Music moguls seek security blanket

One way to judge the music industry’s troubles is to watch annual sales figures for CDs, which have slumped 25% since 2000. But it’s morerevealing to chart how the major record companies’ attitudes about new business models online have been shifting.

At first the shifts were almost too small to notice, as when thelabels started making a handful of downloadable songs available for $2.50 ormore. But as the file-sharing phenomenon grew and CD sales slipped, the changesbecame more pronounced. The labels started offering the rights to songs onterms that didn’t cripple their online partners. They embraced Apple’s iTunesMusic Store, whose anti-piracy technology doesn’t actually limit copying. Theycut deals with file-sharing companies for subscription services that let usersshare the songs they rented.

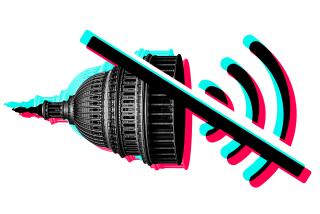

Along the way, though, the major labels adamantly refused to dothe kind of deal necessary to replicate what the original Napster, Kazaa andeDonkey had provided: they would not accept a flat fee a “blanket” license that lets Internet service providers sell an all-you-can-eatsonic buffet, enabling customers to download, burn and swap as much as they pleased.The rights would be included in the cost of a high-speed Internet access line,so the downloads would seem free while still generating royalties for artists,songwriters, labels and publishers.

That reticence may be giving way, too, thanks to therelentless decline in revenue. Just look at what the head of themajor record companies’ global trade group, let slip last month at amusic-industry gathering in France. If Internet service providers “want to cometo us and look for a blanket license for an amount per month,” IFPI chief John Kennedy said, “let’sengage in that discussion.”

His U.S. counterpart, Mitch Bainwol of the Recording IndustryAssn. of America (RIAA), quickly added that the licenses should be negotiatedvoluntarily, not compelled by the government. So that part of the labels’thinking hasn’t changed. Nevertheless, Kennedy’s remark reflects a potentialsea change in the way the record companies do business. If the labels followthrough, it could trigger the greatest explosion in innovation since engineersat the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany developed the MP3format.

That’s a big “if,” but two of the four majors have already takenthe first step. In England, a venture called PlayLouder MSP is negotiatingdeals with record companies and music publishers for a competitively pricedhigh-speed Internet access service that will include the right to downloadmillions of songs, transfer them to portable devices and share them withfriends. The main restriction is that subscribers can’t send songs to peoplewho aren’t customers of PlayLouder MSP. In other words, it’s a privateelectronic playground for music lovers.

That’s a big “if,” but two of the four majors have already takenthe first step. In England, a venture called PlayLouder MSP is negotiatingdeals with record companies and music publishers for a competitively pricedhigh-speed Internet access service that will include the right to downloadmillions of songs, transfer them to portable devices and share them withfriends. The main restriction is that subscribers can’t send songs to peoplewho aren’t customers of PlayLouder MSP. In other words, it’s a privateelectronic playground for music lovers.

The company, which expects to launch its service this year, plans to put a chunk of the monthly service chargesinto a royalty pool that would be divided according to popularitythe moreoften a song is downloaded, the larger the share of the pool that its copyrightholders will receive. To monitor the network and enforce its borders,PlayLouder MSP relies on technology that can identify songs as they passthrough the networkand, if necessary, block them. So far, several largeindependent labels from the U.S. and the U.K. have agreed to let the companyoffer MP3s of all their songs, while two of the majors, Sony BMG and EMI, haveagreed to supply songs wrapped in electronic locks. Those locks won’t make muchdifference, though; as part of the deal, subscribers will be free to share MP3sfrom all of PlayLouder MSP’s partners, including Sony BMG and EMI.

The shift in thinking is apparent even among labels who haven’tsigned on to the PlayLouder approach. In the past, label executives made threemain arguments against the blanket-licensing concept: it turned their companiesinto glorified marketing firms; it forced labels to fight over a fixed pool ofdollars, so that one artist’s gain was another one’s loss; and there wouldn’tbe enough money in the pool to replace all the CD sales that would be lost. Thefirst two complaints get little mention today; instead, the make-or-break issuefor blanket-licensing deals is the amount of royalties the service cangenerate.

That’s the right focus. Blanket licensing wouldn’t transformlabels into advertising companies; the only element of their business theywould lose is the part that distributes plastic discs, and that’s going awayanyway. When consumers can choose from a virtually unlimited supply of songs,the ability of a label to find, sign and promote the most compelling artistswill be even more important than it is today. And the fees that consumers payfor downloading rights represent only a portion of the money that PlayLoudercould generate for copyright holders. There’s also money to be made fromadvertisers, mobile phone companies, device makers and premium music servicesthat want to insert themselves into the network.

Developing a specialty broadband service for music fans is justone piece of the puzzle. Ultimately, more of the companies that feed andbenefit from the public’s hunger for digital music need to generate revenue forthe industry. In England, representatives of Internet companies, computer andconsumer-electronics manufacturers and the music industry are exploring thisissue as part of “value recognition strategy” working group. But it’s not clearthe group will come up with new market-based solutions, such as blanketlicenses. Instead, it may bog down in fights over how much Internet providersshould do to help identify and punish customers who share songs illegally.

In fact, some participants in the working group were surprised byKennedy’s conciliatory remarks because he’d recently stepped up the rhetoric against Internet providers that didn’t try to curbpiracy by their users. His organization has already sued more than 30,000individuals for allegedly engaging in music piracy online, while its U.S.-only counterpart, the RIAA, has sued more than18,000. The RIAA, too, has prodded Internet providers recently to do more tohelp its lawsuit campaign, although in a less menacing style than Kennedy. Butlawsuits are a holdover from 2003, when the music industry was an $11.8 billionbusiness in the United States. It was down to $11.2 billion in 2005, and album sales dropped an additional 5% last year. So far this year, the drop is even steeper. You have to wonder how low they have to gobefore blanket licenses look like a better approach than blanket lawsuits.

Jon Healey is a Times editorial board member and author of the Bit Player blog.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.