Downtown’s bipolar housing policy

I’D LIKE TO TELL YOU what local politicians mean when they talk about “affordable housing,” but I can’t. It’s not because I don’t understand the concept of affordable housing; it’s because our civic leaders love to talk about “affordable housing” for the few while embracing policies that render housing unaffordable for the many.

It doesn’t help that the phrase “affordable housing” is mutable to dozens of different situations. It might refer to creating lofts for first-time buyers, to subsidizing homes for the working class, to a bond or trust for building low-income housing, to housing government employees in pricey areas, or to keeping single-room occupancy hotels (SROs) open for people who subsist at the economic fringe.

The current leading indicator of how abstruse the term can be is Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s proposed $1-billion affordable-housing bond, scheduled for the November ballot. If you think the bond will buy a specific type of affordable housing, think again. In truth, it’s a catch-all for nearly every kind of residential development on the south end of the marketplace. In the words of Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce President Gary Toebben, some of the money “will be used to fight homelessness, but much of the funding, however, will help young professionals, police officers, teachers, firefighters and nurses realize the currently unattainable dream of homeownership.” Even transit-adjacent housing merits a mention.

Common-sense economics warrants that the best way to make something “affordable” is to create a bigger supply of it. But city officials historically have taken actions to limit affordable housing, rather than to err on the supply side. The city routinely regulates private property rights, to build more schools, more big-box stores; now, it will even regulate transient hotels, pleading “affordable housing,” to make sure that our most indigent citizens are beholden to agency and litigation rather than to elementary supply and demand.

This is what’s happening to SROs downtown. In May, the City Council passed what was called a one-year “moratorium” on owners converting SRO hotel units into pricier, tonier cribs. This action spawned still more guidelines, by L.A.’s Community Redevelopment Agency, which called for a 55-year commitment by transient hotels to offer “affordable housing” units (apparently, the agency considers it better not to redevelop than to redevelop).

But even there, the mutability of affordable-housing language contains contradictory messages. The CRA’s guidelines are actually meaningless from hotel to hotel, even from floor to floor, because SRO hotels can, with the right kind of hall monitor, demonstrate that some of their floors aren’t transient at all. In fact, some floors in these buildings are cushily affordable enough that a handful of CRA employees can (and do) reside in them. And the one-year moratorium doesn’t seem to apply to at least one hotel, the Cecil.

Converting downtown SRO units to more upscale condos or lofts would mean bringing more units onto the market, which could make housing more “affordable” -- for the middle class, that is. And reducing restrictions on low-income landlords would encourage more of them to build in the first place. But the city’s SRO ordinance and the CRA guidelines run away from this in the interest of perpetuating a different and more malignant housing policy: containment.

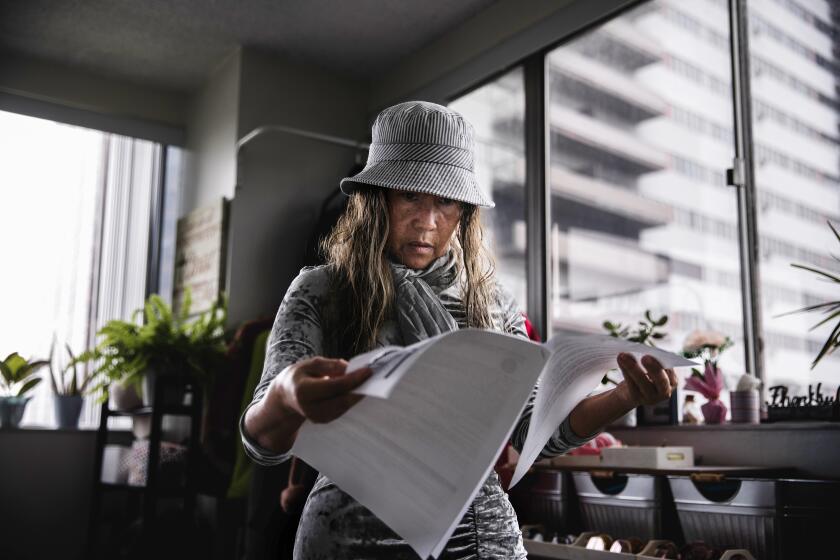

Since 1970, containment has roped off L.A.’s skid row within a certain designated area downtown, once again in the name of affordable housing. A 2004 update to the state’s notorious Ellis Act of 1986 is the latest enabler. Although the original act gave apartment owners more leeway in evicting tenants if they wished to get out of the landlord business, the amendment gave big cities leeway to decide whether their SROs should be exempt. Locally, social service organizations pushed hard to maintain the SROs in the skid row containment zone. “Skid row is an endangered, low-income community that has to be preserved,” The Rev. Alice Callaghan, the director of Las Familias del Pueblo, recently told CityBeat. To Callaghan, redevelopment in the containment zone eliminates too much “last resort” affordable housing. Other cities have coped with this elimination by linking the construction of new “last resort” housing to the redevelopment of old sites.

The old policies and laws, of course, were not written in a housing market quite as stratospheric as today’s. When one sector of a city is fenced off not just for the sake of preserving below-market units, but to insulate the whole zone from natural market forces as well, whether or not we can reasonably call this fencing-off a “policy” anymore remains a question. It is more like an “anti-policy”; like cordoning off a crime scene for the sake of perpetuating a crime, rather than solving it.

The policy of containment thereby makes for ordinances and actions that have no single policy objective at all; thus, ordinances affecting downtown perpetually come down on no particular side, while always making for more exceptions than rules.

Since the boom in adaptive reuse housing downtown -- a boom facilitated by City Council actions in 2002 -- an enormous amount of work has been done in the name of skirting the issue of containment even while answering to it, which ends up making housing policy for downtown Los Angeles schizophrenic in nearly every instance.

So the city will make a truly grand avenue of Grand Avenue for perpetuity, while passing an ordinance ensuring that, half a mile east, blight will remain blight for at least two generations.

The city attorney will issue findings that, absent court decisions backing them, don’t even find their way to potential enforcers. The Department of Building and Safety will regularly ignore the findings of other agencies and later plead ignorance. The Community Redevelopment Agency will study the problem and issue grandiose but arbitrarily enforceable, floor-by-floor edicts. And City Council members will talk of “affordable housing” for the few, even while supporting policies (such as the SRO-conversion moratorium) that effectuate artificial middle-class housing shortages and thereby render housing unaffordable for the many.

Development is an utterly exhausting process involving hard hats and even harder heads. But to best help the displaced, hardscrabble and at-risk tenants of downtown SROs -- as well as those who are not yet homeowners but who would like to be -- downtown stakeholders would do well to acknowledge that maintaining the policy of containment in the middle of a housing renaissance makes for bipolar housing policy.

The next step toward redress will not be an ordinance or a bond, but mustering the political courage to admit that to bring about real “affordable housing” solutions for everyone involved, the overriding policy of containment must be brought to an end, once and for all.