Research sparks debate on popular type of stroke therapy

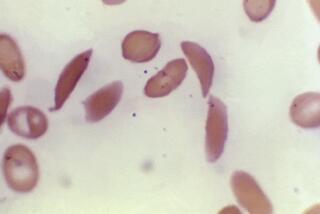

New research is raising doubts about a popular form of stroke therapy that aims to snatch a blood clot from a patient’s brain and restore vital blood flow before serious damage is done.

In clinical trials presented this week at the American Heart Assn.’s International Stroke Conference, researchers found that use of these devices did not improve health outcomes for stroke patients who made it to the hospital in time to use a clot-busting medication called tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA.

The devices, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2005, have taken the stroke community by storm and are widely used in stroke centers across the country to clear clots that have cut off blood to the brain. But the trial results suggest that, for the earliest generation of the devices at least, the benefits of retrieving clots through blood vessels have been overstated.

The studies, which were also published online by the New England Journal of Medicine, touched off a flurry of debate among neurologists, vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who have embraced the mechanical clot retrieval systems despite conflicting evidence of their benefits.

The largest of the clinical trials compared outcomes in stroke patients who were randomly assigned to receive either tPA alone or tPA along with the endovascular therapy. That trial, conducted in 58 hospitals in the U.S., Canada, Australia and Europe, was halted ahead of schedule after safety watchdogs concluded the invasive devices offered no benefit but did present small risks.

The 434 patients who were treated with endovascular therapy were just as likely to die and to be disabled three months after their strokes — and were no less likely to suffer bleeding in the brain — compared with the patients who got tPA alone. Patients treated with the devices were more likely to experience bleeding in their brains, though it wasn’t bad enough to cause symptoms.

The results were published Thursday.

The findings represent “one of the most significant announcements in stroke in the past five years,” said Dr. Patrick D. Lyden, chairman of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

A smaller randomized clinical trial involving 362 patients in Italy had similar results. Those findings were published Wednesday.

The arrival of clot-retrieval devices was widely hailed as a new era in stroke care, Lyden said.

“In meeting after meeting, picture after picture, we’d see that ‘Here’s a blocked artery. Here comes the retrieval device. Now it’s open,’” he said. “How could that not work?”

The device-driven therapy has also become a major source of revenue and prestige for hospitals that offer it. Stroke care that uses a retrieval device typically costs close to $25,000 — about twice as much as the use of tPA alone.

Offering the more invasive treatment as an adjunct to the clot-busting drug “is perfectly ethical when we don’t know better,” Lyden said. With the new findings in hand, however, “we need to take a very careful look at who’s going to get these procedures,” he said.

But Dr. Reza Jahan, an interventional neuroradiologist at UCLA who had a hand in inventing the first clot-retrieval devices, said it would be premature to dismiss the value of endovascular therapy on the basis of the new studies.

The devices used in both trials — mainly the Merci Retrieval System — have been superseded by a newer generation of devices, two of which have been shown to clear clot-blocked arteries in the brain faster and more completely.

Newer devices, including the Solitaire Revascularization Device and another marketed as the Trevo device, are designed to remove a blood clot and insert a stent to keep the artery open. The stent is often coated with a drug to prevent further clots from forming.

“Physicians truly believe in these procedures because of the spectacular reopening of a clogged artery they see,” Jahan said. “And most people think that a reopened artery is equal to a good outcome.”

But the new trial results call into question the presumption that physically opening blocked arteries to the brain will always reduce the devastating impact of a stroke, he acknowledged.

“The new devices do work better,” he said. “Whether that will translate into improvement in outcomes at three months is not known, and the only way to test efficacy is by doing a controlled trial.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.