Can Spotify blaze a music trail in America?

The long-awaited arrival of Spotify, a popular European music service, in the U.S. last week marks an important milestone for the music industry. For the first time, the major record companies have embraced an online music service that lets people play the songs of their choice for free, in unlimited quantity (at least at first). There’s no monthly fee, no per-song charges. It’s not exactly a new era, and Spotify hasn’t unlocked the secret to making a profit off of online music giveaways. But it is another step forward for the entertainment industry as it adapts, slowly and fitfully, to the disruptive force of the Internet.

As a group, the major labels have been notoriously slow to support new business models online for fear of undermining music sales. That’s been particularly true for services that wanted to let people play songs on demand for free, which label executives feared would reduce CD and MP3 sales while also lowering the perceived value of music. Spotify’s basic, advertising-supported service allows users to play music on demand for free with no limits for six months, but only on a computer. After that, they can play 10 hours of music per month. To regain unlimited playback rights costs $5 a month; to be able to store and play songs on a smartphone costs twice as much.

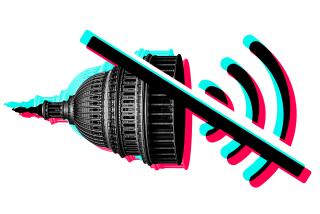

Wary about Spotify’s model, the major labels granted it licenses in 2008 only for Europe in exchange for a share of its revenue and an ownership stake. It quickly attracted more than 10 million users in seven countries, a little more than 15% of whom are paying customers. The labels wouldn’t let Spotify launch here, however, until it slashed the amount of music users could listen to for free.

Although Spotify’s growth has been impressive in Europe, it has yet to report a profit. It’s still struggling to collect enough from advertisers to cover the costs of the free service, including the royalties it has agreed to pay to labels and songwriters. (Some independent musicians have complained that the service pays them less than a penny per song played, but Spotify’s biggest competitor — over-the-air radio — pays no royalties to recording artists.) The way Spotify has made money so far has been by persuading people to upgrade to its paid services.

That’s no easy feat. Paid music services have languished in the U.S., in part because people still prefer to amass personal music collections (legally or otherwise) rather than paying to use an online library. Besides, consumers can find millions of songs for free as music videos on YouTube and Vevo, which sustain their businesses by commanding higher advertising rates than Spotify can.

Nevertheless, as Spotify demonstrates, the alternatives to 99-cent downloads and illegal file-sharing are expanding. Spotify may not succeed, but at least it gets a chance to blaze the trail.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.