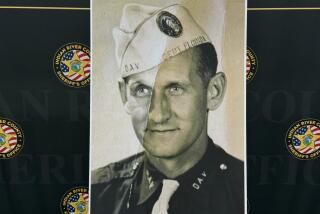

Albert Brown dies at 105; oldest survivor of Bataan Death March

A doctor once told Albert Brown he shouldn’t expect to make it to 50, given the toll taken by his years in a Japanese labor camp during World War II and the infamous, death-filled march that got him there. But the former dentist made it to 105, embodying the power of a positive spirit in the face of inordinate odds.

FOR THE RECORD: An earlier headline with this article described Albert Brown as the last survivor of the Bataan Death March. He was believed to be the oldest survivor.

“Doc” Brown was nearly 40 in 1942 when he endured the Bataan Death March, a harrowing 65-mile trek in which 78,000 prisoners of war were forced to walk from Bataan province near the Philippine capital of Manila to a Japanese POW camp. As many as 11,000 died along the way. Many were denied food, water and medical care, and those who stumbled or fell during the scorching journey through jungles were stabbed, shot or beheaded.

But Brown survived and secretly documented it all, using a nub of a pencil to scrawl details into a tiny tablet he concealed in the lining of his canvas bag. He often wondered why captives so much younger and stronger perished while he went on.

By the time he died Sunday at a nursing home in Nashville, Ill., Brown’s story was well-chronicled, by one author’s account offering an encouraging road map for veterans recovering from their own wounds in many wars.

“Doc’s story had as much relevance for today’s wounded warriors as it did for the veterans of his own era,” said Kevin Moore, co-author of the recently released “Forsaken Heroes of the Pacific War: One Man’s True Story,” which details Brown’s experience.

Brown, recognized in 2007 at an annual convention of Bataan survivors as the oldest one still living, couldn’t muster the strength to talk about his experiences until about 15 or so years ago, his family said.

His account described the torment that the marchers experienced as they passed wells U.S. troops had dug for natives but weren’t allowed to drink from once they became prisoners. Filipinos who tried to throw fruit to the marchers frequently were killed.

Brown remained in a POW camp from early 1942 until mid-September 1945, living solely on rice. The once-athletic man saw his weight wither by some 80 pounds to less than 100 by the time he was freed. Lice and disease were rampant.

Born in 1905 in North Platte, Neb., Brown moved with his family to Council Bluffs, Iowa, after his father, a railroad engineer, died when a locomotive engine exploded.

He studied dentistry at Creighton University in the 1920s and was called to active duty in 1937, leaving behind a wife, children and a decade-old dental practice that his war injuries prevented him from resuming.

By the time the war ended in 1945, the 40-year-old Brown was nearly blind, had weathered a broken back and neck and suffered through more than a dozen diseases including malaria, dysentery and dengue fever.

He took two years to mend, and a doctor told him to enjoy the next few years because he had been so decimated he would be dead by 50. But Brown soldiered on, living in Los Angeles for a time before moving to southern Illinois.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.