The correct Hillary Clinton stereotype

On the afternoon of the New Hampshire primary, I had a political epiphany of sorts while standing in line at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco waiting for a prescription to be filled. In front of me, a middle-aged woman in a sensible pantsuit was soothing her rattled, elderly mother. “It’s OK, Mom, they made us go to the end of the line because I didn’t wait until your name was on the board, but you don’t need to stand. Sit down and relax, and I’ll handle it.”

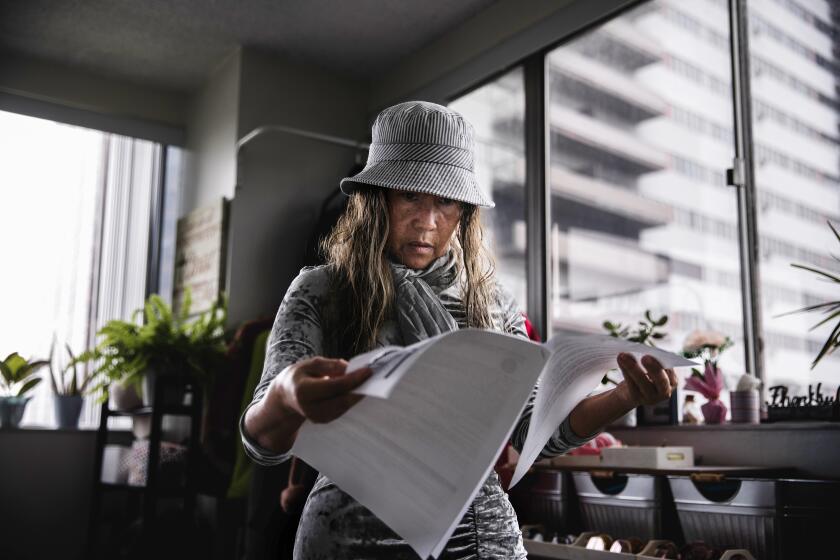

In the row of chairs to my left, another woman in business wear -- she’d clearly just run in from the office -- was applying similar verbal balm to her fretting parent. “That’s not a problem. I’ll call the doctor and make sure he understands that, and then I’ll move that other appointment to tomorrow morning. Don’t worry.” A pitched cellphone battle with the doctor’s recalcitrant gatekeeper followed. Evidently, the daughter won. “It’s fixed,” she told her mother. “I’ve taken care of everything.”

Listening to these women manage their mothers with effectiveness and as much patience as they could muster, admitting to errors, standing in interminable lines, speed-dialing medical professionals, I wanted to ask, “Could you run my country?”

As it happens, I’m not alone in wishing for a nation run by someone whose desire for our well-being is passionate but whose actions on our behalf also exude bedrock competence, someone who lacks any flash whatsoever except the flash that keeps a person assiduously doing the hardest things in life. In New Hampshire and all across the country, many female voters seem to be thinking along the same lines.

The media, punditry and pollsters have been viewing this historic female candidacy, and the candidate herself, through the Madonna-Medea prism they’ve applied since at least the Victorian era to women who venture into American public life. In so doing, they have ignored a whole other model of womanhood that is central to female experience. If they are determined to think of Hillary Clinton in stereotypical female terms, at least they should get the stereotype right.

That ignorance was on prominent display after New Hampshire, as analysts groped to explain the primary results and came up with explanations that were as offensive as they were phantasmagorial. One theory, admittedly far-fetched but avidly promulgated, held that Clinton’s unexpected surge of support came from lower-class voters who were secretly (that is, un-poll-ably) racist. Some pundits acknowledged that there might be a gender dynamic at work but allowed for only one possibility: Female voters were easily manipulated saps who’d let a few girl tears muddle their political sense. Pundits debated whether Clinton’s tears were “real” or “manufactured” -- that is, whether she was some weak sob sister who couldn’t hack the rough-and-tumble of a man’s world, or just a power-grabbing witch who would do anything to hang on to her broomstick.

A few, such as San Francisco Chronicle reporter Carla Marinucci, offered more cogent appraisals. She pointed out that female voters didn’t seem to be responding to Clinton’s tears so much as to their outrage at men’s reactions to those tears (in particular, men in the media).

Clintonhas not based her campaign, or much of her appeal, on her femininity or her womanhood. However, the public (and especially the media) persist in viewing her through that lens. The problem is that it is a distorted lens. It only sees half of female experience. Clinton, and virtually all of the female politicians who have come before her, wind up being assessed according to a long-standing division, then condemned either way: too tenderhearted or coddling (the criticism implicit in “Hillarycare” or “nanny state,” as well as in the initial reaction to her tearing up in New Hampshire) or too unemotional and controlling (implicit in “Hillary’s not personal enough”). In either case, the candidate is being judged not just as a woman but as a mom.

American society characterizes women as caregivers based on their young years as mothers. And when the American media demand emotion and warmth from Clinton, they are voicing the demand of a child to its mother (a demand not made equally to its father).

But there’s an entirely separate realm of female caretaking that is, in fact, more relevant to national leadership and to Clinton’s candidacy. Daughters shoulder the overwhelming burden of the care of our elderly parents. This too is a sphere of women’s experience, far more familiar to the women in the middle-to-older age bracket who supported Clinton most fervently, but its precepts are very different.

The woman caring for her aging parent isn’t being asked to bolster a juvenile ego with the necessary dollops of cooing, mirroring and inspirational atta-boys. The availability that a child asks from a young mother is not the quality most required in a middle-aged woman caring for a mature parent -- or a mature nation. Competence is. If that competence is backed by the humanizing force of tears, that is lovely and appreciated. But as those women at Kaiser knew, the moment called most of all for practical solutions and a reliable problem-solver.

The greatest show of nurturance those women could possibly evince was steeling themselves to stand in that line all over again and make that hectoring phone call to yet another doctor, even if they were perceived as a “bitch” by the receptionist on the other end.

In their appraisals of Hillary Clinton, the pollsters and pundits who have not gotten beyond that mommy/ball-buster teeter-totter narrative of American womanhood also have not begun to diagnose gender dynamics beyond the perspective of the little boy and his mom. A lot of female voters, however, may be factoring in a whole other kind of female archetype, whose wet eyes do not signal weakness and whose flashes of anger do not signal coldness, only pragmatic perseverance.

If pundits ever tried to understand what some female voters know about the complexity of women’s lives, they might begin to comprehend the appeal of a female candidate whose ethic of caring and whose posture of femininity derive from responsibilities beyond the maternal. And then they might begin to understand the affection of women in New Hampshire who put her over the top.

Susan Faludi is the author of “The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post 9/11 America,” a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.