Bruce Surtees dies at 74; cinematographer worked with Eastwood and Fosse

Early in his career as one of Hollywood’s top cinematographers, Bruce Surtees became known for his artful use of low-level, moody lighting in films such as Don Siegel’s “The Beguiled” and “Dirty Harry” and Bob Fosse’s “Lenny.”

Surtees, 74, who received an Oscar nomination for his work on “Lenny” and was closely associated with Clint Eastwood on many of his films, died Feb. 23 in Carmel, Calif., of complications of diabetes, said his wife, Carol.

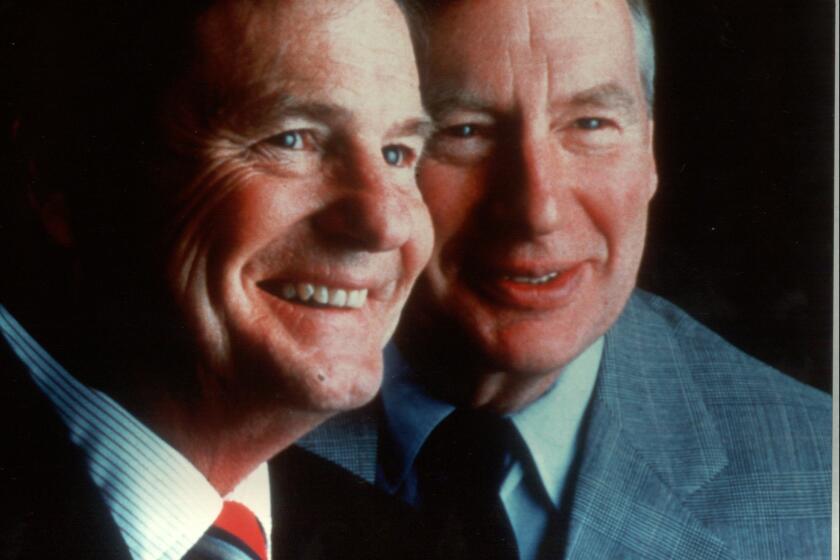

FOR THE RECORD:

Bruce Surtees: In the March 2 LATExtra section, a photo accompanying the obituary of cinematographer Bruce Surtees was described by the source, Getty Images, as showing him with Clint Eastwood during filming of “High Plains Drifter.” In fact, the man pictured with Eastwood was assistant director Jim Fargo.

The son of three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer Robert Surtees, Surtees launched his career working for his father as a camera assistant on the 1965 western “The Hallelujah Trail.”

He had been the camera operator on two Siegel-directed Eastwood films made by Eastwood’s production company — “Coogan’s Bluff” (1968) and “Two Mules for Sister Sara” (1970) — when he made his debut as a director of photography on Siegel’s 1971 Civil War drama “The Beguiled,” also starring Eastwood.

Eastwood then chose Surtees to be the director of photography on “Play Misty for Me,” his 1971 feature film debut as a director.

Surtees went on to be the director of photography on six other Eastwood-directed films over the next decade and a half, “High Plains Drifter,” “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” “Firefox,” “Honkytonk Man,” “Sudden Impact” and “Pale Rider.”

“He was very creative; he had good thoughts and ideas,” Eastwood told The Times on Thursday, noting that “he wasn’t afraid to take chances in shooting with low-light contrast. He was always looking to improve shots, and he could do a lot with little equipment in a very short time. He was able to make things happen.”

Eastwood recalled that while making “Coogan’s Bluff” in New York, Surtees sat behind him with a hand-held camera as Eastwood raced a Triumph motorcycle through Fort Tryon Park.

“So he was kind of fearless, or at least he put a lot of faith in the fact I could ride this damn thing,” said Eastwood. “Then we’d turn around and have him ride backward on the motorcycle, and he’d be shooting the guy chasing me. He was just willing to try anything to get a shot.”

“Lenny,” a movie about comedian Lenny Bruce shot in black and white and starring Dustin Hoffman, earned Surtees his nomination for best cinematography in 1975.

In his review of the film, The Times’ Charles Champlin said that Fosse and Surtees “beautifully catch the flat neon world of all-night cafeterias, the smoky squalor of strip joints and coffee houses, the gray anonymity of hotel rooms and cheap apartments. As in ‘Cabaret,’ atmosphere becomes the shaping force on character that it is.”

“He was a rare Hollywood cinematographer who had no fear of exploring deep and profound blacks on screen,” said Tom Stern, a cinematographer who works frequently with Eastwood and previously worked with Surtees as a lighting technician on many films.

“He wasn’t afraid of having the character exist in either silhouette or total darkness and letting the dialogue do the work,” Stern said. “He enjoyed existing outside of the mainstream, but in my opinion he gave a lot of us fellow cinematographers permission to go into previously forbidden areas of darkness.”

Surtees was director of photography on two other Siegel films starring Eastwood — “Dirty Harry” (1971) and “Escape From Alcatraz” (1979) — and on Siegel’s “The Shootist” (1976), starring John Wayne.

The director was a big fan of Surtees’ work.

In Stuart M. Kaminsky’s 1974 book “Don Siegel: Director,” Siegel recalled wanting to get a shot in darkness illuminated by a single candle for “The Beguiled.”

“The old way to get a picture of someone walking with a candle was to set up a complicated series of controlled lights, dimmers, clicking on, synchronized to the step of the person with the candle,” Siegel said. “I didn’t want that kind of thing again. So I picked young Bruce Surtees, and said, ‘You’ve got to do it without dimmers.’ If I’d said that to an old-timer, he would have said goodbye.”

For the scene, Siegel said, Surtees “put a little bulb in the base of the candleholder and we shot. It took guts.

“When we saw the film, most of the screen was black except for a circle of light showing the girl’s face. We didn’t care that it was black, that it wouldn’t show up on a television screen when the studio sold the picture to some network in a couple of years. Screw them. We liked it. It was exciting.”

Stern, who received an Oscar nomination for his cinematography on the 2008 Eastwood-directed film “Changeling,” described Surtees as a “gentle and joyful man.”

“He was a very important mentor to me, and I always appreciated his almost childlike freshness in his approach to every situation,” Stern said.

Among Surtees’ other movie credits as director of photography are “Joe Kidd,” “Blume in Love,” “Night Moves,” “Leadbelly,” “Big Wednesday,” “Risky Business,” “Tightrope” and “Beverly Hills Cop.”

He also received an Emmy nomination in 1999 for his cinematography for the A&E biographical drama “Dash and Lilly.”

Surtees, whose father won Oscars in the 1950s for “King Solomon’s Mines,” “The Bad and the Beautiful” and “Ben-Hur,” was born in Los Angeles on Aug. 3, 1937.

He studied at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and worked as a technician in the animation department at Disney Studios before becoming a camera assistant for his father.

In addition to Carol, his wife of 32 years, he is survived by a daughter from a first marriage that ended in divorce, Suzanne Surtees; his brother, Tom; and his sister, Nancy.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.