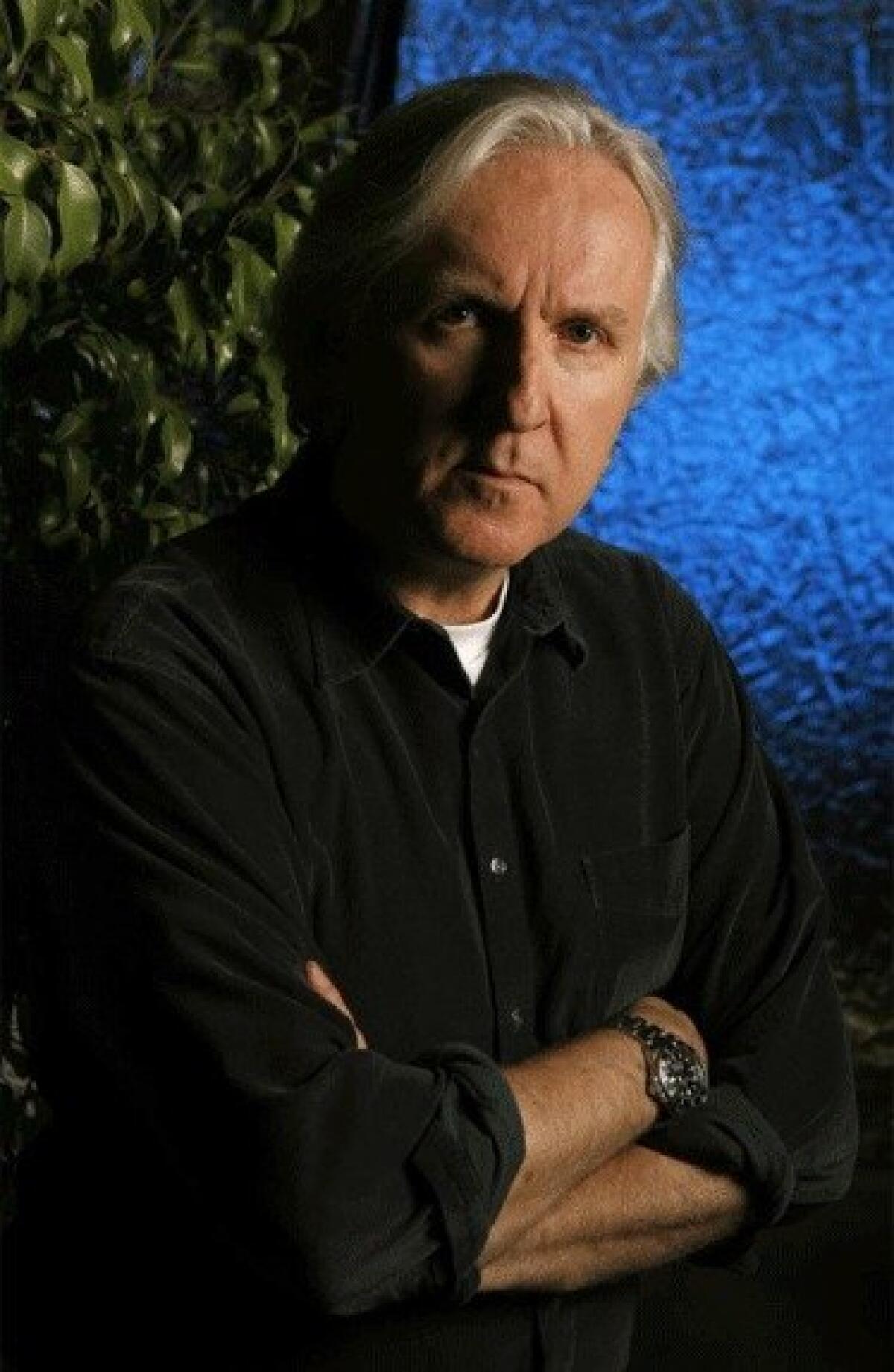

Patt Morrison Asks: James Cameron, a man overboard

The Challenger Deep, a fissure in the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean, lies farther below the Earth’s surface than Mt. Everest reaches above it. And James Cameron, the science-enthralled director and underwater explorer, made it his Lindbergh moment, soloing humankind’s deepest-ever plunge last month in a purpose-made submarine fitted out — natch — with 3D cameras. One hundred years ago today, the world’s most famous accidental deep dive took the ocean liner Titanic to the bottom of the Atlantic. Cameron made that story into the film “Titanic.” I spoke with him just before his epic descent, and asked him to ruminate on the ship that disappeared in 1912 and his own disappearing act into the ocean depths. You know what they say — whatever floats your boat.

It was diving that brought you first to the subject of the Titanic and then to Titanic itself. What did you think a film could add to something so well documented?

