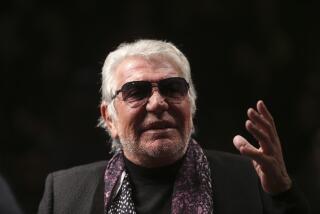

Charles Lisanby dies at 89; Emmy-winning production designer

Emmy-Award winning production designer Charles Lisanby, known for his lavish sets during the golden age of TV variety specials, died Aug. 23 in Los Angeles. He was 89.

According to his longtime agent and manager, Bob Goodman, Lisanby had recently fallen. The cause of death, according to Morgan’s Funeral Home, was sepsis.

Lisanby created huge, meticulous sets for specials starring Barry Manilow, Diana Ross and many others, as well as for an Oscars show and ice show telecasts. But he was a cultured world traveler who drove his assistants and crews to distraction not only for his attention to detail but also for insisting on listening to opera broadcasts as they worked.

He was also known in art circles for his close relationship with Andy Warhol in New York before their careers took different paths.

“He was not just someone born and raised on TV,” said producer-director Steve Binder, who worked with Lisanby on several shows, including the 1988 “Barry Manilow: Big Fun on Swing Street” that earned Lisanby one of his three Emmys for art direction. “He had theatrical experience, opera, worked in Radio City Music Hall.”

At the beginning of a project, Binder said, he would want to hear Lisanby’s ideas for the set instead of expressing his own.

“With Charles,” Binder said, “I would be the one asking him, ‘Pitch me.’”

Lisanby worked in a wide range of styles, from simple, abstract designs to elaborate re-creations of famed locales such as the Palace of Versailles.

Asked in a 2007 taped interview for the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences to characterize his design style, Lisanby said that would be difficult to do. “The set always has to tell a story,” he finally said. “It always has to further what the subject is.”

Charles Alvin Lisanby Jr. was born Jan. 22, 1924, on a farm outside Princeton, Ky.

From the time he was a child, he was creating theatrical sets. “I used to listen to the opera every Saturday afternoon, broadcast from the Metropolitan,” he said in the 2007 interview. “While listening to it, I would design the set and make it out of paper.”

After a stint in the Army cut short by a bout of meningitis, he landed in New York City in the late 1940s. One of his jobs was to paint murals, including at the famed Friars Club, where show business people gathered.

His work there was seen by a CBS director, Ralph Levy, who asked Lisanby to create a set for an experimental 1948 TV broadcast of the ballet “Billy the Kid” set to Aaron Copland’s music. The setting he sketched was purposely spare to suggest Old-West surroundings, and Lisanby hounded network carpenters to stop “improving” the set to make it look more realistic.

His work was a hit with network brass, which led to assignments on such programs as “The Garry Moore Show.” That live, weekly show included musical numbers with humorous sets that influenced a generation of future designers.

“I remember as a kid seeing one set that was a log cabin, and suddenly the walls spun around and it became a castle,” said designer Dwight Jackson, who later won an Emmy of his own. “To me the transformation seemed magical. And they were doing this show live, every week.”

Lisanby also took jobs on stage productions to work with legendary designers such as Cecil Beaton and Oliver Messel.

He met Warhol at a party in the mid-1950s, long before the artist became famous. They often sketched together and in 1956 took a seven-week trip around the world, studying art and culture in Asia and Europe.

Lisanby characterized the relationship as best friends, but according to Matt Wrbican, chief archivist of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Warhol wanted it to be much more.

“Andy was very much infatuated with Charles,” Wrbican said, and made numerous drawings of Lisanby. But although the designer was also gay, the romantic feelings were not mutual. “As far as we know, it was completely unrequited,” Wrbican said.

In the 2007 interview, Lisanby said the relationship cooled after the trip. “He realized I was never going to come live with him.”

Lisanby moved to Los Angeles, where he worked on “The Red Skelton Hour” and specials. Although he was somewhat pigeon-holed as a designer of musical shows, he won the job of designing sets for the 1974 multi-part “Benjamin Franklin” historical series. It won him his first Emmy.

He won another Emmy for the 1980 special “Baryshnikov on Broadway” that featured a tall, abstract rendering of a theater backstage, all painted white. It made a big impression on designer John Shaffner, who went on to win several Emmys and become chairman of the television academy.

“Charles was never afraid to make [a set] go all the way to the ceiling,” Shaffner said. “A lot of us get chicken at 14 feet, but he was like, ‘No, let’s go all the way — they’ll figure out how to light it.’”

Lisanby’s last major TV credits were in the 1990s, but by then he was also designing huge sets for holiday spectacles staged at the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove.

In 2010 he was inducted as the only production designer in the television academy’s Hall of Fame.

Lisanby was buried in Princeton, not far from where he grew up. He is survived by his life partner, retired costume designer Richard Bostard.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.