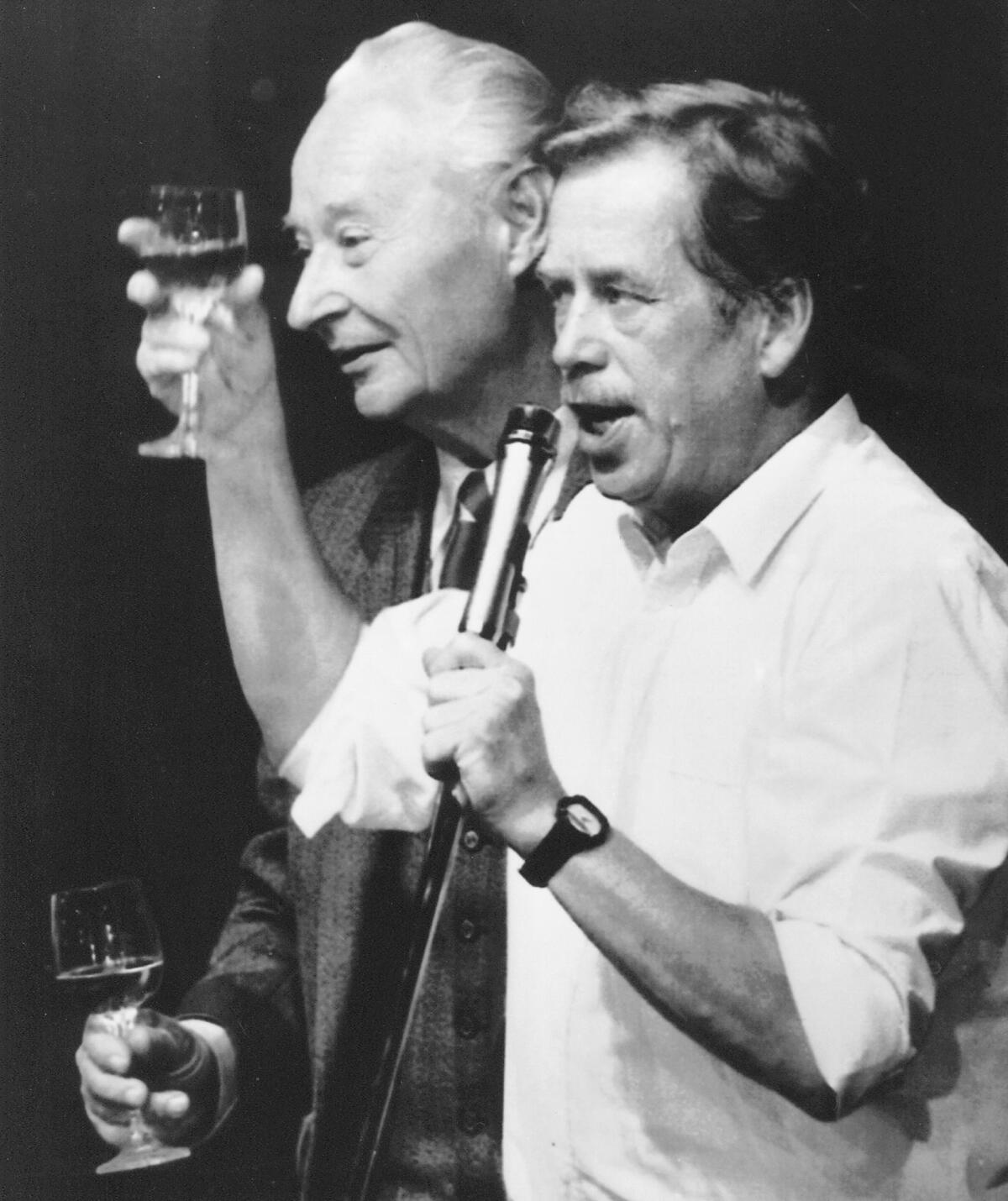

Vaclav Havel dies at 75; Czech leader of ’89 ‘Velvet Revolution’

Vaclav Havel, the former dissident playwright who led Czechoslovakia’s 1989 “Velvet Revolution” against communism and then served as his country’s president, died Sunday. He was 75.