I wanted to graft my fictional element into the tapestry. Part of it was to evoke that time with its rigid class distinctions and what that meant symbolically, this distinction between haves and have nots. That’s obviously a big topic of conversation in this political season with the 1%.

The event was refracted in the media of its time quite differently — [as] heroic first-class people who stepped back and allowed the ladies onto the lifeboats, ignoring the carnage among the crew members and third-class [passengers] who were left to fend for themselves.

I don’t think [it] was a particularly innocent age. It may have appeared that way, but the forces that would take us into highly technological warfare [in World War I], with machine guns and mustard gas and tanks, were already at work.

Being a kid of the ‘60s, I had a jaundiced view of history. I wanted to read between the lines. I wanted to look at the corporate whitewash. I wanted to see where people may have had reason to dissemble a little bit.

You go through the [Titanic inquiry] testimony, and for me it was the Pentagon Papers. I got a sense that history is a bit of a consensus hallucination. Our view of it is warped by those who spoke the loudest and with the most power to impress. People trusted authority. They didn’t look any deeper. Today we sort of tear it all apart and question everything.

I once was assigned to interview Titanic survivors, and I was moved to be sitting at one degree of separation from it all.

When you touch the hem of history like that, it all takes on a greater meaning. [It] had the same effect when I dove the wreck. Seeing the remains of the decking, right where the band would have stood and played — we thought: This is the place.

You feel that same thing when you’re at Gettysburg or wherever there’s been some great disruptive event; you feel almost like there are these aftershocks that rebound through time.

But didn’t Robert Ballard’s finding the wreck in 1985 diminish its significance? When you bring myths into the light, they seem smaller.

I think that happens, but I don’t think it’s happened with Titanic. The wreck is so mysterious and majestic and in such a remote place. If we dragged it onto the beach into the sunlight, it’d be very different. It’d just be this sad old rusted hulk. In situ, it’s like this great haunted mansion. For me, [Ballard’s] finding the wreck was the inspiration for wanting to do the film. Wrecks are on the bottom of the ocean for a reason, and the reason is usually something very bad.

Titanic was the ultimate novel-like story, the classic sense of hubristic folly, that we’re too big to fail — and where have we heard that before? Then all of a sudden it comes a cropper and everybody looks around, like, I can’t believe that just happened, when in fact it was almost inevitable.

“Titanic” is back in theaters. But will people bother to go, when they can watch on a device in their pockets?

3D is a great reason to bring the film to theaters. [But] there’s a sense that appointment entertainment is getting extremely eroded. People [make] a little contract with themselves: “This is a film that I want to see on the big screen where I won’t be interrupted, I won’t be on my cellphone, I won’t be putting it on pause, I won’t be doing my homework.” It’s very different from watching it on video.

Or on a screen the size of a Post-it note.

I don’t like to think I’m making movies for iPhones! God bless people if they want to follow a bit of the story, if it’s helping keep the movie industry alive and vigorous. But I still believe in that sacred experience of the big dark room with a bunch of strangers where you check the dipstick on your humanity.

You’ve done countless dives since you first explored the Titanic. What have they taught you that you’ll use diving the Mariana Trench?

Each one was more ambitious than the last, and each had different hurdles and setbacks each time. It teaches you to be a little bit resilient and a little bit patient. I used to get quite hyper when things would go awry, and now I know that it’s sort of normal. You stay calm and keep everybody on track because people who are new to the game, like some of our young engineers who have never accompanied their hardware into the ocean before, get a little freaked out when things don’t work. I have to remind them that the ocean is going to eat your gear, and you’ve got to get it back and patch it together and learn from your mistakes.

I hear that you get seasick. Are you going to wear an anti-nausea patch?

I used to, but they kind of turned and bit me 12, 15 years ago. I got turned on by astronauts to what they take to prevent space sickness. When it gets rough, I’ll be lying down. I don’t profess to have a cast-iron stomach. I think of that as the measure of how much I love doing this.

You’ll be alone, at depths and in an environment where virtually no one has been before.

It’s pretty cool, the idea of solo. I’ve dived in three-person subs, two-person subs, now this one-person vehicle. It’s less emotional than the fact that the task-loading is higher. Typically one of the pilots would be operating the sub and I’d be operating the camera, mov[ing] lighting booms. Now I’ve got to fly the vehicle as well. [It’s] pretty busy in that little cramped cabin.

Like being in the Mercury Project space capsule, in the early days of manned spaceflight.

It’s very similar. The good news [in a solo dive] is you don’t have to worry if the other guy had too many beans for lunch!

This interview was edited and excerpted from a longer taped transcript. An archive of Morrison’s interviews is at latimes.com/pattasks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.