WHERE THE FAULT MEETS THE SALT: Exploring the most dangerous line in La Jolla

The tour guide stops his line of cyclists, instructing them to walk their rented bicycles north across the Coast Walk Trail Bridge instead of riding them.

“How many of you have crossed an active earthquake fault before?” he asks as no hands go up. “Well, you’re about to now.”

The Light has come to this spot to learn more about the Rose Canyon Fault from an expert. Paleoseismologist Drake Singleton is a doctoral student specializing in this very seismic feature for a dual degree from UC San Diego and San Diego State University. Last year, Singleton and his team dug a 160-foot-long, 3-foot-wide trench into the fault beneath the Presidio Hills Golf Course, spending months analyzing the sediment for proof of past quakes.

Before 1990, the Rose Canyon Fault was thought to be inactive, giving San Diegans a false sense of seismic security. What Singleton’s work proved was great news for science, but not necessarily for La Jollans: Big ones happen every 750 years, about twice as frequently as thought.

“The west side of this fault line is moving northward, and the east is moving southward — just like the San Andreas,” Singleton says, explaining that both faults result from the Pacific crustal plate sliding past the North American plate, inching all of coastal California northward as the mainland stays put.

“If we stood here for many millions of years, we would see La Jolla Cove move northward and La Jolla Shores and UCSD move southward,” he says.

Singleton explains this mind-blowing concept while pointing to photos he just snapped with a cell-phone camera. The plan was for him to point to the actual fault line — which marks where two sandstone formations slide against one another — during this interview, not to photos. However, an hour earlier, he and this reporter attempted to get to the isolated Matlahuayl State Marine Reserve beach by foot, through the low tide coming from The Marine Room. (Singleton charted when the water would be the shallowest.)

But four-foot waves splashed our unprotected electronics, forcing us to turn back and prompting Singleton to suggest dropping down from underneath the Coast Walk Bridge.

“It’s not a difficult climb,” he said, which was a horrible, horrible lie.

The 50-foot plummet used to be called “Devil’s Slide” in 1930s, when visitors were lowered by rope down a narrow footbridge to look inside the dark caves on the cliff. (Before that, in the 1890s, it was known as “Dead Man’s Leap,” when local daredevil “Professor” Horace Poole leaped regularly from the top.)

So Singleton made the 80-degree descent himself — without a footbridge, ropes, or this reporter — coming back up with blurry photos taken too close to provide context. (Singleton is not quite to photography what he is to paleoseismology.) Fortunately, La Jolla Kayak allowed the Light to use a photo of the fault from its website, taken from the ideal vantage point for this formation — the ocean.

It’s our own fault

La Jolla plays an important part in the Rose Canyon Fault story since it is in this spot that the fault disappears offshore for 84 miles, not making landfall again until Newport Beach.