Havel, a former chain smoker with chronic respiratory problems, had been in failing health the past few months and died at his weekend home in Hradecek in the northern Czech Republic, his assistant, Sabina Tancevova, told the Associated Press.

World leaders mourned his death. Lech Walesa, the former Polish president and Solidarity movement founder, called Havel “a great fighter for the freedom of nations and for democracy” whose “voice of wisdom will be missed.” President Obama said Havel “helped unleash tides of history that led to a united and democratic Europe.”

PHOTOS: Vaclav Havel, 1936-2011

Of all the heroes of the anti-Communist struggles in Eastern Europe, Havel most successfully navigated the political challenges of democracy and free markets, remaining at the peak of political influence for more than a decade. He was president of Czechoslovakia from December 1989 until July 1992. After the nation split in two and Slovakia went its own way, he served as president of the Czech Republic from 1993 until 2003, just months before the two nations joined the European Union.

Romantic idealism, often expressed in deep philosophical terms, colored his career, whether he was ridiculing communism in his plays or searching for the meaning of life during his time in prison as well as during his presidency.

“The [Communist] past has left us spiritually impoverished,” he declared in pledging as president to focus on “the ethical, moral aspects of society, on creating space for dialogue, agreement and tolerance.”

As a dissident leader, Havel promoted the slogan, “May truth and love triumph over lies and hatred.” During his years in office he stressed the importance of “civil society,” or citizens’ organizations free of government control, as the underpinning for democracy.

“None of us—as an individual—can save the world as a whole, but . . . each of us must behave as though it were in his power to do so,” Havel wrote in his 1997 book, “The Art of the Impossible: Politics as Morality in Practice.”

As president, Havel sought to guide his country away from its Communist past while avoiding witch hunts against former rulers.

“The transformation of the totalitarian system into a democratic one is not only a matter of several parties replacing one ruling party and the introduction of some democratic mechanisms,” Havel said in a 1994 interview with The Times. “It is also a matter of a great transformation of thinking because people must learn again to be citizens, to rediscover the civic responsibility which the totalitarian regime did not demand from them because it required mere obedience.”

Havel presided over Czechoslovakia’s transition to democracy and a market economy, the 1991 withdrawal of Soviet troops and the Czech Republic’s 1999 entry into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which ensured its status in the mainstream of Western institutions. He was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, received numerous honorary doctorates and was awarded various international honors for his human rights efforts, including the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush, who hailed him as “one of liberty’s great heroes.”

“The demons that have so fatally tormented European history—most disastrously of all in the 20th century—are merely biding their time,” Havel once warned, stressing that Europe’s prosperous West and formerly Communist East must seek unity. “Just as one-half of a room cannot remain forever warm while the other half is cold, it is equally unthinkable that two different Europes could forever live side by side without detriment to both.”

Havel’s popularity at home gradually faded from levels accorded a national hero to those of an ordinary politician. “President Havel walks a sad road, from a politician who is a favorite, who is admired, sometimes even idolized, to a politician who is misunderstood, rejected and sometimes even condemned and damned,” the newspaper Mlada Fronta Dnes noted in a 1999 commentary, when polls showed his support had fallen to about 50%, compared with ratings as high as 80% earlier in the decade.

Yet Havel’s global status as a voice for democracy and morality in government remained undiminished.

He was born Oct. 5, 1936, into a Prague family of entrepreneurs, real estate developers and philanthropists. His early years were marked by privilege, but his family’s prosperity made it a target after the Communists seized power in 1948.

Havel was ruled ineligible for secondary education because of his “bourgeois background” and had to finish his diploma at night school while working days. He later was denied entry to the history and philosophy departments of Prague’s prestigious Charles University; he studied economics at a technical institute instead.

His frustrations became a source of creativity, as he mocked the Communist system’s bureaucratic foibles and obfuscating jargon in his starkly modern and often absurdist plays, which included “Beggar’s Opera,” “The Garden Party,” “Audience,” “Largo Desolato,” “Temptation” and “The Memorandum.”

