‘Plastic’ lab confers a form of immortality

The first thing you notice upon entering the tidy white room is the pervasive smell of formaldehyde.

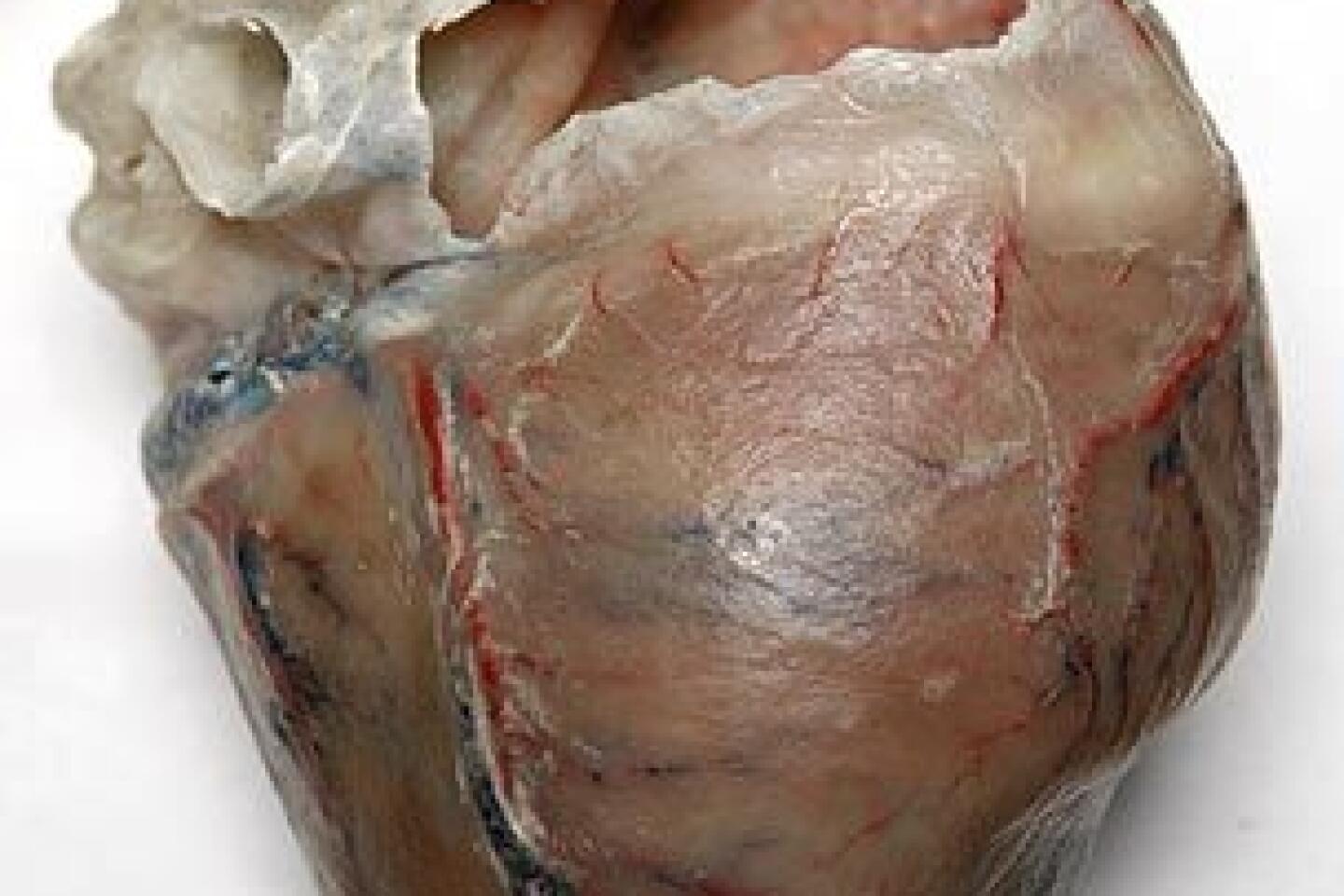

Then you see four people in lab coats cutting into an enormous, dripping elephant’s heart. A few feet away is a table strewed with a human head, feet and arms. And on a shelf nearby sits a large set of someone’s no-longer-functioning intestines.

Oh dear, you realize, it’s another day at Orange Coast College, full of learning and fun.

“How beautiful!” exclaims Ann T. Harmer as the grisly, pink 70-pound heart emerges halved from the Butcher Boy saw. “It’s going to be gorgeous.”

Thus passes an event that has become somewhat routine in this little corner of suburban Orange County: a new contribution by the college plastination lab to science and art.

Harmer, a professor of biological sciences at the Costa Mesa campus, founded the lab in 1994 with fellow professor Sharon Daniel after visiting a San Diego science facility to retrieve a cadaver.

“The curator showed us his plastination lab and we lost our minds,” the professor recalls. “It was the most amazing teaching tool we’d ever seen.”

Today, she believes, their creation is the granddaddy of all community college plastination labs.

The theory by which it operates is simple and well known: Replacing the water in a biological specimen with silicone polymer preserves it forever in something akin to plastic form. The process, invented by a German doctor in 1978 and used primarily on human bodies, has been made famous by exhibits such as “Body World 3,” currently at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

At OCC it is used to create educational exhibits for the college students and for paying customers, including museums, hospitals and other schools.

“It’s very artistic,” says Harmer, who has degrees in both science and art history. “If you are familiar with works of art, many of them depict the human body.

Early anatomists were also artists; they tried to represent the human body in ways that were educational but also pleasing to the eye.”

Of the estimated 1,000 specimens produced at OCC so far, she said, about 75% have been human bodies willed for the purpose. The rest include a variety of other species such as dogs, cats, rats, fetal pigs, fish, baby dolphins, sand sharks, an octopus and at least one enormous crab.

“We think of it all as art,” Harmer says.

The process begins with the body, which is preserved in formaldehyde until it can be dissected to the artist’s -- or client’s -- taste. It is then dipped into acetone, which replaces the water, and submerged in a polymer bath. Finally, the specimen is cured for up to six months to let everything dry.

“I think it’s incredible,” said Christine Todd, 31, a pre-med student who dreams of becoming a surgeon and likes to help out at the lab. “It’s an amazing way for students to learn; it’s great practice in sharpening your skills.”

On any given day, the lab is adorned with numerous examples of its work. The dainty arm on the table belonged to a 23-year-old woman who died of cystic fibrosis, Harmer explains. Nearby, under a velvet canopy of black and purple, is most of the rest of her body, cut into 48 horizontal slabs revealing her internal anatomy from head to lower torso.

“We call her Bernadette,” Harmer says, “because we thought she was a saint for contributing her body.”

Next to the arm is an elderly man’s head, also cut into slices. And placed neatly along a series of shelves are, among other things, several diseased kidneys and bladders, a pair of black smokers’ lungs, a few ruined human hearts and an alcoholic’s brain pocked deeply with scars.

“That’s why we like to bring students in here,” Harmer explains. “This is what your brain really looks like on drugs -- not a fried egg.”

In fact, she says, hundreds of people tour the lab each year, including elementary school children and retired senior citizens. At the core of the program, however, are the college students who perform much of the work and learn from their chores.

Among them is James Coopman, 23, a pre-nursing major who volunteers here part time and hopes to one day specialize in removing living organs from the bodies of donors who have died.

“This really helps,” he says, shortly after guiding the elephant’s big heart expertly through the saw.

Then he spreads the two halves open wide, proudly displaying the organ’s inner workings.

“It’s like flying an airplane,” Coopman explains. “You can learn from a book, but you don’t really know what it’s like until you get behind the wheel.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.