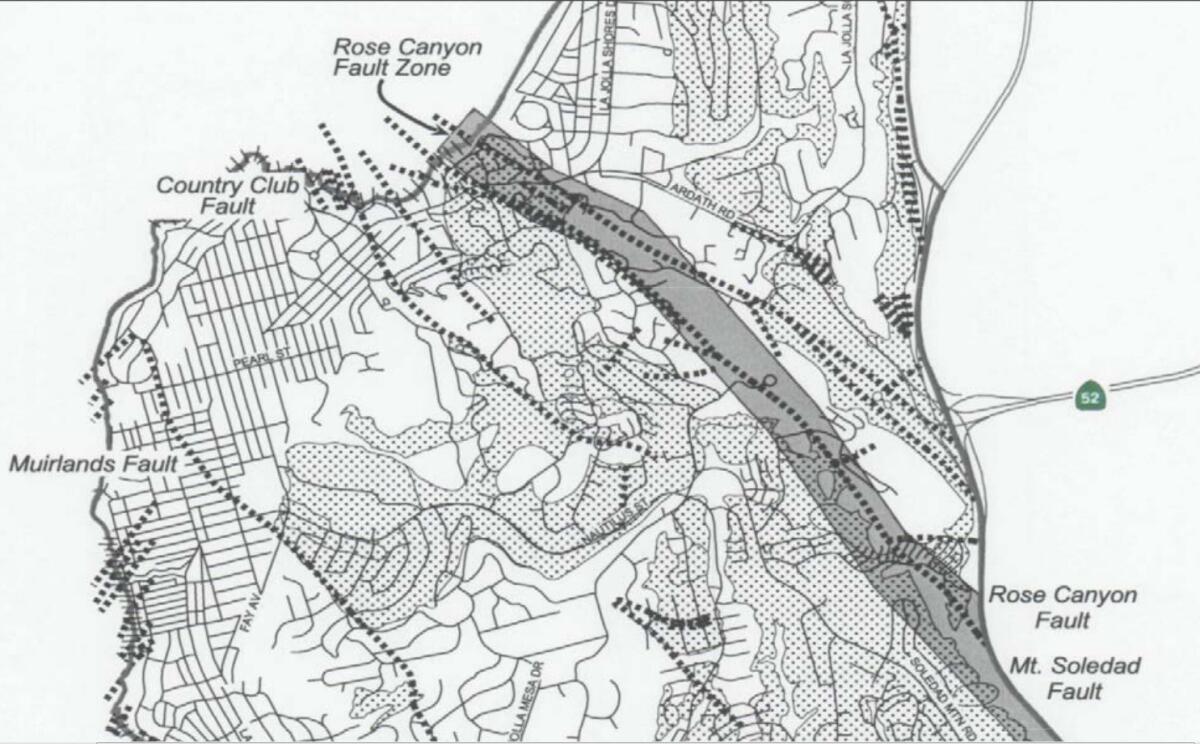

Well, not exactly, Singleton corrects one of several misconceptions expressed by this reporter. Rose Canyon is a fault system, not a single fault line. It consists of three main segments in La Jolla. The one we’re on top of now is called the Country Club segment, since it runs just north of the fairway. The Mt. Soledad and Rose Canyon segments lay north of us. They pretty much take the I-5 from downtown, suddenly veer left, then run adjacent to La Jolla Parkway to Torrey Pines Road and drop into the ocean — one most likely beneath the La Jolla Beach & Tennis Club, the other most likely beneath the Marine Room.

Since any potential surface evidence of their existence has been long since paved over, the Country Club fault is the only one still visible, but all three are equally powerful. They all join up offshore, where the single fault hugs the continental shelf in a roughly straight line three-to-four miles out.

Also, to be technically correct, the Rose Canyon Fault has been considered merely a segment of the Newport-Inglewood-Rose Canyon Fault since last year, when Scripps Institution of Oceanography announced that the two faults, previously thought to be separate, are connected offshore and could produce large earthquakes together.

Lifting La Jolla

“It’s still a very small fault compared to the San Andreas,” Singleton says, “and that’s actually a very good thing.”

Even the seismic activity on a small fault can have an impact the size of Mt. Soledad. In fact, that’s exactly the impact that the Rose Canyon has had. As Singleton explains: “It created Mt. Soledad.”

Rose Canyon is a strike-slip fault, which means it moves crustal blocks horizontally, preferably in nice, straight lines. When those two aforementioned segments suddenly veered left, Singleton explains, this created a barrier to slippage at which they locked up and pressure began building. Slowly, the vertical release of that pressure lifted — by a meter or two with each earthquake over eons — some Cretaceous-era seabed and Eocene-era river deposits 823 feet straight up into the air and into an eventual home for development millionaires, Munchkin myths and Dr. Seuss.

In addition to creating Mt. Soledad, the Rose Canyon Fault created La Jolla Cove, since all that lifting also forced more land outward to sea than anywhere else in San Diego. (Farther south, the Rose Canyon Fault depressed the ground below sea level to create San Diego’s two bays.)

La Jolla destroyer?

Pressure on the Rose Canyon Fault hasn’t subsided at all in the 4 million years since it began. Rather, Singleton says, “it’s been steady.” The fact that we can’t feel earthquakes now just means the pressure is building up for future release.

The next time the fault ruptures completely, according to Singleton, it could unleash between a Magnitude 6 to 7 quake, potentially causing between 1 and 1.5 meters of slippage. According to a 2017 study sponsored by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, such an earthquake could kill 2,000 people and inflict $40 billion in property damage.

Singleton points out that this study was met with some criticism from the earthquake community. He prefers to describe such an earthquake merely as producing “intense shaking and possible freeway closures.” Furthermore, he says that buildings built to earthquake code should remain standing. (Residential projects proposed within the Rose Canyon Fault zone are required to undergo a comprehensive geotechnical analysis and geological report before the City will issue building permits.)

So how long do we have before discovering who’s right?

Singleton says the last “big one” struck between 1700 and 1769 — still relatively recently in a 750-year cycle — so the potential for a large earthquake on the Rose Canyon Fault in the next 450 or so years is small.

Unless, of course, he’s wrong.

“We are likely not wrong about when the last earthquake happened,” he replies, “but there is no way of knowing when the next earthquake will occur on any given fault.”

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.