After the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia crushed that year’s “Prague Spring” reform effort, Havel became firmly convinced of the long-term political importance of moral resistance to dictatorship. An increasingly prominent pro-democracy leader and critic of the Soviet-installed regime, he was soon charged with activities against the state. His plays were banned and it was forbidden even to publish his photograph.

In 1975, he released a famous denunciatory essay in the form of an open letter to Gustav Husak, the country’s hard-line president. “True enough the country is calm,” he wrote to Husak. “Calm as a morgue or a grave, would you not say?”

Two years later, after members of a punk band called the Plastic People of the Universe were arrested on charges of “disturbing the peace,” Havel helped organize the signing of the so-called Charter 77 by writers, actors and various intellectuals demanding basic human and civic rights. That move triggered a revival of dissident activity after nearly a decade of repression so severe that almost no opposition had been visible.

Havel was arrested in January 1978 and spent a nearly five years in jails and a labor camp. Each of his terms in prison triggered a wave of protests. Letters he wrote from prison to his then-wife Olga, whom he had married in 1964, were later published in a famous collection that reflected both the love and the friction in their marriage, which lasted until her death in 1996 from cancer.

In early 1989 Havel was jailed again for several months, but by November the Communist regime began to falter. A Nov. 17, 1989, student demonstration was crushed with brutal police measures that triggered a wave of public outrage. A few days later, Havel held a news conference in his living room to announce the formation of Civic Forum. It organized further huge protests and held talks with the crumbling Communist government, successfully persuading it to relinquish power.

During the decisive protests, crowds often shouted “Havel to the Castle,” a reference to the presidential residence in Hradcany Castle, perched on a Prague hilltop. One of the Communist-dominated parliament’s last acts was to agree to do just that, as it elected Havel president in December 1989.

Havel’s political triumphs were still to be paired with one great defeat: his inability to keep Czechoslovakia united. He argued strenuously against the breakup and pushed hard for a nationwide referendum that most people believed would have shown support for maintaining a single country. But differences between the leading Czech and Slovak political parties over the pace of economic reforms, combined with festering Slovak resentment against Czech domination of the country, proved too much to overcome.

He resigned as president in July 1992. The country split on Jan. 1, 1993.

Critics later said that Havel bore some of the responsibility for the breakup because he had failed to take stronger action earlier in his presidency to address Slovak concerns.

Havel was elected president of the Czech Republic on Jan. 26, 1993. His popularity at home peaked in late 1996, when he underwent surgery for removal of a cancerous tumor and part of a lung, provoking a massive outpouring of sympathy.

But his luster was soon tarnished, in the eyes of some, when he emerged from the hospital in January 1997 to marry actress Dagmar Veskrnova. To many Czechs, she did not measure up to his widely admired first wife. The next year, he had two more brushes with death, from a ruptured colon and from pneumonia.

Havel, who quit smoking after his lung operation, was plagued during the later years of his presidency by repeated hospitalizations for lung infections, which often interfered with his official duties. Some critics felt he was no longer physically up to the job and was becoming isolated from ordinary people.

His loyal supporters argued that the new mood primarily reflected public disenchantment with all politicians after the turbulence of a decade of dramatic change.

Havel was philosophical about the criticism he faced toward the end of his time in office. “I have been so long at the head of state . . . and for so long I was an object of almost uncritical homage,” he said. “This had to be broken eventually.”

He remained an emblem for the world and a strong voice of modern Europe.

He also returned, in 2008, to the stage, debuting a new play that evoked personal struggles. Called “Leaving,” it focuses on a leader grappling with an uncertain future as he leaves office. It won critical praise.

When the play was published, he was asked by an interviewer whether he wanted to be remembered as a politician or a playwright. “I would like to say,” he said, “that [he] was a playwright who acted as a citizen, and thanks to that he later spent a part of his life in a political position.”

PHOTOS: Vaclav Havel, 1936-2011

Holley is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.