.

To change the rules, and to break the lock that Southern Pacific had on the state, progressive Republicans in the 1910 election joined with organized labor to throw out the railroad’s business-oriented Republican cronies. Together with new Gov. Hiram Johnson, they proposed and campaigned for what have become the three faces of direct democracy: the recall, which allows voters to throw out an officeholder even before the next regularly scheduled election; the referendum, which empowers voters to overturn laws adopted by the Legislature; and the initiative, which lets voters circumvent the Legislature and adopt laws and constitutional amendments directly.

Contrary to popular belief, California was not the first state to adopt those Progressive-era reforms; South Dakota came first with the initiative and referendum in 1898, followed by Oregon, Montana, Oklahoma and others. California voters joined the club on Oct. 10, 1911, a century ago today. Happy anniversary.

In the last 100 years, we have used the recall once (in 2003, ousting Gov. Gray Davis), the referendum occasionally, and the initiative so often that it has become a regular feature of our even-numbered-year primaries and general elections, plus occasional special elections in between. These days, signatures for initiatives are gathered and ballot measures are put to voters by powerful public employee labor unions trying to tighten their grip on Sacramento, by private businesses trying to shape the market and state regulations to their advantage, by billionaires who sometimes seem to push policy measures as a kind of hobby, by would-be politicians who try out their campaign chops on pet measures and, occasionally, by grass-roots groups trying to shape law the way they believe it should be. Unlike The Octopus of old, the new octopus is a tangle of interests who use the initiative process for various ends. Joining together these arms is an initiative industry of consultants, pollsters, signature gatherers, lawyers and, of course, political parties. As is so often the case, reforms have been absorbed into the system they were meant to reform. Now the reform — direct democracy — has become the octopus.

So what should Californians do about it, 100 years later? There is little point in trying to eliminate direct democracy altogether; it is entrenched in a system that includes term limits, supermajority voting requirements in some local elections and a bevy of other peculiarities that Madison, Hamilton and the other founders never had in mind when they wrote the blueprints for a checked-and-balanced constitutional democracy in the 18th century. Besides, if the state government is going to make mistakes — and it has made some beauties — the people ought to be able to make their own. But a few nips and tucks may be enough to lessen the damage of our mistakes, or at least to quickly identify them and correct them.

Solving the problem begins with identifying it — and with distinguishing the actual disease from its mere symptoms. Is it a problem, for example, that the state Constitution is one of the longest in the world, and that it’s so easy to amend? Is it a problem that the initiative system has become the plaything of special interests if those interests are good for California, or if voters at least get to make the final decision? Does the initiative system lock out compromise, or does it foster too much compromise and lead to a perpetual stalemate? If initiatives give too much power to common people to make decisions based on too little information depending on their mood on election day, is the legislative system any better?

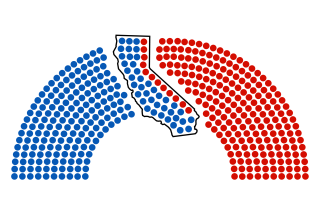

The Times has paid a great deal of attention to the structural problems of California and has supported many changes that are now on the books, including the elimination of the two-thirds vote requirement to adopt a budget, the “top two” candidate primary system and the law that takes redistricting power away from the Legislature and gives it to a citizens commission. Reform of direct democracy — whether it’s an overhaul or a simple tuneup — remained on our “to-do” list. Until now. In honor — or perhaps merely in observation — of the centennial of California’s signature reform, we today begin asking questions in earnest and, we hope, shaping some answers. Look for them here in the coming days and weeks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.