Stopping California’s next meltdown

Today’s topic: The failure of the propositions didn’t eliminate the need for budget reform. What are the right steps for California to take to prevent the next fiscal meltdown? Daniel J.B. Mitchell and Tom Campbell finish their discussion on the state budget crisis.

Give the governor real budgeting power

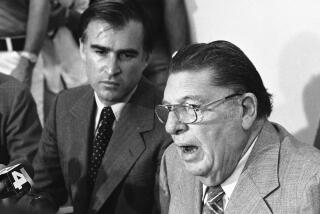

Point: Daniel J.B. Mitchell

Tom,

Our question today asks us to consider the next budget crisis, not the current one. There are calls in the wake of the present crisis for another round of initiative reforms or even a constitutional convention.

I have to admit a bias. I was raised in New York City, and when I looked across the East River, I saw the Brooklyn Bridge. The Brooklyn Bridge was completed in the 1880s, hardly a time of good government in the city or state of New York. “Boss” Tweed of Tammany Hall went to prison in part because of corruption related to the bridge, but at least they did get it built. In contrast, California, with all its do-good reforms and direct democracy, can’t accomplish the basics. So I am skeptical that the proposals currently on the table would avert the next budget crisis.

What I do know about California is that voters look to the governor when they want a problem fixed. We elect many state officials in California, but most voters don’t know the difference between the controller and the treasurer. Voters have effectively neutered the Legislature through a series of initiatives going back to the late 1970s. In contrast, they see the governor as California’s CEO.

Thus, when we had the budget crisis under Gov. Gray Davis, voters replaced him with Arnold Schwarzenegger, who promised to fix the problems. Through their actions (though they may not say so), voters seem to want a weak Legislature and a strong governor. The problem is that an ineffective Legislature is a severe handicap for a governor who wants to exercise leadership. In the end, there is no budget without the Legislature.

So here is my proposed reform to avert the next budget crisis. Henceforth, if the Legislature has not enacted a budget by July 1 of any fiscal year, the governor’s May revise is the budget until some other plan is enacted. My reform would end the situation in which the state has no budget in place and bills can’t be paid, even when there is money to do so. More important, if you look at recent governors, all were centrists who believed in fiscal prudence, whatever their spending priorities were. If Davis had operated under my reform, he wouldn’t have allowed the tax windfall from the dot-com era to be spent. He would not have allowed the Legislature to spend so much during the recession of the early 2000s, causing the state to run out of cash.

If the reform had been in place under Schwarzenegger, we would have built up a rainy-day fund without any need to pass the defeated Proposition 1A. And we would have adjusted to reduced revenues as other states have. Voters expect the governor to manage the budget. The next governor needs the tools to do so if we are to avert future budget crises. And what if voters don’t like the next governor’s budgets? There is always the option to recall or to not reelect. What do you think, Tom?

Daniel J.B. Mitchell is professor emeritus at UCLA’s Anderson Graduate School of Management and School of Public Affairs.

Making the ups and downs more predictable

Counterpoint: Tom Campbell

Dan,

I have enjoyed our exchanges and appreciate your knowledge and insight, but I can’t agree with the idea you present today. The California budget should not be decided by one person. In the May revise, the governor could propose a tax increase; as I understand your suggestion, if the Legislature stalemates, we could actually increase taxes on Californians on the say-so of one person. And even without an increase, if revenue is rising naturally, a liberal governor could spend it all and lock that spending increase into state spending formulas for years to come.

I have an alternative. When we don’t have a budget on time and revenue is rising from the previous year, we should extend the previous year’s budget. After all, the previous year’s budget is the most recent expression of the will of the people’s representatives. This approach would provide a useful check against what has happened so often in our state: Temporary revenue increases get locked into permanent formulas for increased spending well into the future. When revenue is falling and the Legislature fails to pass a budget on time, we ought to use the previous year’s budget, with all categories of spending cut across the board until the Legislature passes a new, balanced budget. Of course, some categories can’t be cut because of the U.S. Constitution (payments on state bonds, for instance), but these categories are few. If we have a rainy-day fund, funds could be used to augment the spending levels up to the amount of the previous year’s totals. I drafted this proposal in 2005 for the Legislature’s consideration when I was the state’s finance director, but the Democratic leadership did not even allow it to come to a vote.

We need to go even further. In any given year, we should not spend more than we did the previous year, adjusted for inflation and population growth. We used to have this rule in California, from 1979 to 1990. It was adopted by initiative with the support of then-Democratic Assembly Speaker Leo McCarthy and Assembly Republican leader Carol Hallett. There would be exceptions only for projects that had their own funding source (such as bonds paid for by toll-road fees) and natural disasters.

We need to build up a strong rainy-day fund as well. Over the course of 10 years, we should gradually save enough from every year’s budget so that, at the end of that period, we could actually budget based on the amount of taxes received in the previous year. Put the taxes Californians pay to the state in an interest-bearing account for one year; don’t spend the money until next year. That way, everyone in the Legislature would know exactly how much money we had to spend. Democrats and Republicans could disagree in good faith about where to spend, but not on how much money is available. And were revenue to fall, as it is now, we’d see it a year in advance and begin to take the steps needed for the next year.

All these changes and the one you suggested, Dan, would require a constitutional amendment. At least while a fiscally responsible governor is in office, however, we have another approach that doesn’t require a constitutional amendment: The governor can use the line-item veto to cut spending down to achieve a real balanced budget.

Tom Campbell is a former U.S. representative, state senator, state finance director and dean of UC Berkeley’s business school. He has formed an exploratory committee to run for governor.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.