Daum: When parents hover

Since the release of the May 21 issue of Time magazine — the one with an attractive if rather indignant-looking young motherbreast-feeding a nearly 4-year-old child on the cover — much of the country has been abuzz with both admiration and condemnation of the child-rearing philosophy called “attachment parenting.” Known for its hyper-protectiveness, not to mention its plain-old hype, attachment parenting concerns itself with issues like the benefits of home schooling, the value of “co-sleeping” and whether disposable diapers and store-bought baby food are instruments of neglect.

Then last week came parenting news of a very different kind. A man named Pedro Hernandez had confessed to killing Etan Patz, the 6-year-old who, in 1979, was allowed to walk two blocks to the bus stop in his Manhattan neighborhood and was never seen again.

I’d like to think that upon hearing this news, people stopped bickering about Huggies versus hemp, if only for a moment, and recognized that worse things can happen to a child than being swaddled in non-organic fabric. To put it mildly, Hernandez’s sick-making description of strangling the boy in the basement of a bodega, wrapping the body in a garbage bag and then tossing it in the trash — though it has still not been proved true — invites some reflection about the value of not sweating the small stuff.

Ironically, it may well have been 33 years ago, amid the roiling panic of the Patz case, that some of the seeds of the attachment parenting movement were planted. As those of us old enough to remember the case know all too well, Patz’s sweet, artfully photographed face represented more than just the first missing child to appear on a milk carton. It represented a shortening of the leash for children everywhere.

And not without some reason. The year of Patz’s disappearance marked the beginning of a string of child and adolescent murders in Atlanta that would terrify and transfix the nation for two years; then the much-publicized kidnapping and murder of 6-year-old Adam Walsh from a store in Florida seemed to pick up where the Atlanta nightmare left off. In 1983, President Reagan declared May 25, the day of Patz’s disappearance,National Missing Children’s Day.

Throughout all this, children were taught about “stranger danger.” Free-roaming outdoor play was slowly eclipsed by closely monitored structured activity. Walking to the library or bike riding to a friend’s house were replaced by parental chauffeuring. Moreover, the choice to raise kids in the city, particularly one as troubled as 1970s-era New York, was regarded with suspicion. In the sleepy New Jersey suburb where I spent the latter part of my childhood, I recall overhearing a conversation about the Patz case wherein, in a desperate grab for reassurance that the same fate wouldn’t befall her family, another mother said to my mother, “You have to wonder if they brought this on themselves. After all, they live in Soho — in a loft.”

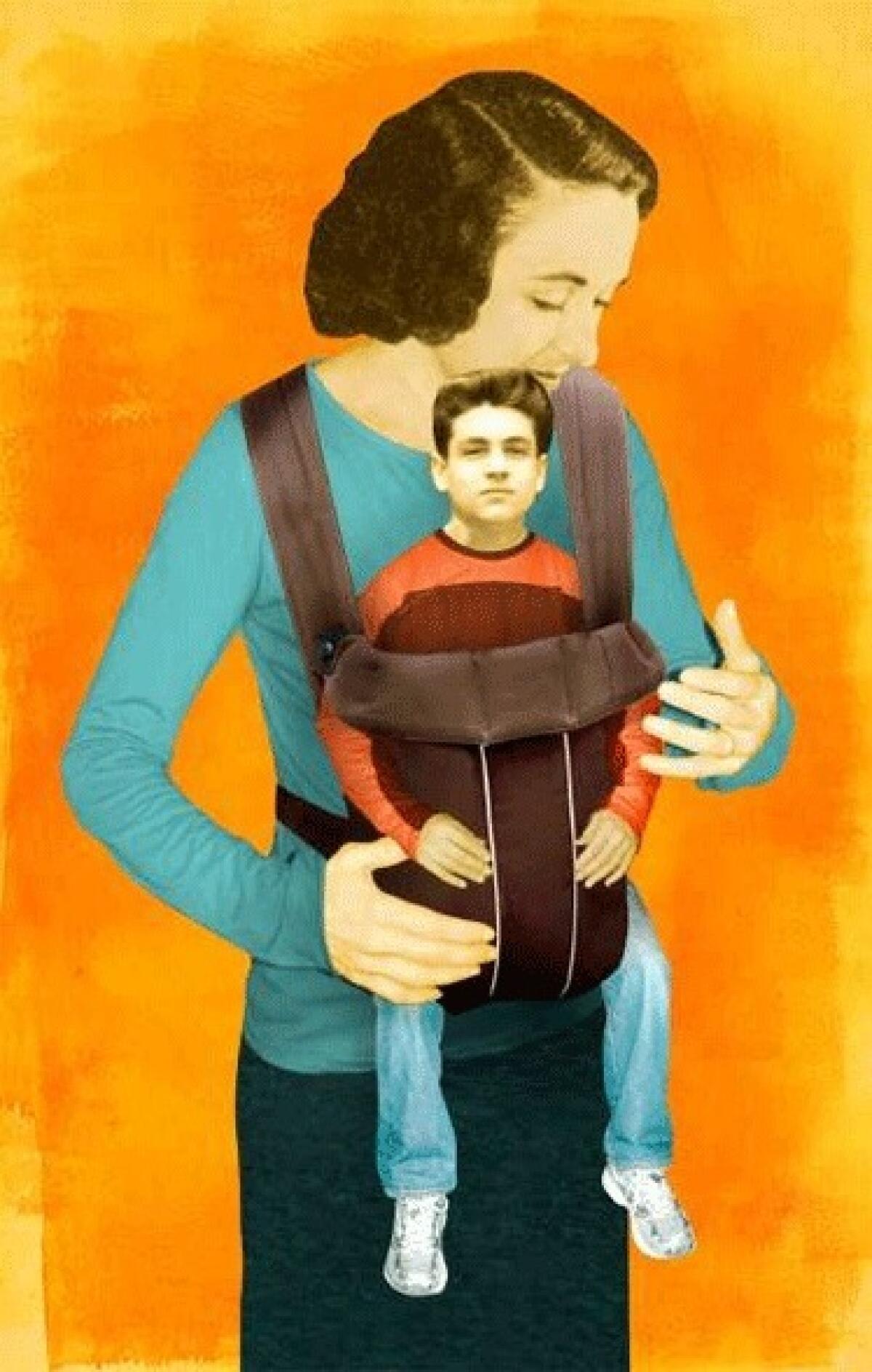

Now places like Soho are epicenters for the hovering “helicopter parents” (who in some cases are so rich they also commute to work by helicopter) who have sheltered and micromanaged their children into near-helplessness. But it’s worth noting that every generation worries about its children in its own way — and, in most cases, more than it needs to. An oft-cited figure when it comes to missing children is that 800,000 are reported each year. What that number belies, however, is that the definition of “missing child” includes runaways and children abducted by a parent. Research from the Department of Justice puts “stereotypical” kidnappings at just over 100 per year — an unsettling number but hardly a national scourge.

What happened to Etan Patz, in other words, is incredibly rare. Sure, it could be presented to the public as part of a nefarious and growing trend, as the latest reason that society is going to hell. But, like mothers in the industrialized world who breast-feed 4-year-olds, what happened was the exception: Most kids don’t disappear, and when they do, not that way.

That’s important to remember as we are, once again, being instructed to be scared for the nation’s children. This time, the boogeyman isn’t a mostly nonexistent marauder who strikes when parents aren’t looking. It’s the ever-lurking, overbearing parents themselves.