Beware of Sacramento’s crash tax

Travel tip: if you’re thinking about driving to Sacramento, don’t. Cancel the hotel reservation. Skip the big convention.

If you’re merely planning to drive through, don’t linger. Better yet, chart a scenic detour that avoids the city.

If you’re flying here, don’t rent a car after landing. Call a cab or take a shuttle.

Our state capital is about to become inhospitable to out-of-town motorists.

Sacramento — River City, The City of Trees, Sacotomato — is the latest local entity in California to adopt the dreaded “crash tax.” More than 50 have imposed it as they struggle to make ends meet.

Starting in another 10 days or so, an out-of-towner who has the misfortune to get into an accident that prompts the dispatch of Sacramento city firefighters or paramedics will be billed for the service if the visitor is judged to be at fault. Insurance companies will decide who’s liable in a multi-car accident based on the accident report.

But right off, this smells of potential hometown favoritism. The odds seem stacked against the out-of-towner. If the city can pick up extra bucks by blaming a non-resident, it’s human nature — and government nature — that it would.

An insurance company might pay. But if it didn’t, the motorist would be stuck.

“Typically, an auto policy doesn’t cover the cost of a fire department response to an accident,” says Sam Sorich, president of the Assn. of California Insurance Companies.

And even if the insurance company does fork out, if the crash tax scheme continues to catch fire, it’s a good bet auto premiums will be rising in California. “Insurance companies will have to account for the [payouts] in the rates they charge,” Sorich warns.

He adds, referring to the capital community: “We’re supposed to be welcoming people to come and talk to their legislators and see how their government works. But now we’re saying, ‘We may charge you.’ ”

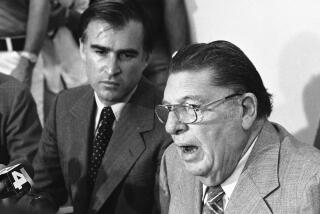

“Double taxation,” asserts state Sen. Tony Strickland (R-Moorpark), who has introduced legislation to outlaw crash taxes.

Strickland notes that out-of-towners already pay local sales taxes — in restaurants, stores and auto dealerships. That should suffice, he asserts.

The conservative lawmaker also makes another point: Many motorists might just leave the accident scene rather than stick around and risk getting hit by the crash tax.

It hasn’t been determined whether Strickland’s bill would outlaw only future enactments of the tax — which technically is a fee — or also void all current ordinances. That will depend on potential bill amendments and legal interpretations.

At least 10 states restrict local governments’ ability to charge so-called accident response fees. The fees are a relatively new trend in government revenue-raising and vary from entity to entity.

In California, the vast majority of crash-taxing governments sock only non-residents, although a handful also hit local motorists who are at fault. Sacramento will exempt owners of local businesses.

The actual billing is contracted out to private operators, who grab a cut of the take. So they tend to be aggressive bill collectors.

Here are some of the predator communities you should be especially careful driving through, according to Strickland’s list: Carpinteria, Costa Mesa, Fullerton, Garden Grove, Hemet, Oceanside, Petaluma, Redlands, Ripon, Roseville, San Bernardino, Stockton, Tracy, Woodland — and dozens more.

They’re like speed traps. But there are no warning signs.

I called Carpinteria because that’s where I used to drive to the beach long ago. With the tax trap, I might not today. The city manager pleaded not guilty. It was the handiwork of the Carpinteria-Summerland Fire Protection District, he said.

The district fire chief, Mike Mingee, immediately corrected me about it being a crash tax. “We call it a fee for service,” he said.

The chief had a logical explanation for the fee: “We’re a small department that covers a large area of Highway101. A large percentage of auto accidents involve people just passing through. We’re trying to relieve the local tax burden and keep our heads above water.”

Good point, but it’s no justification for a screwy situation. The state should be funding accident response — fire safety — on the major highways, just as it does traffic enforcement. But the state doesn’t have enough money to buy a squirt gun.

Mingee added that the fee was imposed “in direct response to the state Legislature choosing to remove 8% of our [tax revenue] to balance the state budget in 2009.”

And he emphasized that the fee collector had been instructed only to bill insurance companies, not to pester motorists.

That won’t be the case in Sacramento, however. And unlike Carp, motorists here aren’t just passing through. Many thousands drive into town each day to work. Close to 500,000 live in the city (thankfully, I’m one). But nearly 600,000 more live elsewhere in the county, and they’re all potential victims of the crash tax, as well as people in bordering counties.

“Offensive” and “plain dumb,” Yolo County Supervisor Mike McGown called the crash tax. He asserted it proved what his neighbors on the west bank of the Sacramento River had always suspected: that the capital city looked down its nose at them and believed “West Sac was only good for whorehouses and truck stops.”

Great PR.

Sacramento Mayor Kevin Johnson, a homegrown former pro basketball star, has been standing firm behind the pending tax.

Here’s the fee schedule: $495 for a typical crash involving “scene stabilization,” $2,274 for a helicopter evacuation. Johnson estimates this will raise between $300,000 and $500,000 a year.

But not if out-of-towners boycott stores or cancel reservations.

Sacramento is a great place to live. But I wouldn’t want to visit.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.